How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

13 Words, Words, WORDS!

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

Words, Words, WORDS!

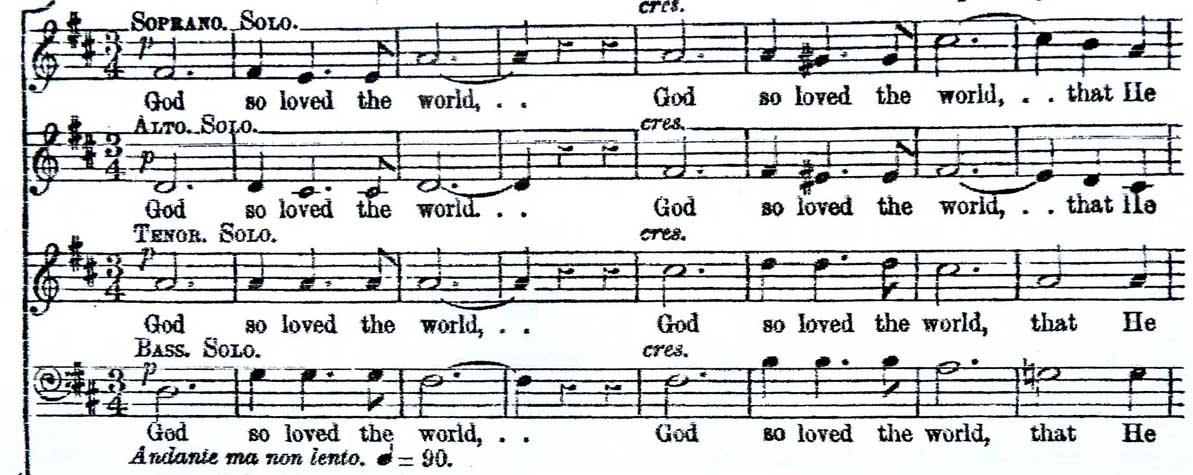

In article 12 I stressed how important it is that one’s choir understands the meaning of the words they sing. Here’s how you may achieve this with some favourite anthems, including Stainer’s ‘God so loved the world’ which many choirs know so well – or do they?

1 Ask your choir to read the opening words: ‘God so loved the world’.

They’ll mumble them, so ask them to read them again with meaning, speaking up as though they believed them, not as though they were reading their tax return. Which word will they stress? Surprisingly it won’t be ‘so’ but it will be ‘loved’. ‘God so LOVED the world’.

‘God so LOVED the world’. I’ve only heard one choir make a crescendo towards the word ‘loved’. (That was the choir of Peterborough Cathedral directed by Dr Stanley Vann.) Singers usually stress the word ‘so’ because that’s how Stainer seems to have felt it. But when the word ‘loved’ is caressed, it completely transforms that phrase musically, and the meaning of the words is immediately communicated to choir and congregation alike.

The word ‘loved’ can sound really lovely if it is sung with two ‘L’s: …Lloved. You can apply this principal to many other words which need special colouring.

RUTTER & WESLEY

Colour your Consonants

For example, (i) in Rutter’s Gaelic Blessing let the word ‘shine’ be sung with two ‘Sh’s: ‘The Lord make his face to Shshine upon you…’ (Text from Numbers, Chapter 6). In Wesley’s 'Blessed be the God' let there be two ‘L’s in Bllessed’. When those opening words are spoken with feeling they begin to flow with an unstoppable sense of forward movement culminating in a triumphant shout ‘…resurrection of Jesus Christ from the DEAD!’. Many choirs sing those opening words in a repressed manner because they’re marked soft. No! Let them be sung with suppressed excitement – as though we hardly dare to believe them. The attitude of mind of one’s singers makes a tremendous difference to their performance.

PALESTRINA

(ii) When the first two words of Palestrina’s motet, Exsultate Deo are spoken with meaning, the choir automatically makes a crescendo and feels a sense of elation when they reach the first syllable of Deo. The music also has an in-built sense of climax – so let it be sung with joy! So many choirs sing Latin (and even English!) as though it were a unknown language. Once they understand the meaning of the words, and begin to believe them, their singing of anthems will be transformed.

It sounds foolish to say so, but there’s no point in singing about anything unless you believe in what you sing. Not all your singers will have the same Christian beliefs but, for the sake of their performance, ask them to pretend that they do.

BACH

Christians Sing!

