How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

18 Jolly useful WARM-UPS

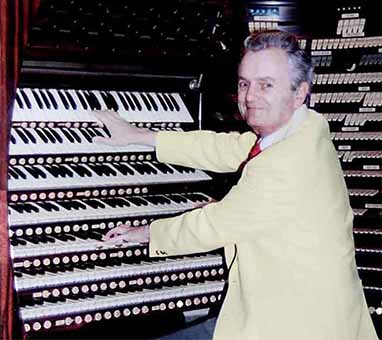

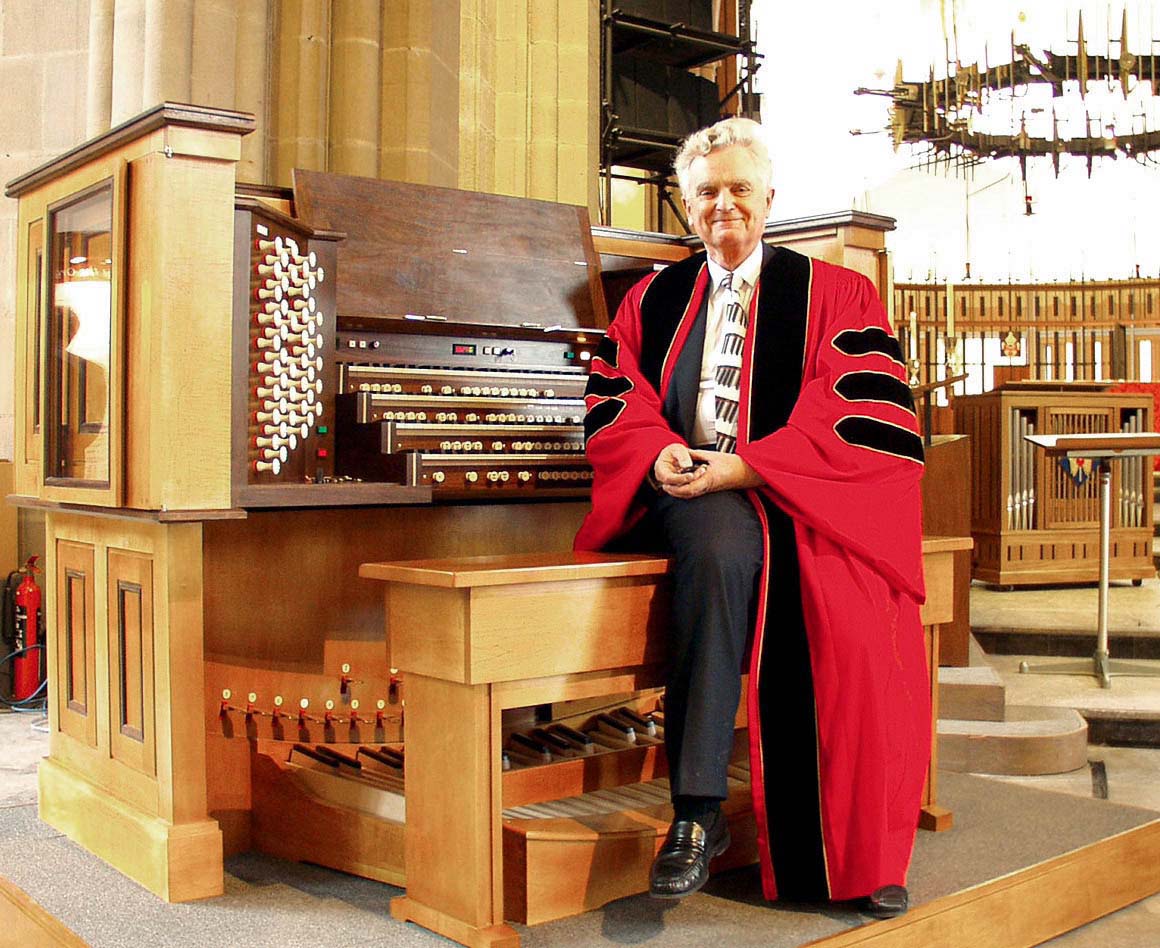

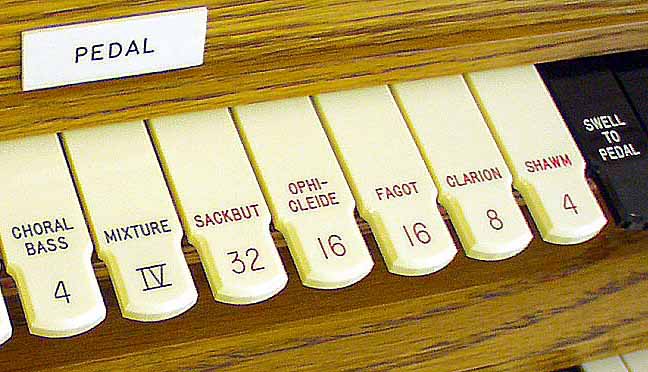

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

BEWARE!!! I recently watched an eminent choir trainer lead his boys in warm-ups.

He played the piano throughout rather well; so well in fact that he expected them to sing with similar accuracy. But they didn't.

HE DIDN'T NOTICE, BECAUSE HE WAS CONCENTRATING ON HIS OWN PLAYING!

His choristers were about 95% accurate - there was, for example, an occasional fluffed note, and they sang nearly together.

And so, what was he training them to do?

1. To sing with 95% accuracy - one wrong note in every 20 (is that good enough?)

2. Teaching them that not singing absolutely together was OK!

And so that's how they sang on Sundays. He thought that they would get better as the practice went on - but NO! The standard we set for our warm-ups is the standard our singers will reach for the rest of their rehearsal - and the results will show on Sunday!

So, do you begin every choir rehearsal with warm-ups? And do you challenge your singers to sing those warm-ups better and better -

RIGHT NOW, BECAUSE THEY ARE SINGING UNACCOMPANIED?

Warm-ups, clearly directed by you, are invaluable to enable your choir to become able to sing at their best for your whole rehearsal within a very short time – if you use them imaginatively.

