How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

8. Expression

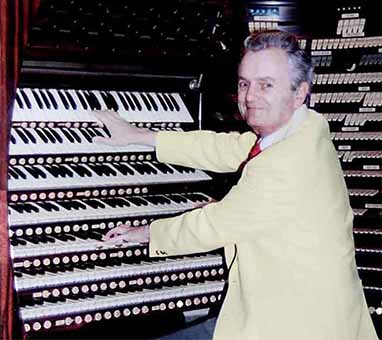

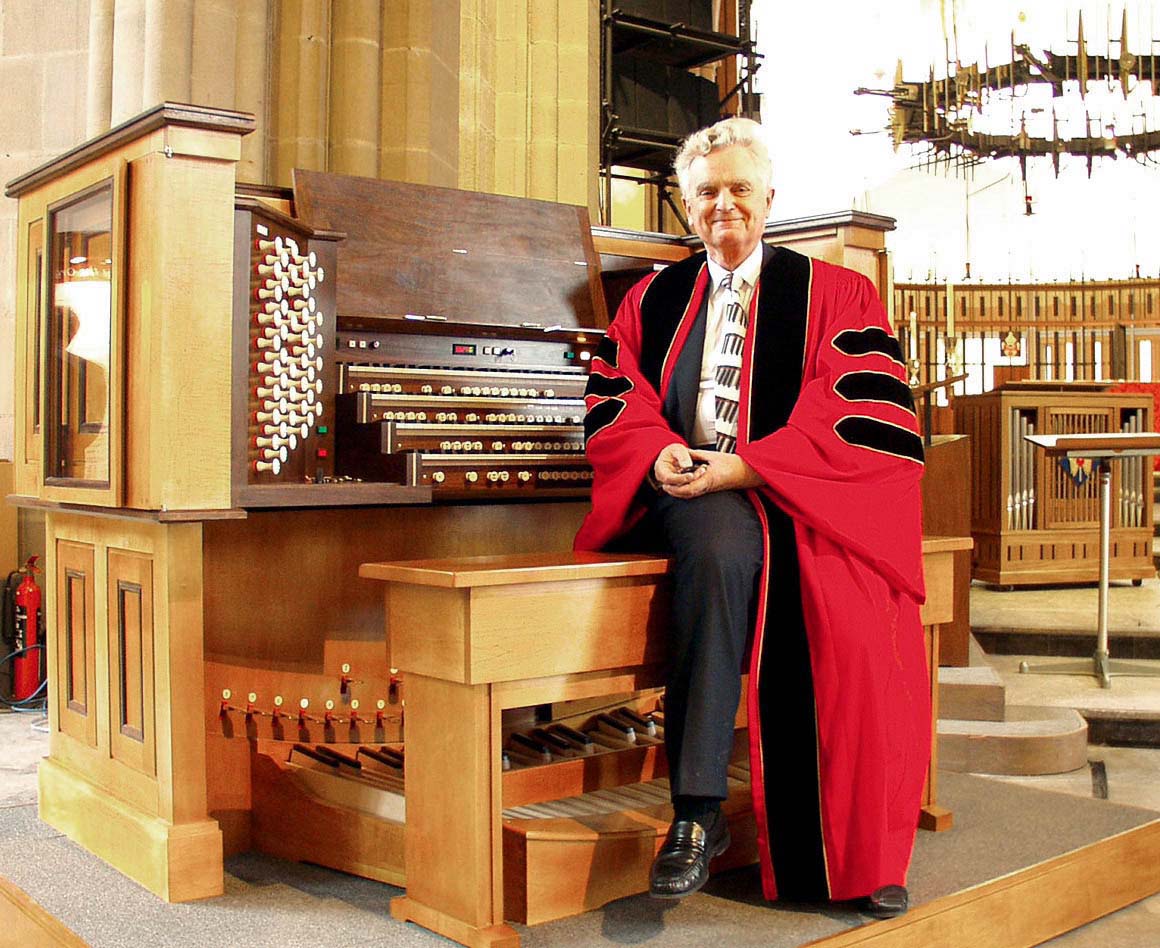

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

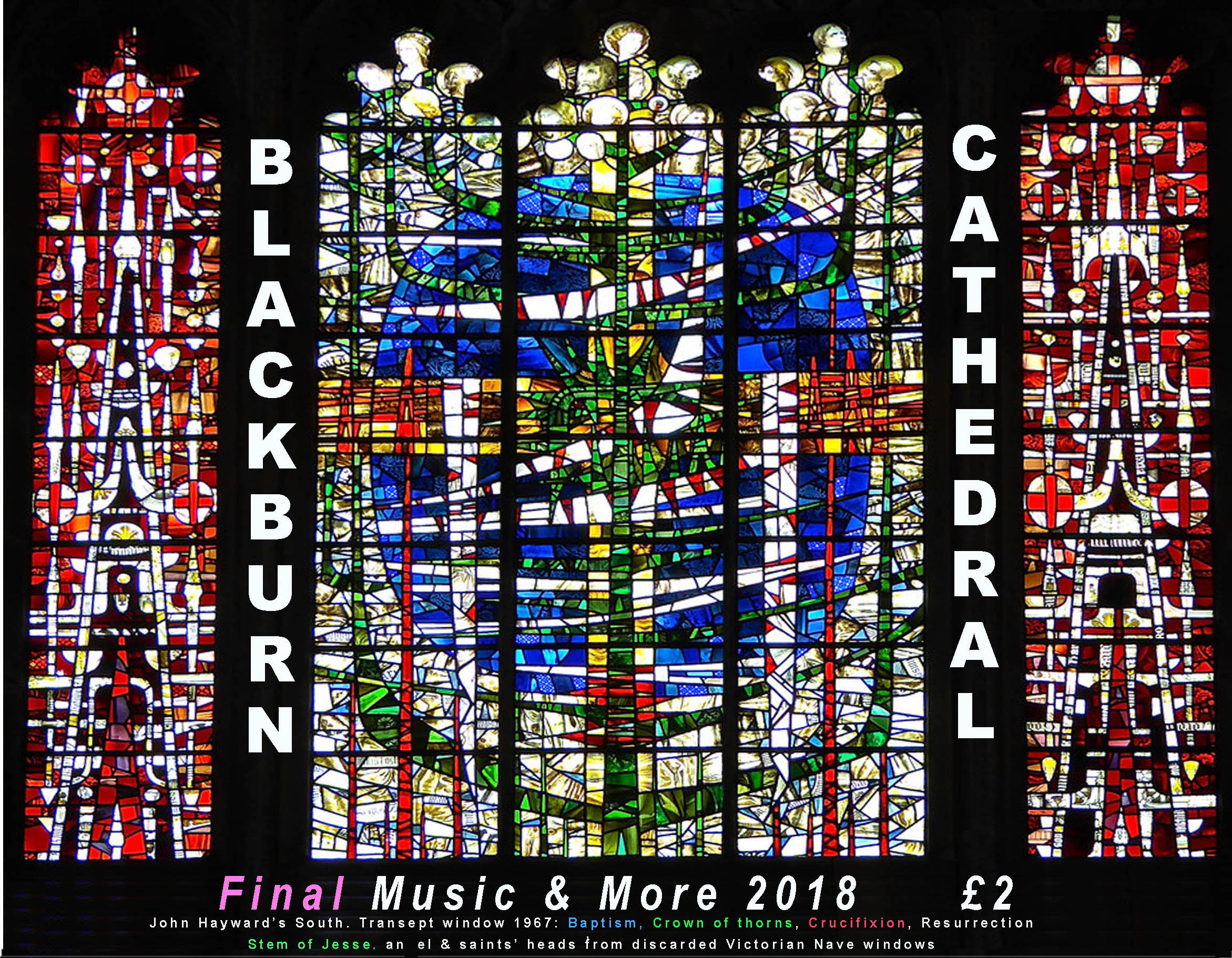

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

FORWARD MOVEMENT AND HIDDEN EXPRESSION

![]()

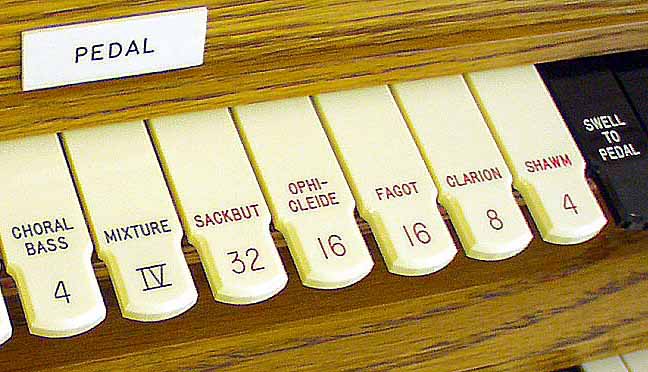

An essential essence of all music, be it Beethoven’s 9th or the simplest hymn tune, is forward movement. But it is the ingredient that is often lacking in so many of our performances, be they sung or played. For example, some organists seem to think in terms of playing notes without realizing that each one must be perceived as part of an ongoing phrase or sentence.

