How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

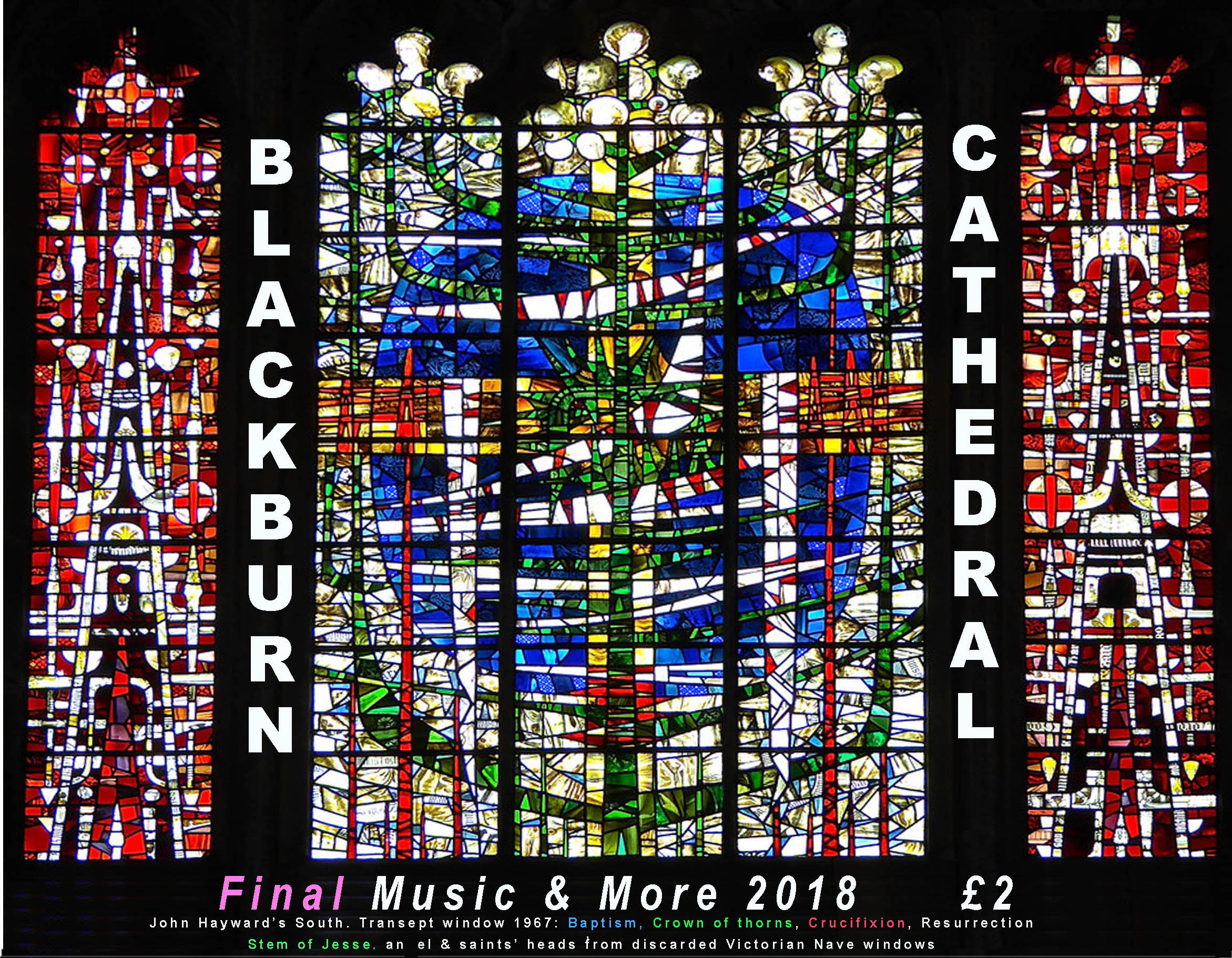

20 The Eyes have it

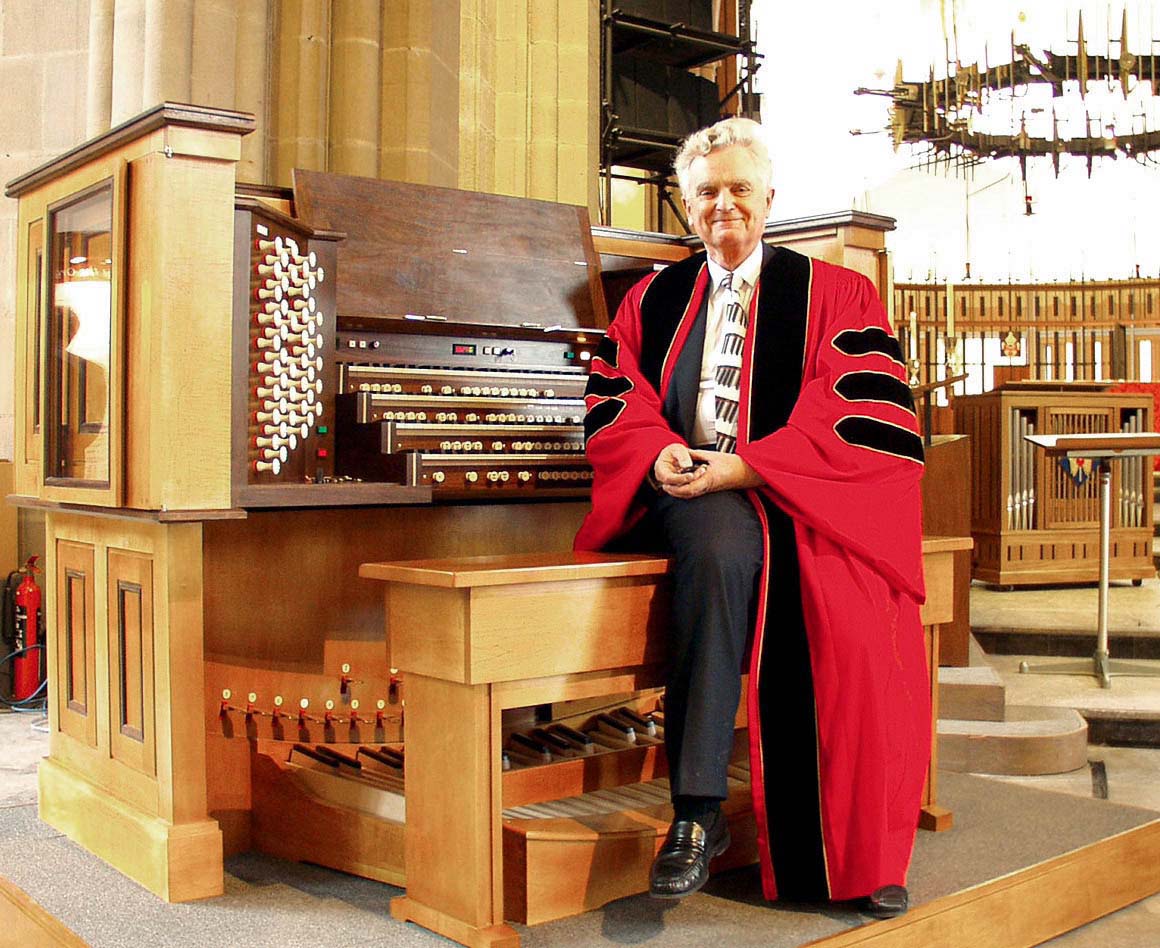

John Bertalot rehearsing the choirs of Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ

N.B. conducting without music and looking at every singer with every singer looking at JB

When I visited the historic parish church of Nutfield in Surrey a few years ago I listened to the most dramatic reading of a lesson I have ever heard. It was read by a 90-year old man who didn’t need glasses, for he declaimed the entire lesson from memory. I learnt afterwards that he memorized his lesson every week in order to keep his brain active.

That was remarkable in itself; but what was more remarkable was that, because he could recite the lesson from memory, he could look at the congregation throughout. To hear the words, ‘Jesus said…’ from a man who was looking straight at you, was an extraordinary experience which I have never forgotten. We felt that this man had been there when Jesus said it! In other words he brought the text vibrantly alive for us all.

What could this mean for those of us who are choirmasters? When Dr. Barry Rose leads choral workshops he stresses the importance of the eyes. ‘You can conduct with your eyes,’ he says. ‘You needn’t wave your arms about – it’s your eyes which tell your choir what you want.’

Recently I was asked to conduct Howells’ Collegium Regale Nunc Dimittis as part of a Choral Evensong which was sung by three choirs. I was given only 15 minutes to rehearse them and so I had to make most of that short time. Therefore I spent the entire 15 minutes making active eye contact with them all without referring to my music. By doing that I was able to command their total attention.

