How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

27 How can I encourage children to sing?

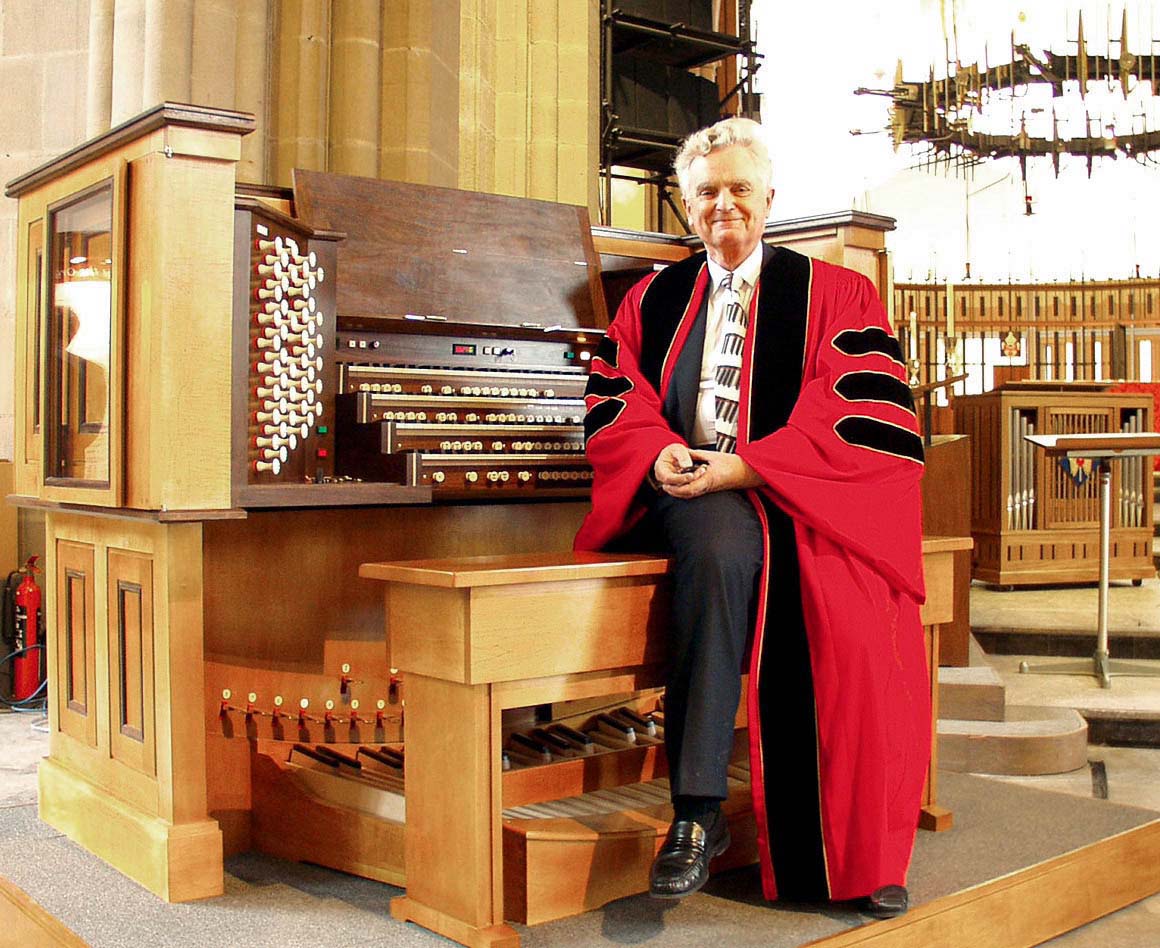

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

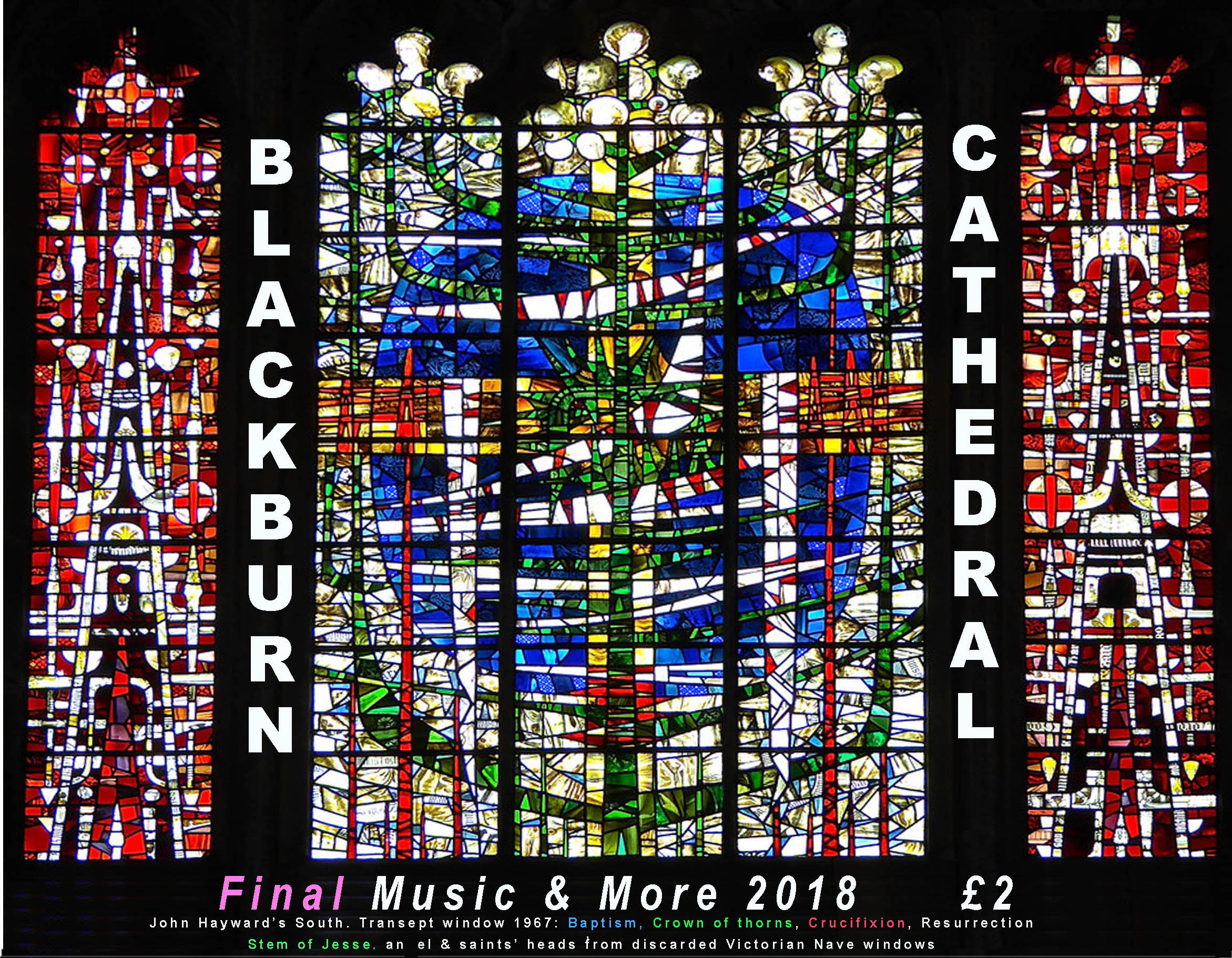

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

The third main question I was asked when I led a workshop for diocesan choirmasters at Hereford Cathedral was, How can I encourage children to sing?

Would I be right in saying that, if you have children in your choir who sing alongside adults, their contribution to the choir is primarily decorative? You may answer, ‘But I don’t expect them to take a lead in singing; the adults do that.’ That defines the problem, for what you expect is what you get.

The Hereford choirmasters were asking essentially, ‘How can the children in my choir begin to take a lead in our singing, and how can I encourage them to stay on into their teenage years?’ The second question will be answered when your children begin to take a lead, for they will know that their presence is valuable to your choir, because they will have accepted a large measure of responsibility for the choir’s achievements.

