How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

25: Personal Relationships

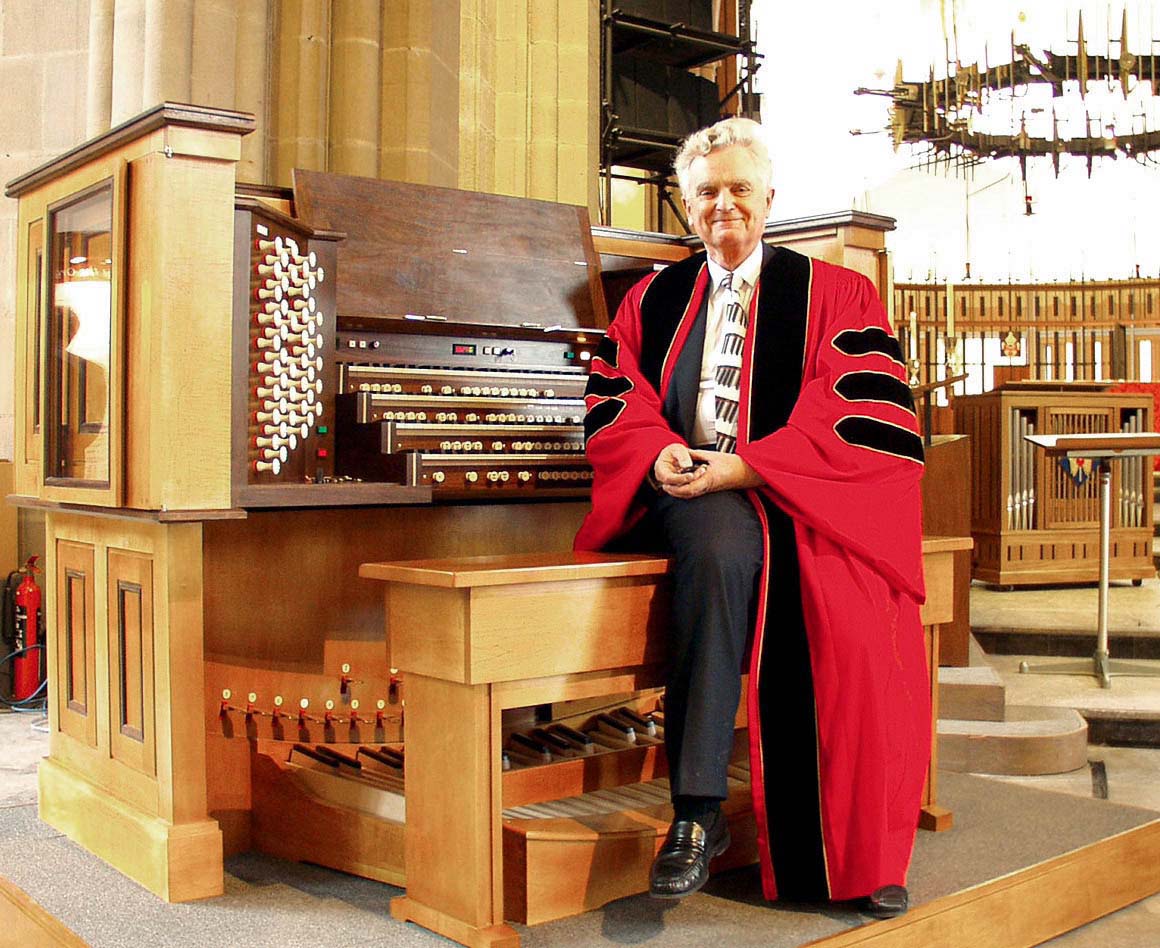

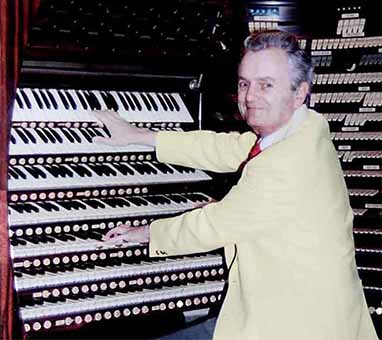

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

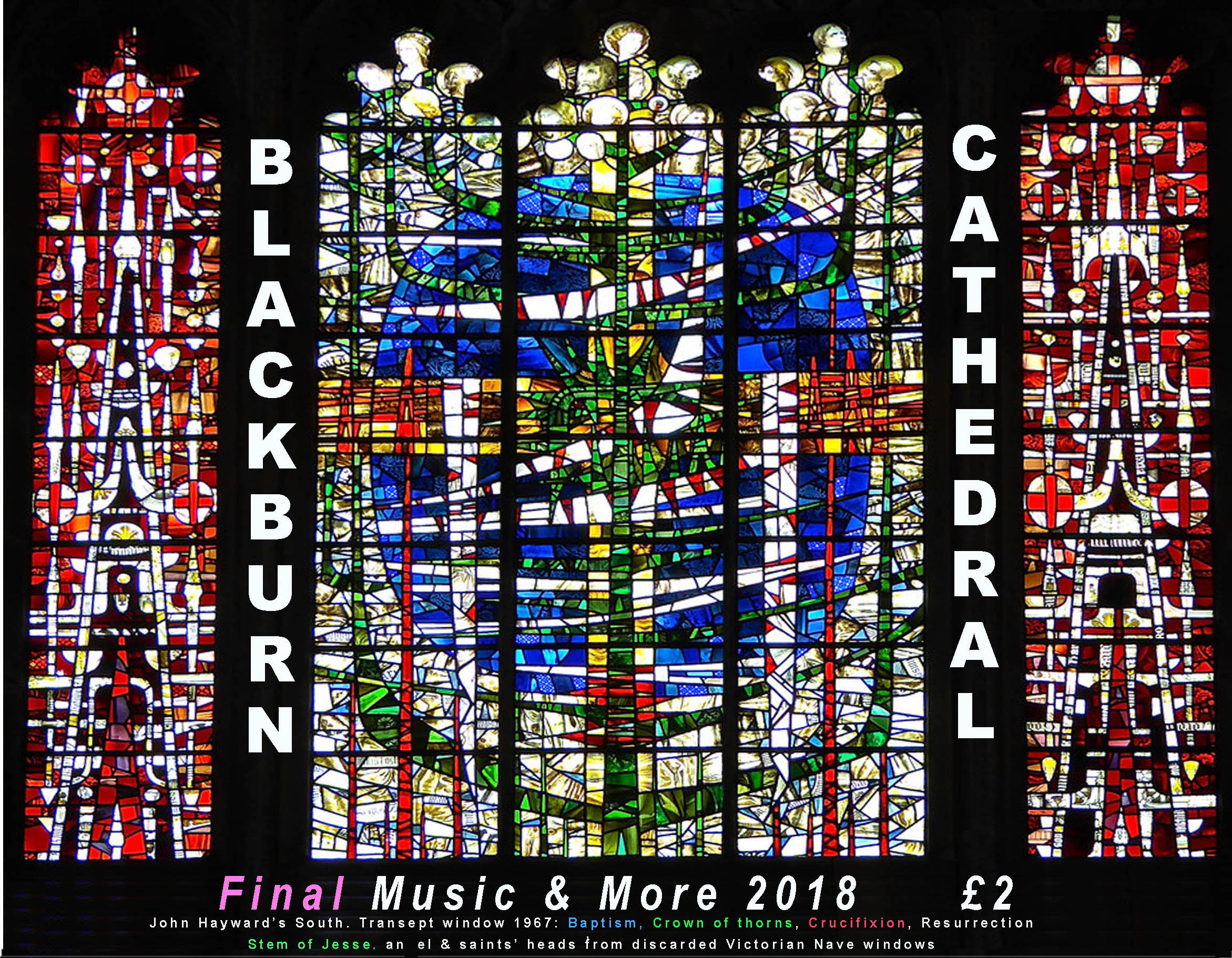

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

With Priscilla Rigg, a musically and pastorally gifted choirtrainer in Rhode Island, USA

When I led a choral workshop for diocesan choirmasters at Hereford Cathedral, I asked them what their greatest choirtraining problems were.

