How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

9. Khonnssonnanntts

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

KHONNSSONNANNTTSS

Have you noticed, when you are listening to a choir or choral society singing a work which you don’t know, that you can’t understand the words they’re singing? That’s because their consonants aren’t as crisp as they should be. But when you do know the work, the words seem to be much clearer because we supply the missing consonants in our minds without realising it. The vowels may be clear, but one needs both vowels and consonants to make oneself understood

I recently took a rather good parish church choir for a rehearsal; their tone was good, the notes were pretty accurate, but their consonants – oh dear – they were just not there! This may be true of many other choirs. I find with my own village church choir (which is made up of adults who are not necessarily in the first flush of youth) that I have to encourage them every week to make the effort to pronounce consonants – for they weren’t brought up to make this extra effort.

EFFORT!

What about your choir? Do they realize that in order to sing consonants clearly they have to make a conscious effort to focus on them? Clarity of diction has to be ‘larger than life’ – rather like actors on a stage. Their make-up reinforces their facial features: their eyes have to be bluer, their lips redder and their bone structure slightly emphasized in order for them to look natural at a distance.

OVER-EMPHASIZE

In order for your choir’s enunciation to sound natural at a distance, they need to over-emphasize slightly their consonants. Singing words in the same way in which they speak them is not enough.

The letter ‘D’ is the consonant which is nearly always missing. This can lead to making nonsense of some of the phrases they sing so frequently. For example, in the Gloria Patri, one can hear, ’The Father ran to the Son’. In the Magnificat we can advertise sweets: ‘Abraham aniseed for ever!’ And the beginning of the Nunc Dimittis is nonsensical without Ds and Ts: ‘Law now lettuce…’.

BRISK WARM-UPS

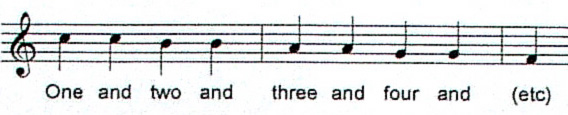

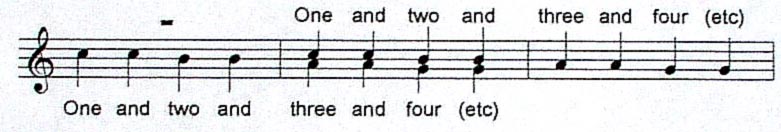

I’ve found that a brisk warm-up of a few scales sung, unaccompanied, to the words, ‘One and two and three and four…’ focusses the choir’s attention on consonants immediately.

But beware, they’ll try getting away with, ‘One ‘n two, ‘n three ‘n four…’ so ask them to overemphasize the ‘Ds’. ‘One ander two ander three ander four…’ They’ll suddenly discover that it requires extra physical effort as well as mental effort to sing those Ds.

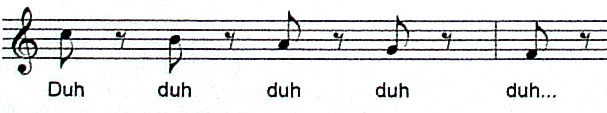

Show them that the letter ‘D’ can be sung to a note. Have them sing a downwards scale staccato to the letter ‘D’. ‘Duh, duh, duh, duh…

Once they’ve achieved this to your and their satisfaction, ask them to lighten the ‘er’ sound to, ‘One and(uh) two and(uh) three and(uh) four…’. Spend a little time with this: have them sing several scales, which rise a semitone each time. My choir loves to sing scales in canon – one side starting after the other side has begun.

They like singing scales in four-part canon even better: sopranos leading, then altos, then tenors and then basses. This really makes them try harder! (And that’s the great secret of running a fruitful rehearsal – encouraging your singers to try harder!)

They’ll also discover that it’s not only Ds which need more effort but also almost every other consonant:

Forty days and(uh) forty nights thou wast(uh) fasting in(uh) the wild(uh)

All glory laud(uh) and(uh) honour . . .

O sacred(uh) head(uh), surrounded(uh) by crown . . .

When a ‘D’ is the final consonant of the last word of a phrase, make sure that your choristers sing the final ‘D’ on the same note as the vowel. Some singers will tend to change pitch on the ‘D’:

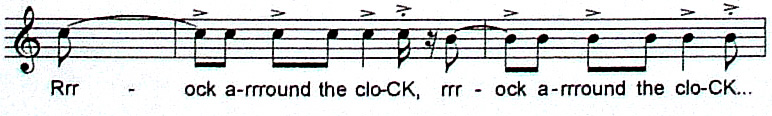

‘Rs’ often need to be rolled. You’ll find that some choristers can do this easily – others may have to work at it. So ask them to sing a scale to a rhythmically monotoned Rock around the clock, and to sing the rolled ‘R’ before the beat, so that the consonant comes on the beat:

(It looks complicated, but if you sing it for them first with four strong beats per bar they’ll follow your lead.)

DOING IT IN PRACTICE

Return to the anthem or hymn that you were rehearsing and ask them to speak the words very clearly, paying particular attention to the consonants. ‘To his(uh) feet(uh) thy trrribute(uh) brring, Rrransomed(uh), healed(uh), rrrestored(uh), forgiven…’. They’ll find that, in order to enunciate clearly, they’ll have to place the consonants at the front of their mouths. This may be a new experience for them.

By the way, make sure that crisp ‘Ts’ are not turned into careless ‘CHs’: ‘Taking Tuesday trains to Tooting.’ Not ‘Tiking Choosdee chrains ter Tewting.’

Then ask them to sing ‘To his feet…’ with equal precision. Ask one side of your choir to sing that line or phrase, and ask the other side if they really can hear the consonants. Then change over. That’s always a good way to raise standards, for you are asking your choir to criticise themselves constructively. The element of competition works as well for adults as it does for children.

You’ll find that they will enjoy this. In other words, the singing of really well-focussed consonants can become a fun challenge.

I’ve found that when I ask my choir, ‘Which letter did you miss out on that line?’ they will invariably tell me and then sing it clearly. In other words, it’s our task as choirmasters to encourage our singers to correct their own shortcomings by asking them the right question. But we’ll have to do it every week!

Does this make sense to you? If so, Try it!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013