How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

22 I will sing with the Spirit

and with the understanding also

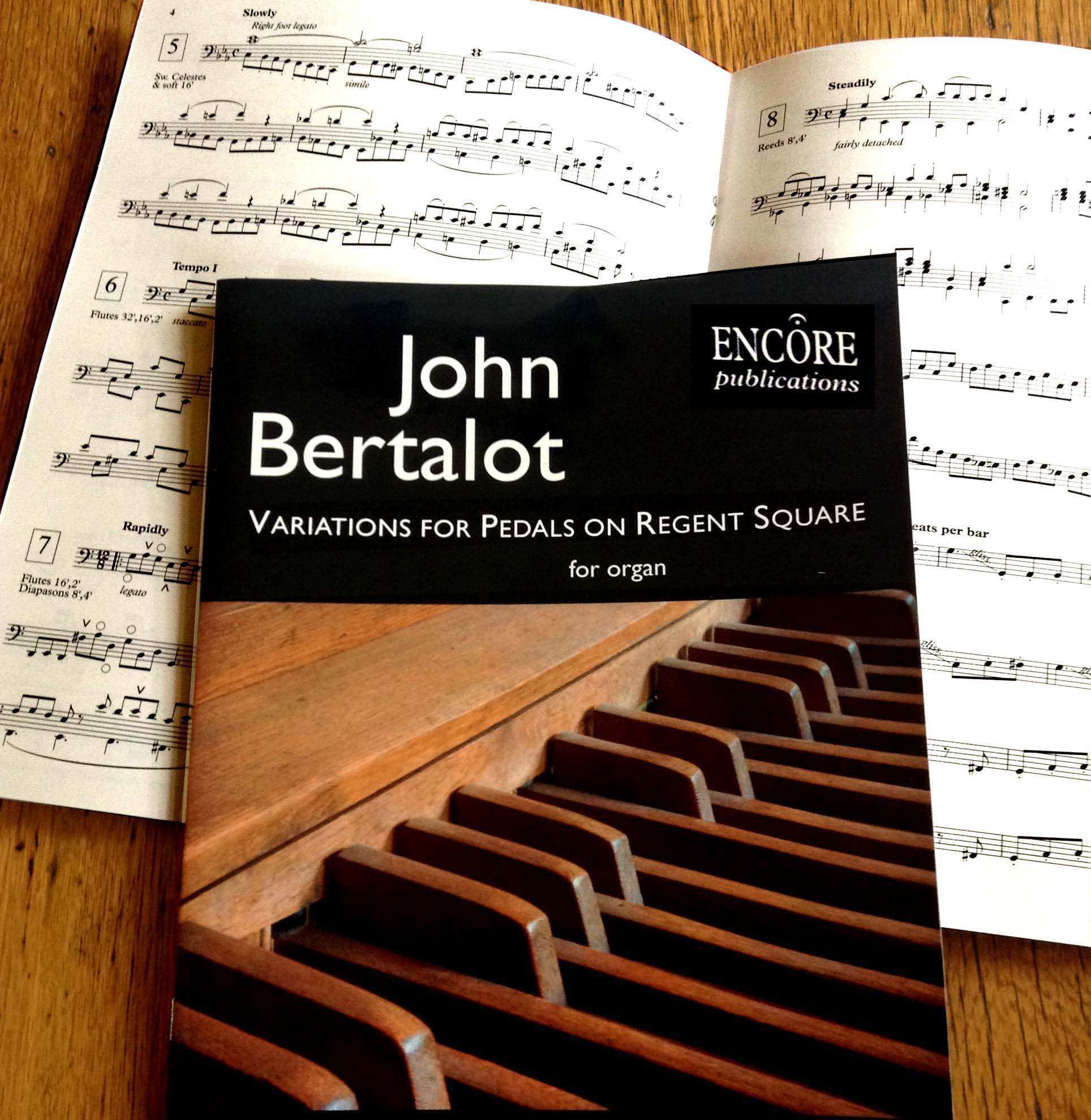

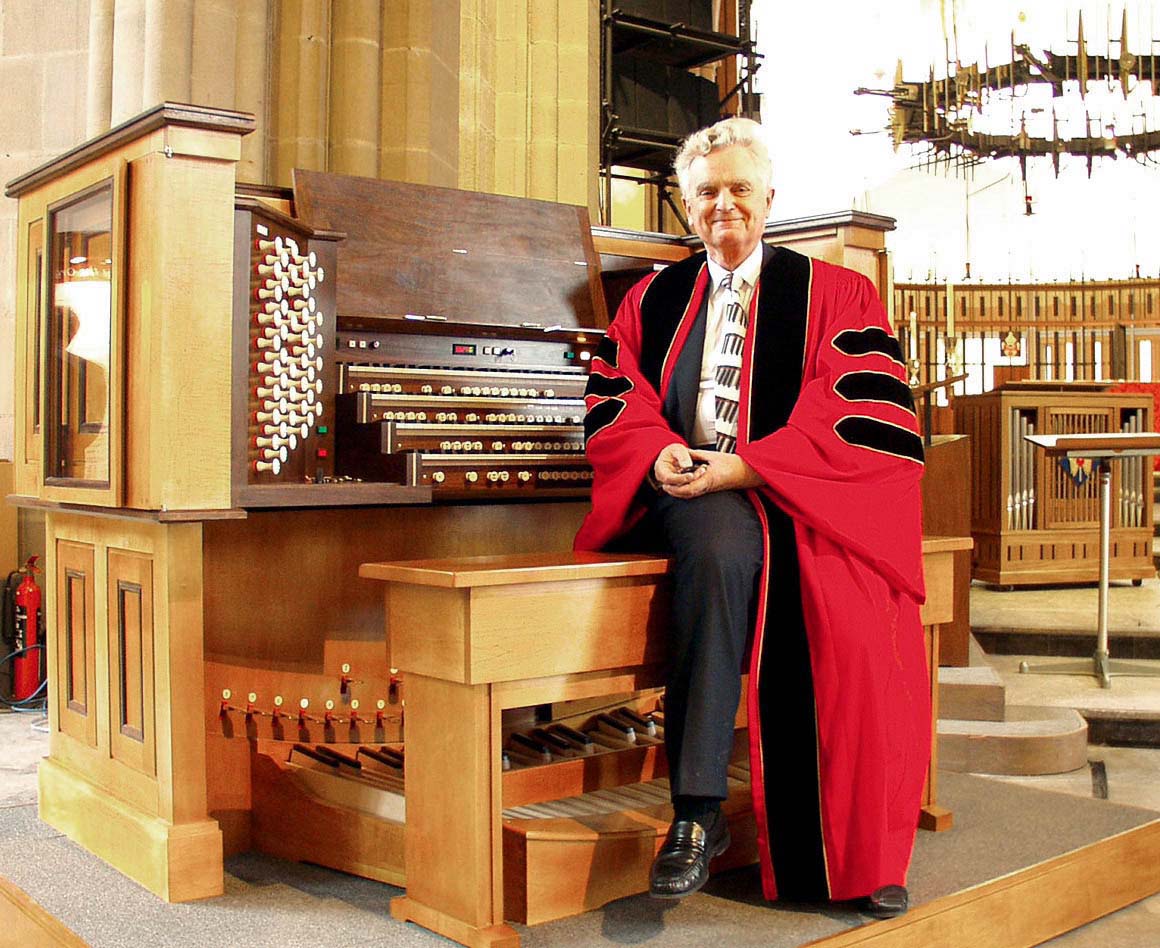

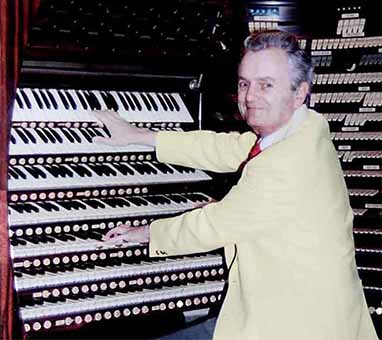

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton.

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

PSALLAM SPIRITU ET MENTE

Choirmasters need to explore what the RSCM’s motto, I will sing with the spirit and I will sing with the understanding also, means in practice – in choir practice.

Question: does your choir sing all their music – their hymns and their anthems – with their spirit and with their understanding? i.e. Do they always sing the right notes and observe all dynamics, and do they also understand what they are singing about, so that they can communicate to the congregation the message of the words which inspired the composers to create that music?