Their questions came under three headings:

(i) personal relationships,

(ii) commitment, attendance and maintaining the interest of one’s choristers, and

(iii) how to encourage children.

Let’s deal with the first of these now, and the last two in subsequent articles.

Personal relationships. How to deal with pushy parents and difficult choir adults.

A choir is not only a musical body, but also a social body. Members need to ‘fit in’ with each other in every way. Therefore when someone intimately connected with the choir, either as a singer or parent, becomes ‘difficult’, they will affect the other members not only socially but also musically. And it is the choirmaster who has to bring harmony into this situation. How?

One of the most memorable techniques I learnt as a student in Dr. E. T. Cook’s choirtraining class at the Royal College of Music last Millennium [sic] was, ‘If you have a difficult tenor, get to know him better over a drink in the local pub!’

Choirmasters generally see only one side of their singers’ personalities – their musical side. But there is much more to them than that. (And there’s much more to you, as well!) Therefore get to know them as whole people rather than just ‘singing units’, and enable them to get to know you as a person rather than as a choirmaster.

There are many ways in which this could be approached:

(a) Invite this person and his/her spouse to lunch or dinner at a restaurant. (Why not in your home? Because this could be threatening to your guests, as it is in your own territory. Therefore choose neutral territory where you may all feel at ease.) To help with the setting up of this meal, invite another couple as well so that no ulterior motive may be suspected.

Should you discuss the problem during the meal? No! Let it be entirely social – enjoying each other’s company, and ending the evening on a convivial note. And, of course, follow this up with a hand-written letter saying how much you appreciated getting to know them better.

The next time you meet this person in a choir situation, see if their attitude to you has softened. One of my Deans at Blackburn had a most useful saying: A difficult person is a person with a difficulty. And so, because you now know each other better, perhaps you might have discovered what their difficulty is. And perhaps you might discover that you had a difficulty yourself which needs your own attention! It takes two to quarrel, for no-one is perfect.

If you are a patient listener, this person may want to share his/her problem with you. (Make sure that your door is open!) To show that you are hearing what is being said, repeat back to that person what you’ve just heard, but in different words. The response to ‘I don’t like some people in the choir!’ could be, ‘You’re feeling uncomfortable, aren’t you.’ But beware if this sort of exchange goes any deeper, for it is not your job to listen to folks’ confessions. Do not allow yourself to see this person one-on-one again. You should go straight to your minister to report what has happened, so that he may take over this situation completely.

(b) Regular late-comers are late because they will be noticed. (‘Now that I’m here the practice can really begin!’) They need help to realize that they are important to the choir – but so are the other members.

So give that difficult person a job to do which will help the choir. This person is saying by his/her attitude, ‘I want to be noticed.’ Well, let them be noticed by giving them some responsibility. I had a particularly difficult person in one of my choirs some years ago, and so I made him choir librarian. He did the job magnificently, keeping the music in apple pie order, and also keeping the singers, and me, up to the mark in returning copies punctually and neatly. He was still a difficult person, but his energy was channeled into helping the choir rather than hindering it.

Another task might be to ask them to organise a choir party. Every singer should bring some food or help with its serving or with the tidying up afterwards. Regular choir parties in each other’s homes can give a real boost to your choir’s sense of wholeness.

Similarly, regular parties for choir parents are also a means of oiling personal relationships. Provide name labels which include the name of that parent’s young chorister.

Such active participation in your choir programme will certainly enable your problem person to be noticed and appreciated for, basically, that’s why they’re being difficult.

(c) Discuss the situation with your minister, for ultimately the spiritual health of the church is his responsibility and he will have been trained to deal with such situations. (If you have regular meetings with your minister, you should have discussed this problem person already.)