Recently I was asked to conduct Howells’ Collegium Regale Nunc Dimittis as part of a Choral Evensong which was sung by three choirs. I was given only 15 minutes to rehearse them and so I had to make most of that short time. Therefore I spent the entire 15 minutes making active eye contact with them all without referring to my music. By doing that I was able to command their total attention.

At the service, after the second lesson before they stood up to sing, I looked at them with an ‘embracing glance’ (i.e. a slow sweeping look from one side of the choir to the other) which sent the message, ‘I know you’re here; you know that I’m here, and we’re going to make this performance very special.’ I then indicated that they should stand up together. (We’d rehearsed this, for if a choir can’t stand together how can they sing together?)

I then conducted the Nunc Dimittis entirely from memory, looking at the soloist, looking at the organist, looking at the singers and compelling them to sing exactly with my beat. By doing that I was able to control every nuance of their singing.

How did I ensure that they sang precisely with my beat instead of after it? (There were some 80 singers.) At the rehearsal I made sure that they would respond instantly to my smallest gesture: I said, ‘Say the word Pop all together, with my beat.’ I waited for a full 5 seconds, looking at them all intently so that they could focus on my hand, and then, with a small gesture I gave them the signal, and they did it! Then I asked them to sing the word 'God' with my beat – and to sound the final ‘d’ when I brought them off. This worked, too. In other words, I had rehearsed them to sing with me, rather than after me.

I get the feeling, when watching some professional conductors, that they don’t really believe that their singers will come in with their beat, so they either conduct more furiously, or else they think to themselves, ‘They always sing after my beat, because that’s how it is!’ No, it isn’t!

When singers come in after a beat they are telling their conductor that he (or she) isn’t really necessary and that they can sing just as well without a conductor. The trouble is that such conductors don’t know this and believe that they really are controlling their singers. No, they’re not!

It’s the most marvellous musical experience to conduct a choir in such a way that you are controlling and inspiring every note right then and there.

When my Princeton Singers (a semi-professional choir of adults from the USA) sang Evensong at St. Paul’s Cathedral, we were so moved by Canon Michael Saward’s reading of the first lesson, which described King David’s grief at the death of his son Absalom, that when we came to sing Weelkes’ setting of When David heard, I was able to get from them a performance which was entirely different from the way we had rehearsed it. That was creative singing, and they knew it. And that was only possible because I had rehearsed them to sing with my beat rather than after it.

It is my privilege to hear a number of English cathedral choirs; I was most impressed by Dr. Alan Thurlow’s choir at Chichester. Why? Because he looks intently at his choristers, who therefore sang with his beat (he conducts subtly) rather than after it. I have rarely seen such concentration on the faces of cathedral choristers; their dedication and commitment were outstanding.

And so I ask the question of some of my distinguished musical brethren: Why don’t you conduct from memory? If I can conduct Howells’ Nunc Dimittis from memory (the last time I conducted it was over 9 years previously, just before I retired from Princeton), surely you can conduct Responses and even some Canticles from memory, which your choir sings regularly. And why should you do this? In order to inspire your singers with your musicianship to create spine-tingling performances. You can’t do this when you’re continually looking at your music. It’s no good saying, ‘sing with my beat’, they actually have to do it. Look intently at them – for your eyes will command how they should sing. (Some distinguished brethren even look at their music to conduct Amens. That’s pathetic!)

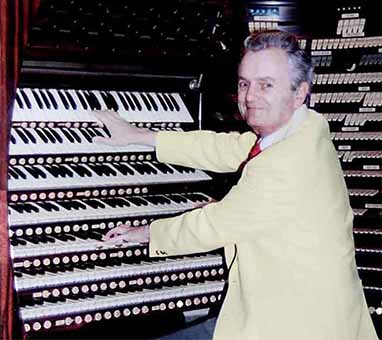

At my rehearsal for the Howells Nunc Dimittis, I said to the basses, ‘Sing the word 'Glory' as though you were a lion about to attack an antelope.’ They did, and at the service someone happened to take a photo of that ‘Lion’ moment. The eyes said it all. See below

Listen to that moment from a recording taken at that service: Notice that on the final fortissimo chord of the Gloria the choir actually made a crescendo. Howells should never be sung 'straight' but always with a rise and fall of expression - like waves undulating upon a gentle sea.

But if your choir doesn’t aspire to sing such ambitious music, you can still inspire them by looking at them much more creatively.

You may not be aware that your head is in the music when taking a choir practice; you may think that you’re looking at your singers, but almost certainly you’re not.

Try rehearsing a hymn without the music in front of you, and see how much better your choir sings from the message that your eyes give them.

The eyes have it!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013