In practice it boils down to the choirmaster knowing and loving every note of the music, and every blessed word of the text - i.e the message of the Gospel, for it's those words which inspired the composers to create that music. The words come first, the music illustrates and colours the texts.

If you’re like so many other choirmasters, when it comes to rehearsing a well-known anthem or canticle, you may well think, ‘We’ve sung this many times before – it only needs brushing up.’

Take a well-known case in point: Stanford’s Nunc Dimittis in B flat. We all know this. It’s for men’s voices, marked ‘Slow’, it gets faster and louder in the middle and ends softly, with a dignified Gloria for full choir. ‘We needn’t spend much time on this for we sang it only a few months ago.’ But did you notice precisely what Stanford wrote?

1. It’s in 2/2 time, not 4/4. Two slow-beats per bar can be twice as fast as four slow-beats. I have never heard any choirmaster conduct this Nunc Dimittis in 2/2 time. I’m sure that there are many who do, but I’ve not been there when they’ve done it. I’ve seen three or four distinguished choirmasters try to conduct the opening in minim beats, but pretty soon break into crotchet beats especially when it gets faster. (‘They won’t sing faster unless I crack the whip!’) This is exactly the wrong thing to do.

What choirmasters need to do is to rehearse their choirs into singing faster at that point, and that means, in practice, to get them to practise the join of those two sections: ‘…of all––– peo––ple. [Strong second downbeat] To be a light…’ The word ‘To’ must be squeezed in immediately before that second beat. And choirs need to rehearse this at least three times before it becomes automatic. Conductors needs to know that the singers know that they will sing that change of tempo in the service because they’ve rehearsed it to perfection in rehearsal. That’s what rehearsals are for.

2. A few bars further on the men sing, ‘and to be the glo––––––ry of thy peo–––ple Israel’. When this is conducted in crotchets (as every performance I’ve witnessed so far has been) this puts an intolerable strain on the men’s voices, for they are singing interminably high notes loudly. Singing this passage twice as fast makes it immediately singable (rather than barely endurable) and so it becomes a glorious climax to this canticle.

3. But the result of singing this particular passage in crotchets is that the men run out of breath, and so they end that phrase softly. Stanford did not write a diminuendo there! He meant that phrase to end triumphantly. Simeon has seen the Messiah, as God promised, so he is full of joy. To reinforce the message of joy and fulfilment, you could encourage your men to make a crescendo on the word ‘Israel’. The organ must remain loud as well, as Stanford intended.

4. But then Stanford repeats the words ‘thy people Israel’, and they are sung softly. Why? Perhaps Stanford pictured the old man tottering away, repeating the words to himself under his breath. Perhaps that’s why he sets Simeon’s words to be sung by the men only, rather than by the full choir. The mood has changed within only a couple of bars, from portraying the triumphant fulfilment of a prophecy to an old man who’s not too steady on his feet. Is this over-romanticizing this music? I think not. When it is sung in this way the choir and the congregation can the more easily see faithful Simeon taking the Babe joyfully in his arms, and then returning Him gently to his mother.

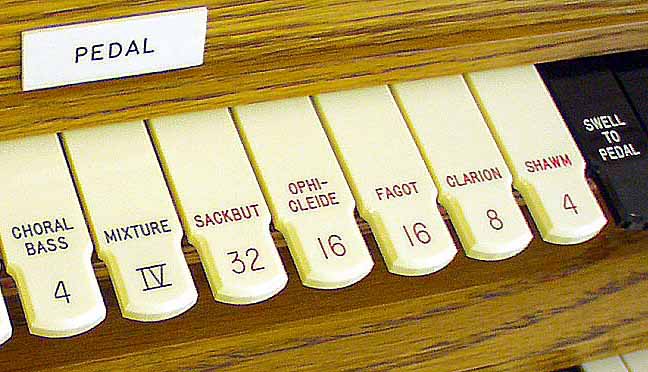

5. Your performance of this simple, but exquisite setting of the Nunc Dimittis will stand or fall by the way the organist and choir attack the very first bar. Can your accompanist feel those first two crotchets with a minim beat? To ensure that your organist can, conduct a precise ‘empty’ bar in 2/2 to ensure that the first two notes of the organ are a springboard for the choir to come in exactly (not nearly) on the 2nd beat.