Plonk Plonk Plonk Plonk

Such playing can be likened to reading words letter by letter, or reading sentences word by word. Each only makes sense when they are related to each other in a continuous sweep.

And so if music is to make sense it too must have forward movement so that the notes move from one to the next in a continual onward flow – rather like water flowing in a gently moving stream.

Flow forward Flow forward Flow forward Flow forward

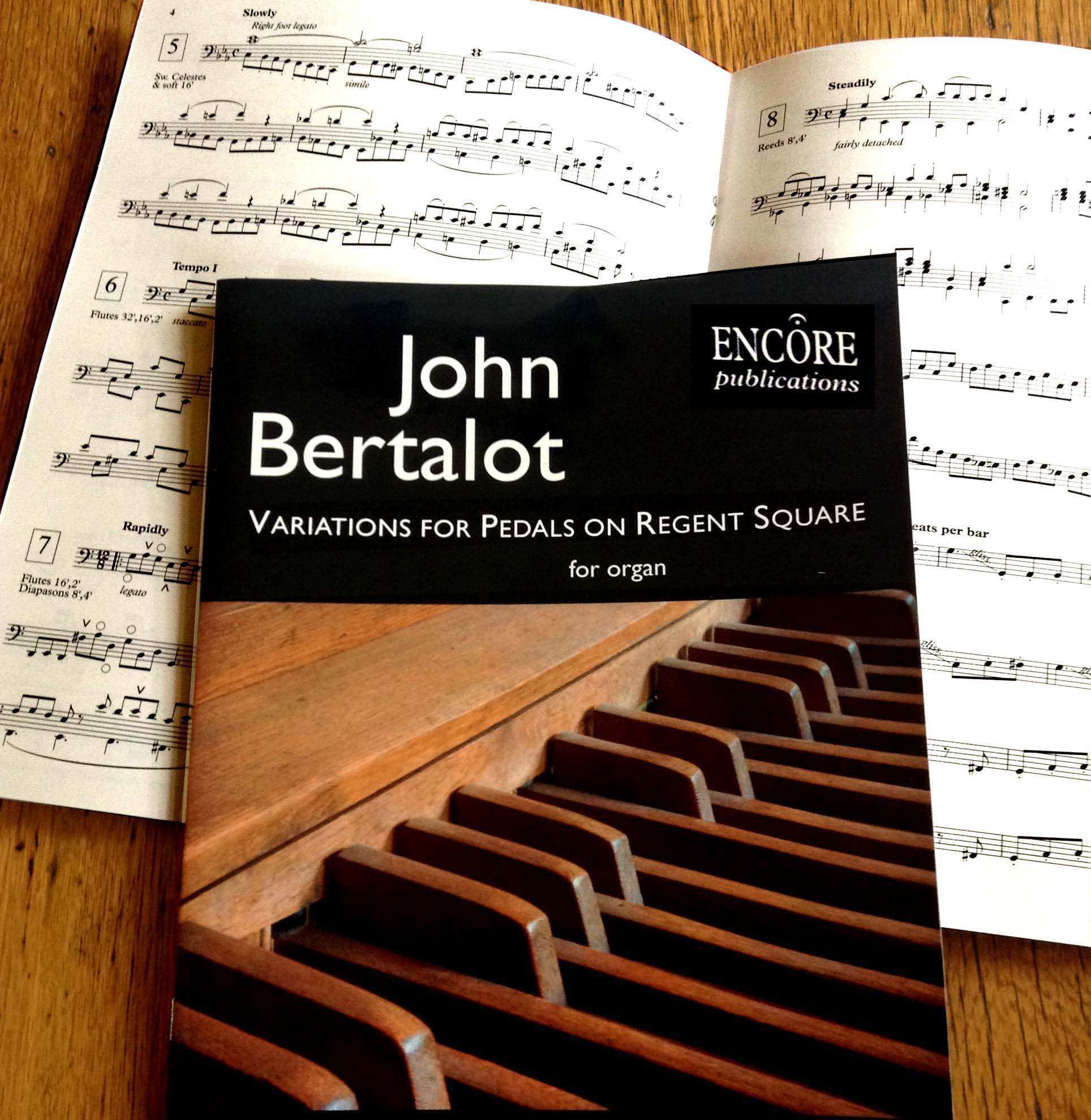

![]()

This is difficult to explain in writing; perhaps it can be more easily understood when thinking about the flow of words in a well-known quotation:

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

To bring this phrase to life one needs to stress the words ‘not’ and ‘that’.