(iii) The text of Bach’s motet, Jesu, meine Freude, is all about what it means to be a Christian. Its performance can be transformed when the singers (a) know what the words mean, and (b) communicate these truths boldly! The central movement, a fugue, sums up the message of the work: Ye are not of the flesh but of the Spirit. This is joyful news. A difficulty is that Bach sets the word Spirit (geistlich) to running semiquavers, and so a choir’s problem is how to sing them clearly. This can only be done if they are sung lightly, with a slight stress on the first of each group of four semiquavers. Some singers may concentrate on the problem of vocal production and thus lose the meaning of the words. But if the choir responds to the message of the words these melismas will tend to bounce along with joy, for joy is surely what Bach intended.

Again, AGAIN!

2 When a word or phrase is repeated, should the repeat be louder or softer? Try saying, ‘Never, never do that again!’ Clearly, the repeated word is stressed. ‘Never, NEVER do that again!’ And so when your choir sings the second phrase of ‘God so loved the world’ they will (they should) sing it with more intensity: ‘God so LOVED the world, God so LLOVED the world…’ Stainer marked this phrase to be sung louder. But your choir shouldn’t sing it louder because they’ve been told to, but because they feel they really want to. Let there be a sense of thrill when they sing these words for the second time. (Yes, God really does love the world!)

The same applies a few bars further on: ‘… should not perish, should NOT perish…’. And here the forward flow is unstoppable: ‘…but have everlasting LIFE!’ The word ‘life’ is the climax both of the words and of the music. Do your singers feel the elation of this almighty promise by an Almighty Saviour?

Again, AGAIN, AGAIN!!

Rutter also repeats several phrases which call for a livelier stress in his Gaelic Blessing: ‘The Lord make his face to shshine upon you, to shshshine upon you …’

In Jesu, meine Freude there’s a splendid example of repeated words: ‘There is now no, no, NO condemnation to them that are in Jesus Christ’. (Es ist nun nichts, nichts, NICHTS Verdammliches…) The second nichts is marked piano, and so some choirs sing it in a negative, retreating way. But Bach is stressing the joy of salvation by saying that there is no, no, NO condemnation for Christians. So, let the soft nichts be sung (again) with suppressed excitement before it is declaimed for a third time, loudly.

GOSPEL

Just stop for a moment. Does your choir realize that these words define the essence of the Gospel? The same applies to the Stainer anthem. If there were no Bible these two verses (John 3: 16-17) would sum up what we know about our God and our relationship to Him and His relationship to us. Enable your choir realize this – i.e. ‘make real’ the essence of the Gospel in their approach to, and realization of, the words of these anthems.

BREATHE & RUBATO

3 There are two technical problems at the top of the second page of the Stainer anthem. (i) Your singers may run out of breath when they sustain the word ‘life’ for its full three beats. They will need to practise taking a deep enough breath after the first ‘perish’. It would be helpful if you would allow them an extra half beat at that point so that enough air can be taken in. And because this is a ‘romantic’ anthem, it’s permissible to speed up a little for the repeated words, ‘should not perish but have…’ (Subtle rubato is OK!) This will add to the thrill of the words as well as joy of the music.

(ii) The second problem is that Stainer has allowed us only one beat to recover from singing ‘life’ on a high note forte, and then to sing the next low chord piano! It can’t be done in so short a time. So slightly lengthen that one beat rest (conducting it in a relaxed manner) so that your singers can adjust their voices to begin the next phrase softly (‘For God sent not His Son…’) in a relaxed manner.