The beginning of every musical work is the key to how the whole work will be sung, so always make sure that your choir (every singer, not just most of them) comes in precisely with your beat, and not after it.

Listen to the recording of this Nunc Dimittis sung by the choir of Blackburn Cathedral, with James Davy at the organ which I was privileged to conduct as a celebration(?) of my 80th birthday. I've included the Gloria - notice the attack of the choir on the first word 'Glory' and also the crescendo on the word 'World'. (Whenever there's a long note in music, it nearly always needs a steady crescendo to make it live! And the Amen is loud, to give a triumphant ending to this so-expressive setting.

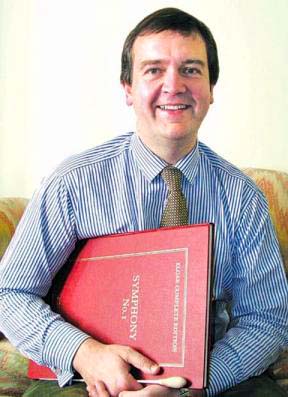

Adrian Lucas, the dynamic former Director of Music of Worcester Cathedral,

has published a realization of these Stanford Bb Canticles, basing the organ part on Stanford’s orchestral version. It’s a real eye-opener, for it transforms this, perhaps, under-valued setting, into a real classic. (This is the setting we sang at Blackburn that day.)

For example, in the usual version, the organ part at the end of the Gloria is marked diminuendo, but not the choir! The choir, therefore, should sing the Amens loudly. Every choir I’ve ever heard tries to sing them softly – and it doesn’t work. But Mr. Lucas ensures that the choir still sings the Amens loudly by writing the instruction [sempre forte]. Further, he suggests that ‘Slow’ at the beginning of the Nunc Dimittis should be minim=60. That, surely, is the pace that Stanford intended.

But there’s more, much more, to Mr. Lucas’s transcription of these Canticles: look at the organ part of the final bars of the Gloria of the Magnificat:

(Reproduced by permission.)

Now listen to the Gloria sung by the Choir of Blackburn Cathedral conducted by John Bertalot to celebrate his 80th birthday, with James Davy playing the organ.

Isn’t that thrilling? Copies are available from Adrian Lucas. Enquiries to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Listen to the choir of Blackburn Cathedral singing this Gloria when I conducted it for my 80th birthday, with James Davy at the organ.

There are many other well-known works which have clear instructions which many choirmasters don’t notice:

Charles Wood’s Collegium Regale Nunc Dimittis has the melody sung by 1st tenors and 2nd basses mp whilst the rest of the choir sings either piano or ppp. In other words, the melody should be heard clearly at all times. I have yet to hear a choir sing ppp. It should sound as though the choir was in another room with the door shut – i.e. hardly audible. All too often it is much too ‘present’ and the melody is swamped. So rehearse the ppp sections by asking your choir to hum those notes. This will show them exactly what really soft singing feels like.

Another example of un-noticed instructions comes in Duruflé’s Ubi caritas. The plainsong melody is clearly given to the altos at the beginning, for the sopranos are silent. But when the sopranos do come in they have the plainsong melody for only four bars. After that Duruflé returns it to the altos with instructions (in French) that they should sing ‘a little forward’ of the other voices. I have yet to hear a choir which follows this clear instruction, for once the sopranos have started to sing, they think that they have the melody throughout. They haven’t.

But perhaps your choir doesn’t sing anthems or canticles. What about hymns? In the first verse of Amazing Grace it’s so easy to sing ‘I once was lost’ cheerfully (for the notes are fairly high) and ‘but now am found,’ dismally (for the notes are lower). This, of course, makes nonsense of the text. Similarly in Just as I am, many choirs, rightly, sing the first line of verse 3 penitently: ‘Just as I am, poor, wretched, blind'. But they often begin the next line in a similar remorseful way until it’s too late, for this should be triumphantly loud!: ‘sight, riches, healing of the mind, yea, all I need in thee to find…’

In other words, in almost every piece of music your choir sings, be they hymns or anthems, there are precise instructions, or implied instructions, how the composer intended them to be performed.

And you, their choirmaster, can only discover these instructions if you study the music before you lead your choir practice – especially if you’re rehearsing something which is well-known.

So, if you want your choir to ‘sing with the spirit and with the understanding also’, you have to do something about it right now!

It's called doing your homework!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013