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

But Shakespeare didn’t underline those two words to make that phrase meaningful. He expected his actors to add the expression.

It’s the same with music. The composer expects us, the choirmasters, to show our choirs what expression should be added to bring out the meaning of the words

and the beauty of the music.

But there’s more. That one line can represent a short phrase of music. But so much music is made up of long phrases, and we choirmasters need to help our choirs feel their expressive growth and decay.

Look at the compete quotation (say it out loud) and you’ll discover that there is an inevitable forward flow to the words which leads right up to the word ‘end’.

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outRAGEous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And (slight pause) by opposing (slightly longer pause) END them?

This need for forward movement and added expression is applicable to almost all music. (Elgar is an exception, for he included every nuance of expression he wanted. Other composers expect us to add our musicianship to theirs to bring their music to life.)

Has this sown a LIVE thought in your mind which you will pass on to your choir?

LET THE MEANING OF WORDS INSPIRE YOU

And so let the words inspire you to add expression, especially where no expression is marked. Speak this phrase out loud (with the rhythm of the tune Rockingham – i.e. two beats on ‘I’ etc.): When I survey the wondrous cross. Can you feel the forward flow of a crescendo right through to the first syllable of wondrous? If so, that’s how your choir should sing these words, even though no expression has been marked.

When I survey the WONdrous cross![]()

(By the way, some of your singers will take a breath after ‘survey’. Don’t let them; you can’t make a crescendo when you’re taking a breath!)

SING IN 'CURVES'

Adding such expressive crescendos and diminuendos, especially when the composer has not included them, will bring your music-making to life as never before. I used to remind my choirs in the USA to sing in ‘curves’ – with the dynamics rising and falling in gently expressive phrases. Music is never meant to be sung in straight lines.

If your choir sings hymns during the administration of communion, let them sing in curves as the words and music demand. Ask them to read a line of words and tell you where the important syllables come and, therefore, what they should do to bring them to life. (Answer: Crescendo towards them and diminuendo away from them.)

You need only rehearse this in detail for one verse and, after they’ve achieved that to your and their satisfaction, ask them to look at the next verse for a few seconds to work out where the important syllables come, and then to sing it unaccompanied. You and they will be thrilled at the way the music and the words come alive.

CRESCENDO TOWARDS IMPORTANT SYLLABLES

This is especially true of the music of Howells where every long note demands either a slow crescendo or an equally beautiful diminuendo.

Like as the hart desireth the waterbrooks...![]()

But there’s still more.

Every crescendo should work towards a culminating note or syllable. (Let me say that again: Every crescendo should work towards a culminating note or syllable.) One should not just ‘crescendo’ – but crescendo towards a certain note or a certain syllable. In the phrase above the climax is the first syllable of ‘waterbrooks’. And so this phrase will be transformed:

Like as the hart desireth the WATerbrooks![]()

But there’s even more! The next phrase of words is the culmination of the first phrase:

So longeth my soul after THEE, O God.

So the word ‘Thee’ is the climax of those first two expressive phrases, and the final word, ‘God’ will be sung with a controlled diminuendo. And by realising that we suddenly find ourselves thinking in long lines – even for a whole page. And once we do that, we really will begin to inspire our choirs to sing with creative expression. They will be bringing to life the meaning of the words and the beauty of the music.

By the way, let your diminuendos also be sung with forward movement.

![]()

So many choirs sing diminuendos as though they were pricked balloons – retreating. No! A forward-moving diminuendo can be even more thrilling than a forward moving crescendo. And when you reach the final note of an anthem, especially if it is loud, keep moving forward right through that long note – making a slight crescendo until the final cut-off. That will make the culmination of that anthem almost unbearably thrilling.

HAS THIS MADE SENSE TO YOU? If so, Try it!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013