If you expect your warm-ups to make immediate improvements to your choir’s singing, they will!

What improvements?

1. The choir will come immediately to ‘attention’ (for one cannot train a choir unless every singer is paying 100% attention to what you say!).

2. The standard of their singing will rise noticeably during the first 15 SECONDS of the practice, for as they sing the first few notes of their warm-up, you’ll challenge them to sing even better. "Let’s sing it really together! - TRY AGAIN"

3. They will become more self-reliant, because they’ll sing their warm-ups unaccompanied. (How few choirmasters do this, even professional ones!)

4. Most warm-up repeats rise by semitone steps. This is easy to enable your singers to achieve IF YOU PLAY THE DOMINANT 7th CHORD OF THE NEW KEY. (This is much easier than it sounds. in writing.) Again, few choirmasters or singing teachers seem to do this – and it’s so simple. See below

Let’s demonstrate this with an easy warm-up.

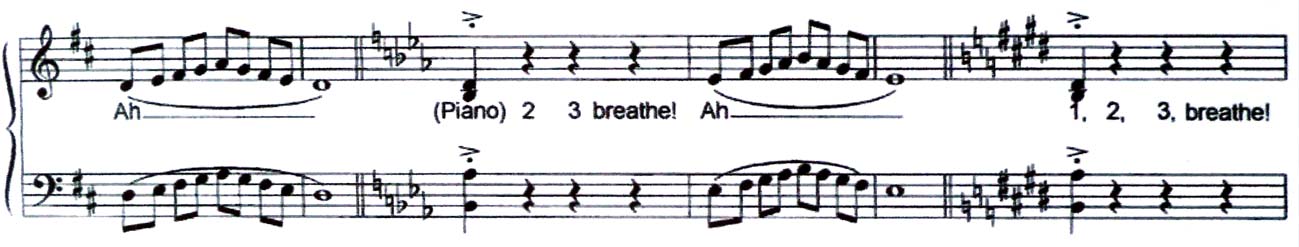

At typical warm-up process for my village church choir is to sing exercises to an open 'Ah', and then to get them to repeat that warm-up by raising their standards through short questions:

Was it wholly together? No! So I immediately said, ‘Look at the leader on the opposite side and breathe exactly one beat before you start.’