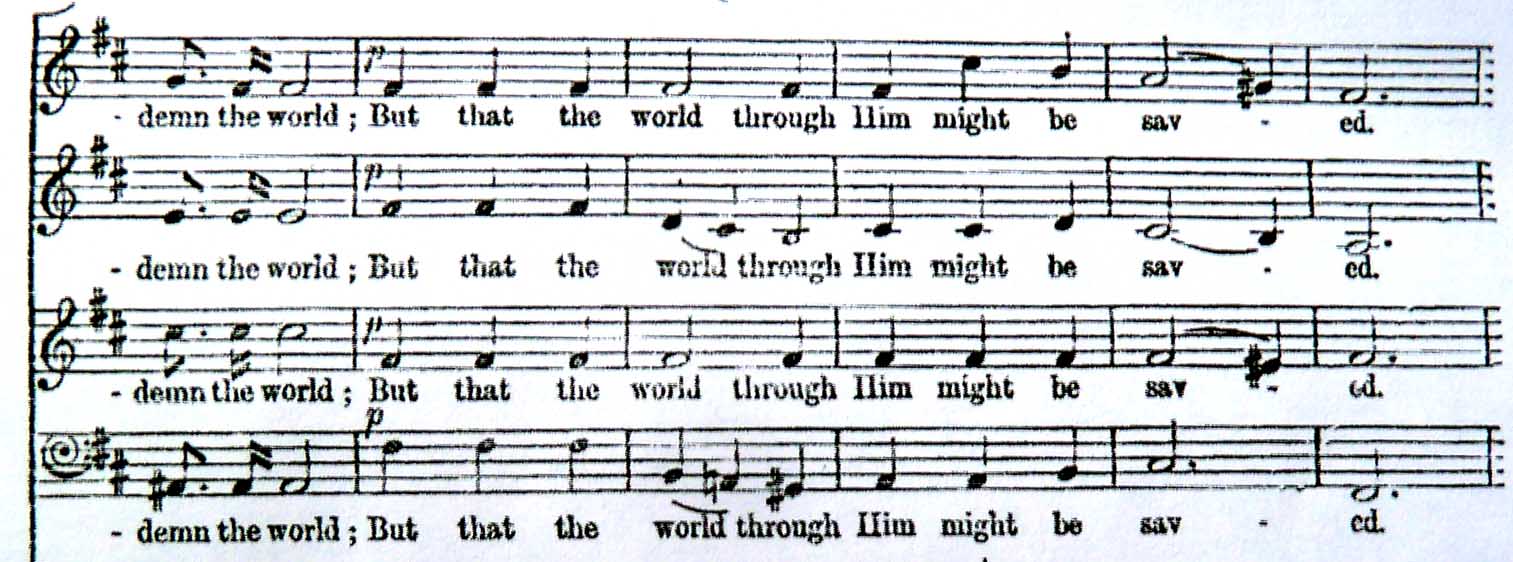

4 There’s a third problem when the phrase is repeated: ‘For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world, God sent not…’) Some choirmasters feel that this second phrase should begin in strict time. When it is sung like this the singers cannot help but ‘snatch’ the word ‘world’ in their efforts to take a quick breath. This ruins the gentle musical flow. NEVER 'SNATCH'!!

STANFORD

Don’t ‘snatch’ breaths

A similar moment of undue stress occurs when a breath is snatched at the top of the penultimate page of Stanford’s Beati quorum: ‘…integra est, (breath) quorum via…’ I’ve even heard some distinguished choirmasters make their choirs snatch a breath after ‘est’ (and so giving an unwanted ‘bump’ to ‘est’) in order to keep the pulse strict. No! Slow down fractionally just before the note where the breath needs to be taken, then allow a relaxed breath – which will mean, in effect, adding a half beat rest – and then take up the gentle flow again. (Rubato is still OK!)

So allow your singers to feel a gentle slowing of the pulse in the Stainer on ‘… to condemn the world’. Let them breathe in that ‘stolen’ rest whilst they and you still feel that the music is moving along, not stopping, and then carry on with the repeated phrase of words which, of course, will be slightly stressed. ‘…to condemn the world.’ Here you could slightly slow the tempo to colour the meaning of these repeated words.

WHISPER URGENTLY

5 The words which follow are usually sung with gloomy hopelessness (because they’re soft): ‘But that the world through Him might be sav-ed.’ But those are staggeringly wonderful words. So ask your choir to whisper those words urgently so that Aunt Griselda in the back row of the congregation can hear them! That will make them very special indeed. Then get them to sing them with the same awed hush.

6 What are you going to ask your choir to do at the top of the third page (when Stainer effectively begins to repeat the whole anthem)? Instead of starting the page with a resigned ‘Here we go again!’ attitude of mind, get your choir to sing those words pianissimo as Stainer intended. You might even add an extra p. That way they will create a sense of transcendence.

How to achieve this? (i) Ask them to sustain that first chord whilst listening to each other, and then to diminuendo to ppp, whilst still listening. (ii) Then to sing the whole phrase. They’ll probably start too loudly, so ask them to remember what pianissimo singing felt like and try it again – and again – and again until you and they are satisfied. (iii) But once they’ve achieved a real pianissimo, beware lest the rhythm gets lazy. All singing needs to be rhythmic, whether it’s loud or soft.

AGAIN, AGAIN, AGAIN!!!

7 You’ll notice that towards the end of the anthem the words ‘everlasting life’ and ‘God so loved the world’ are repeated several times. But here let the progressively softer, rhythmic singing grow in intensity so as to make the music compelling, rather than just ‘beautiful’.

There’s so much more to this anthem than some choirs think. There’s so much more to every anthem than some choirmasters think – until we read the words for ourselves and suddenly realize why the composers were inspired to set them to music.

Let the words inspire you so that you may inspire your choir.

That’s why you’re their choirmaster.

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013