A gentle word of advice: never say anything critically about any of your singers or their families to anyone, for if you do, your words will eventually get back to that person, and this will make the healing of your relationships virtually impossible. Instead, try to find something positive to say about that person when speaking with someone else – cast your bread upon the waters – and it could eventually return to you in the shape of a healed relationship.

One of my Rectors in the USA said that his job was so rewarding that he would do it ‘for free’. But he got paid for doing the difficult jobs – which were usually about trying to heal unhappy personal relationships. A church is a place where its members live with their feelings very near to the surface. And so those of us who exercise a leadership role need to be able to deal with such situations in a delicate, sympathetic manner. This is not easy and you won’t turn your pushy parent, or difficult singer, into a saint. But you might make it easier for that person to be a more valuable part of your choir family, and this will help everyone.

(d) And finally, pray for that person regularly. Prayer does change things. Prayer might change the attitude of that person to you, but your prayers will certainly change your attitude to that person – and you may eventually discover that that’s where the problem might lie! I’ve found it helpful to pray for each member of my parish church choir by name on Sunday mornings before I go to church. That way I feel that I’ve ‘met them’ already, and my attitude to each singer is one of active goodwill. They return this goodwill to me in abundant measure. The same could be true for you.

But there’s more to encouraging good personal relationships.

‘Pushy parents’ are almost certainly pushy because they want the best for their children in your choir. All parents want their children to do well, and so it will be your job to channel their pushiness to help the choir, and thus help their children, rather than hinder it.

And so, look at your own organisation first. Is your choir efficient? Is it geared to success? Do your members feel that they belong to a choir which is an exciting body whose every practice is worth coming to? If not, then perhaps your pushy parents may have a legitimate cause for being difficult. It takes two to have a disagreement, so look to yourself first, and then see how positive changes could be made to enable these parents to become more cooperative.

Perhaps these parents could help to raise money to send some of the children on a residential choir course? Choir courses can be a time of inspiration not only for those who are attending, but also for the whole choir when the children return, energized and actively enthusiastic.