It was better, but not all singers sustained the last note for four full beats. ‘Which beat should you come off on? The 4th or the 5th?’ They knew the answer, and so they did it again, and it was right. (That’s how to raise standards immediately, by getting your choir to sing a passage three times before you’re satisfied.)

But we did more with this exercise. It’s worth repeating that the best definition of a choir I’ve ever heard is ‘A choir a disciplined body of singers.’ Warm-ups are the surest way to get your choir to sing well, and to become (self) disciplined. But how to get them to feel that they are a corporate body? Read on!

‘After you’ve held the last note for four beats, feel the next four beats’ rest between each exercise, and then breathe exactly one beat before you sing!’ I then stepped back and let the choir leaders take over – one beater on each side.

Needless to say, one or two singers came in too early during the first rest, so we had to try it again. But they didn’t need a third attempt, for they all felt those four silent beats splendidly. And that is how they instantly became a ‘body’, for they were all feeling the silent rhythmic beats without any help from me.

I suggest that very few amateur choirs (and not all professional choirs, alas!) cultivate a corporate sense of rhythm. But by enabling your choir to feel beats silently, and then to sing the next note firmly, they will be one of the exceptions – and it’s so easy to achieve.

We sang this exercise up to the key of A by semitone stages, with the top note being E, to keep it comfortable for the altos and basses. By the way, it’s essential, when singing warm-ups, to allow your choir to do a lot of singing; some choirmasters think that singing just one or two scales is sufficient to lubricate voices. No! Let your choir sing, almost continuously, for five or more minutes. And constantly encourage them to sing better and better with an open throat, deep breathing, lips forward, stance, singing together…

You can vary these exercises week by week through slight changes of rhythm, or notes. Give your choir different warm-ups every week. It will keep them on their toes.

A useful exercise to encourage the singing of high notes is:

It’s important that every exercise is sung in one breath, and that there’s a crescendo on the second note which leads to the higher third note. I’ve found that my basses and altos can eventually sing a top G if everyone’s encouraged to lower their jaws loosely, and look slightly surprised! So many singers look worried when they’re trying hard; this doesn’t help good tone production. But raising the eyebrows does. Try it! Start on C or D, and then raise each exercise by a semitone, encouraging your singing to enjoy their singing.

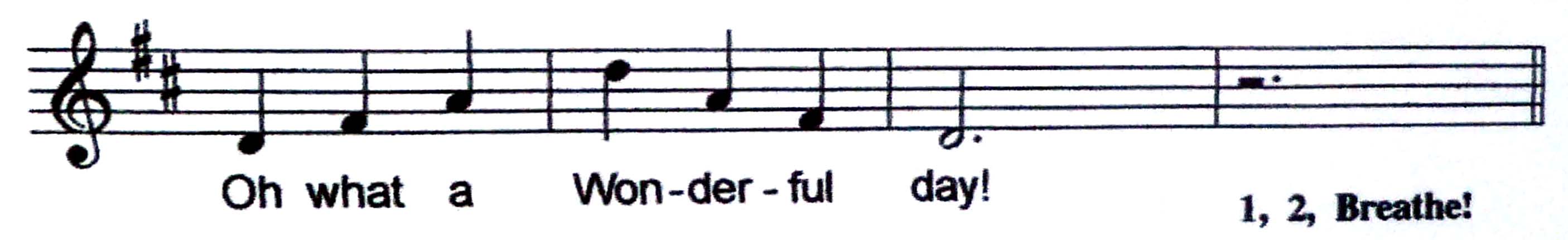

Dr. Barry Rose used this warm-up when he visited the choristers of Blackburn Cathedral recently.

I tried it with my village choir, and they loved it. Sing ‘Wonderful’ with a slow ‘W’ –‘OOOone-derful’. You can make up your own words to apply to your situation. ‘Why is it raining today?’ ‘Let’s start the practice on time!’ This exercise can also be sung in canon, with one side of the choir coming in one bar after the other side.