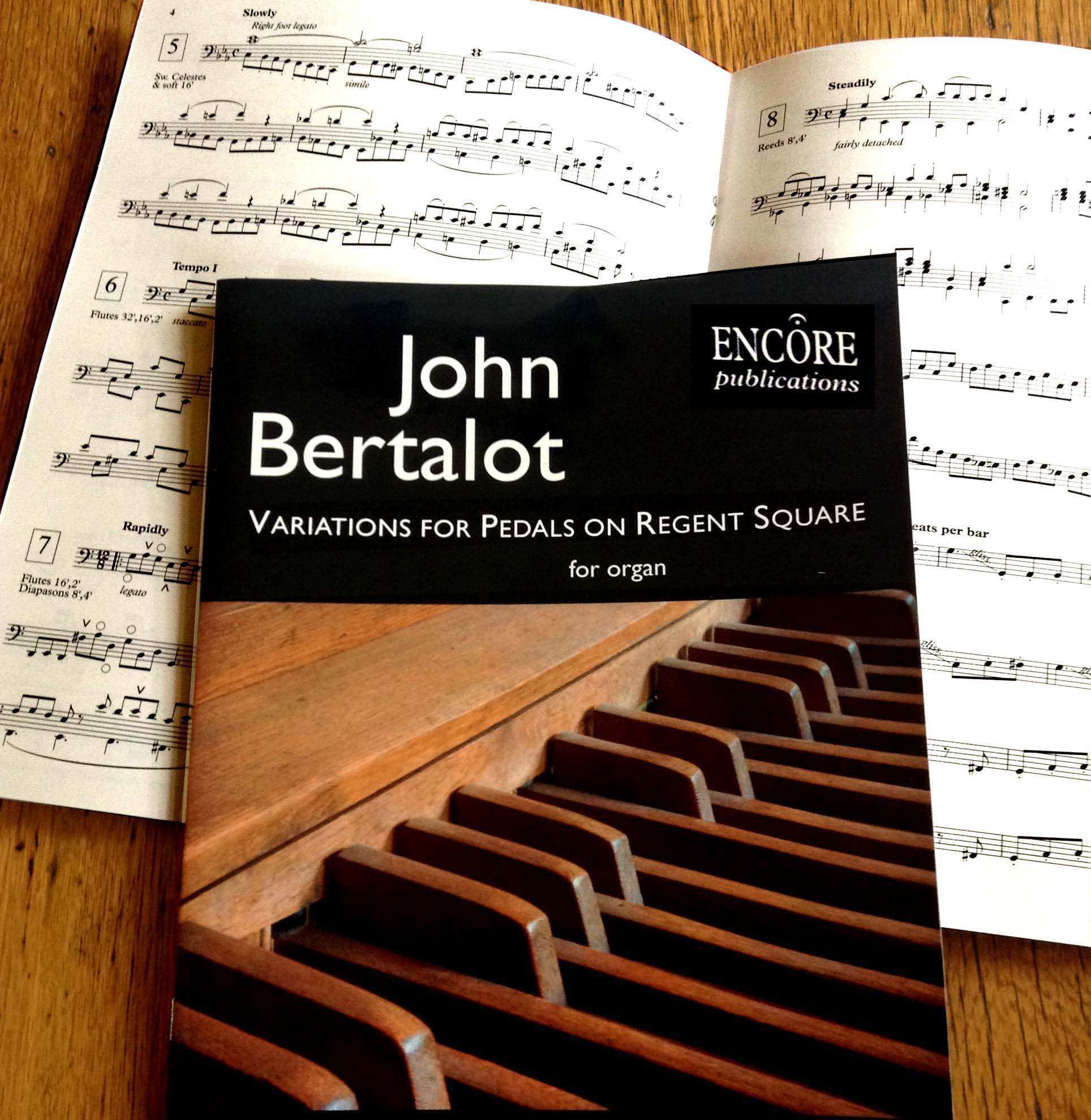

All the articles I have been full of practical ideas to help raise standards and promote enthusiasm – I’ve tried them myself, and they do work. See my books on choirtraining.

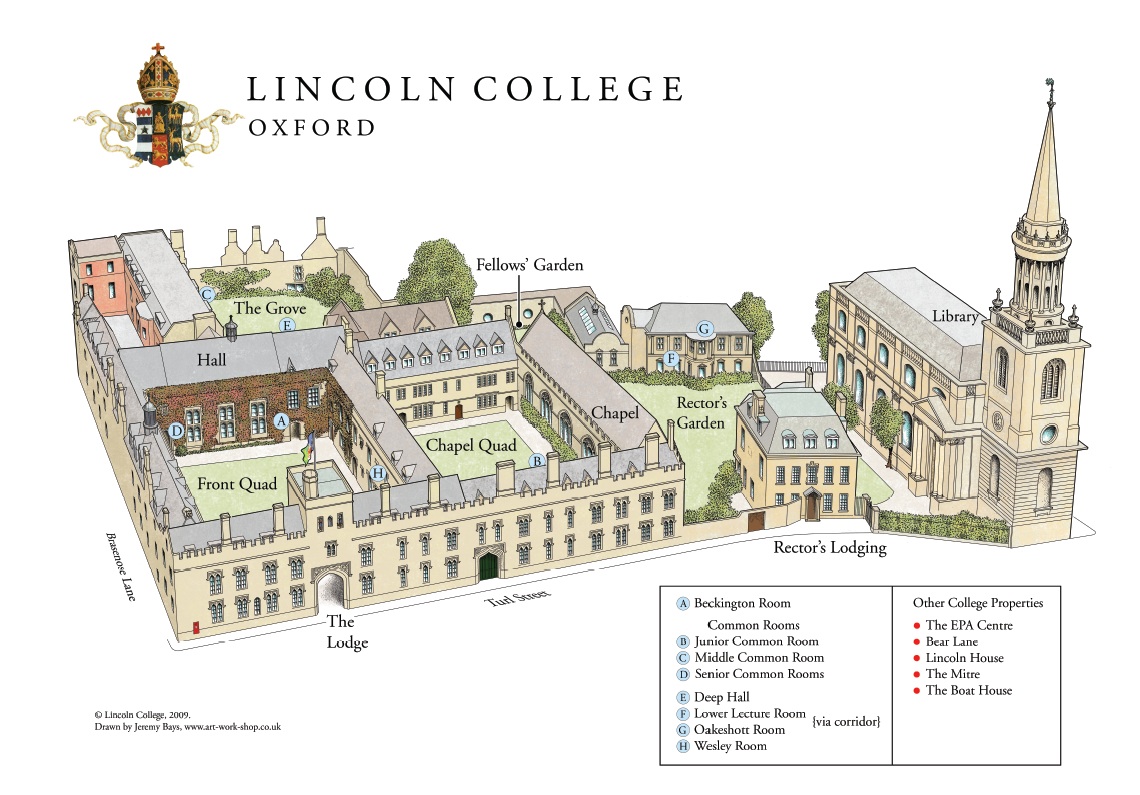

There is one way which will help solve 99% of all your problems. It’s so obvious that I hardly dare mention it for it could seem so boring – but it really does work. And it is, form a choir committee! In my 18 years at Blackburn Cathedral and my 16 years in the University town of Princeton, NJ, I was blessed by committees.

At Blackburn Cathedral I chaired a committee of choirmen. It comprised a secretary, treasurer and one representative from each of the voice parts – alto, tenor and bass. We met monthly and discussed and solved every problem which arose, and we also planned outings and other special events.

I even had a committee of the older children. We also met once a month, discussed how the other children were doing and what we could do to help them sing even better. The giving of this responsibility to those choir prefects meant that they, in their turn, tried even harder, for they were now part of the leadership of the whole choir. They were wonderful role models.

At Princeton I had a committee of choir parents. After consultation with my Rector I found it better to choose a separate chairman rather than myself. This person needed to agree to chair the committee for not more than two years, for we wanted someone who was much in demand, who was a leader in other fields, and who had the best interests of the choir at heart. We two met regularly to discuss future business, and she (it was usually a choir mother) was the sort of person whose advice I could ask and from whose insights I could benefit. Read all about this in my Immediately Practical Tips pp 166-177. I could not have fulfilled my vocation in that demanding place without such strong leaders to help and advise me.

I also learned how to have a constructive one-on-one meeting with a ‘difficult’ choir parent. (That’s also written up fully in my Immediately Practical Tips, pp. 260-261.) What do you want the outcome of your meeting to be? To prove that you are right? If so, that means that you will prove the other person wrong. No, the outcome for which you should aim is a better relationship between the two of you, and there’s a simple way to encourage this. Your meeting should begin by your saying genuinely appreciative things about this person and her family; how much they mean to you personally and also to the choir. That way you will enable that person to ‘hear’ what you are saying. And then, gently, lead on to address the problem area.

A few final tips:

1. Never put anything in writing to anyone that you would not want printed on the front page of your local newspaper. That, in practice, means don’t put anything controversial or critical into writing. Instead, think about the situation for at least 24 hours, and see how you can begin to turn it from being destructive (‘Why are you making my life so difficult?’) to constructive, (‘I so admire your energy, and wonder how your gifts could help not only your own children but also the whole choir.’) It is better to be kind rather than to be right.

2. If a difficult person phones you, never begin to argue, for you are both on your ‘home territory’ and therefore you could say things which you would regret. Instead, ask if you could fix a time when you could discuss the problem face to face.

3. Love your singers – or (if you prefer it) – show them courteous respect. Send birthday cards to the children and anniversary cards to your adults. Be the first to arrive for choir practice so that you can welcome each singer, and be the last to leave, so that you can chat with those who want to talk with you. Show your pastoral concern for your singers, both collectively and individually by following up absences immediately with a phone call, (‘We all missed you tonight; is everything all right?’).

The spirit of your choir is an accurate reflection of your own personality. So if there’s something which needs changing, you know where to begin!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013

JB's books may be found on the internet - and especially on Amazon.