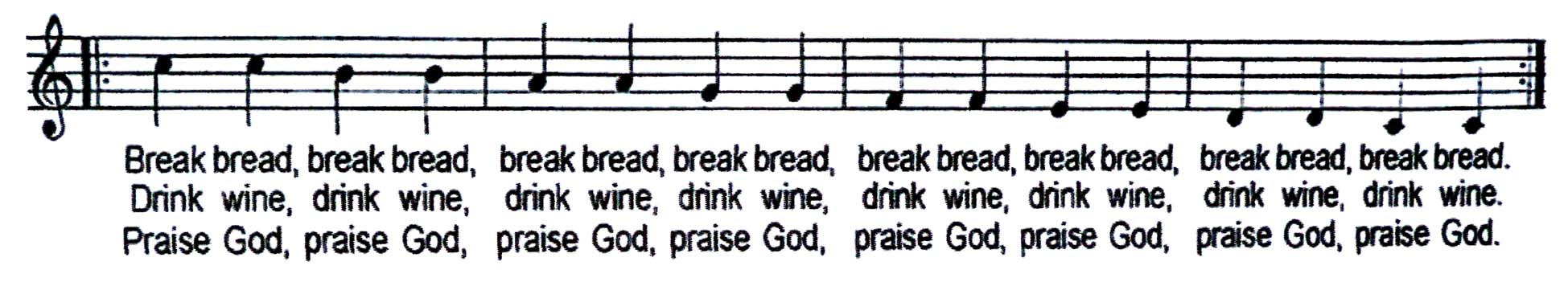

There’s much to be said for tailoring your warm-ups to relate to some of the music you’re singing on Sunday. A facourite communion anthem is 'Let us break bread together on our knees'. It's important that the choir sings the consonants very clearly – rolling their Rs and sounding their Ds. So I ask my choir to sing ‘Break bread’ to a downwards scale, really emphasizing the Ks, Rs and Ds.

Then they sang the scale again to ‘Drink wine’, and finally, of course, to ‘Praise God’.

By this time they really were singing the words very clearly. So I made it even more fun by asking them to sing the three scales without a break. They were working very hard – but they enjoyed every moment. There was one more challenge: ‘Now sing it in canon, with the basses starting, the altos coming in one bar later, then the sopranos and finally the tenors!’ It was a glorious sound, but they had to sit down afterwards for they were exhausted! And that’s how a choir should feel after every practice: exhausted but thrilled at what they’d achieved.

Finally, there’s a very useful warm-up which enables your choir to sing in tune with each other and maintain pitch. The secret is to get every singer to listen intently to every other singer.

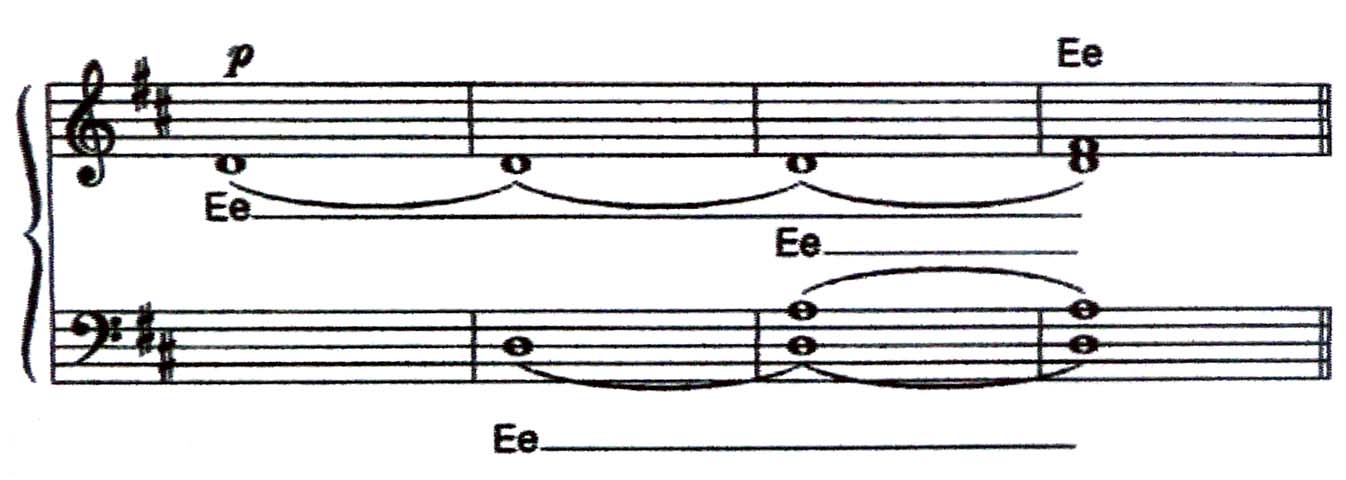

Tell your choir that they are about to sing a chord, but they need to listen to each other to be able to sing their own note exactly in tune. Start with the altos singing a soft D on the vowel Ee. (All singers may breathe when they need to – the sound should be continuous.) ‘Basses! Listen to the altos’ D and then sing your D exactly an octave below.’ Let the sound of the octave Ds continue for a few seconds so that everyone can hear that it’s wholly in tune. ‘Tenors, think of your note which is an A. Pitch it very slightly sharp.’ Let everyone experience this bare-fifth chord – it will sound mediaeval! And finally: ‘Sopranos, think what an F sharp should sound like. There’s only one place where it can fit exactly into the chord – so think of it slightly sharp too, and sing it gently.’

Your choir should experience a rare event – singing a chord exactly in tune. If it doesn’t work, define where the problem is (for tenors and altos sometimes sing slightly flat), and try it again.

The chord can be formed in any number of ways, but always bring the voices in the same pitch order: A fairly high tonic, another tonic an octave or two octaves lower, then the fifth and finally the major third. The first two notes are the simplest to tune, the fifth and the third need more care, so they come last.

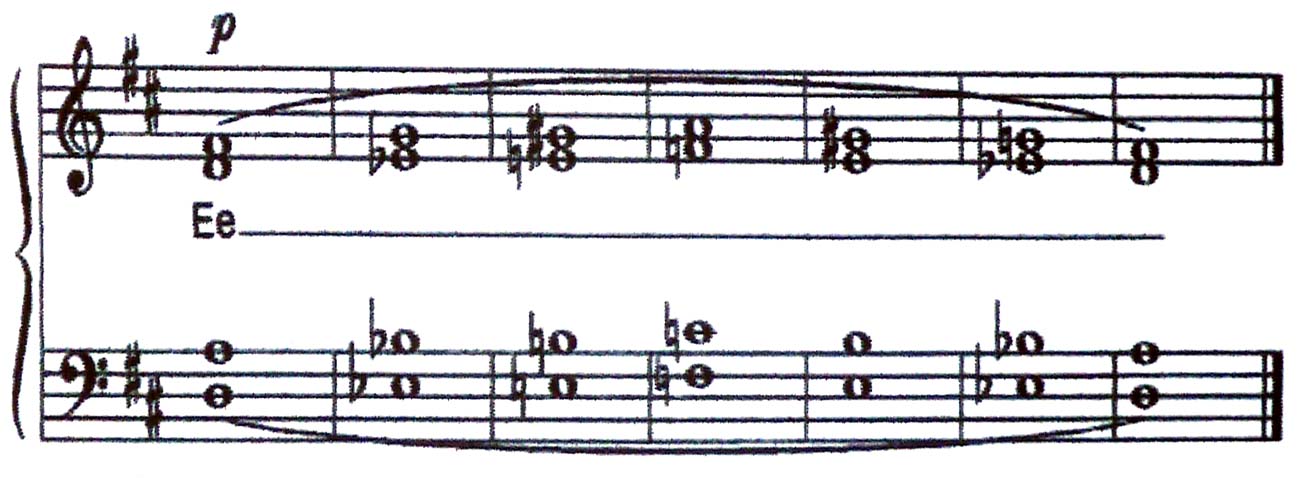

And if your choir is geared up for really accurate intonation, ask them to sing the following exercise, slowly and softly, breathing whenever they have to, but not when changing their note. I used this with my choirs in the USA – especially when we were about to make a CD of unaccompanied music.

This takes critical listening to each other to the ultimate, for it’s essential if the chords are to be wholly in tune. Check the pitch of the last chord to see if it’s the same as the chord they started on. If it is, you’re winning – and so are they!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013