I recently led a rehearsal for a Lancashire church choir; they were made up of keen adults, and there were also some children. I quickly discovered that the children were unable to concentrate even for a short time; they didn’t stand up straight and they sang half-heartedly. Their choirmaster told me that they would pick up singing skills as they grew older. But as he had been choirmaster of that church for many years I wondered why there were no teenagers present, for if they had ‘picked up’ singing skills when they were younger, they should have been there now. But they weren’t. Therefore his current children were not picking up singing skills even though he thought they were. What should he have done?

Essentially, the children were out of their depth and quickly become bored.

Another question: why should children come to your church to sing hymns and try to sing the occasional anthem when they could be enjoying themselves in so many other ways at home, or by going out with their friends? The answer, surely, is to make it worth their while to give up an hour every week to be with you. And how do you do that?

Answer: give them a lot of individual attention. It comes back to the dictum I’ve repeated many times: if you want your choir to work harder for you, you must work harder for them. And so, are you prepared to work harder with and for your children? If you are, then continue reading, for there are five things you need to do.

1. When you first meet a child who wants to join your choir (or whose parents want them to join!) you need to give that child ten minutes of your time, one-on-one. The word I’m trying to avoid is ‘audition’. That word usually implies that you’re trying to find out if the child is good enough to join your choir. No!

When I auditioned children for my volunteer choirs in the USA and here in England I spent ten minutes showing that child that he or she could achieve far more with me than they had ever done before. In other words, being with me (and this is not being big-headed, but purely practical – for as a choirmaster I believe I know what I’m doing) … being with me is an adventurous musical experience for that child. He or she feels, ‘I didn’t know I was so clever. Being with this man is exciting and fun. I want to come again.’

So, what did I do?

(a) I asked the child (let’s call him William) all about himself. What school William attends, what he enjoys doing, does he play any sport and does he sing in the school choir. In other words, before I can expect him to show interest in my choir, I must genuinely show interest in him.

(b) Then I play a note (middle G) and ask him to sing it to me unaccompanied. (Don’t play the note with him; this is his first little challenge.) Usually this is not good, and so I ask him, ‘Should your mouth be open or closed when you sing?’ He gives the right answer, and so he does it again.

But he has no conception what an open mouth should be, so I ask him to put two fingers in his mouth so that he can show himself. ‘Could you put three fingers in? Let’s try it again.’ In other words he is showing me what he should do. That is the secret of how these ten minutes should be spent. If I tell him what to do, that’s boring; but if he tells me and succeeds (by my asking him the right questions), that’s exciting!

(c) Then I go on to ask him if he could sing that note for four beats whilst I count on my fingers – coming off on the count of five. (And I demonstrate this for him.) ‘How was that? Was your mouth open or closed?’ Then he counts on his fingers. (I’ve written about this in detail in my second book, Immediately Practical Tips for choral directors.

(d) And so we go on, gradually increasing the number of beats and raising the pitch of the notes, so that William finds he can achieve something he’s never done before: i.e. singing with an open mouth, singing reasonably high notes (not too high at this stage – perhaps up to C), and being introduced to the concept of rhythm, even though he doesn’t realise it.

(e) Then he has a go singing a verse of a hymn that he knows - and, again, I ask him to tell me what he could do better: How is your mouth? Which letter needs to be clearer in that line? and so on.

But most of all he finds that he’s being challenged the whole time to do better, not because I told him that what he attempted wasn’t good enough, but because he told me that he could do it better. And he succeeded in every challenge. So those ten minutes defined what it was like to be in my choir – a continual challenge to aim for new heights, and to reach them week after week after week.

2. Have an encouraging word with William’s parents who brought him. But don’t say ‘He must join the choir,’ but, ‘Would you like William to come along to our practice next week to see what it’s like?’ That way William will not feel trapped, for he doesn’t know what is involved in being in your choir.

3. When William comes to your practice next week give him a few challenges to meet so that he feels that his time was very well spent.

Could he sing the first line of this hymn?

What letter did he miss out in that word?

Could he sing that line in one breath?

Show me how you should stand when you’re singing.

Which feels more comfortable, standing straight or standing sloppily?

In other words, doing something right feels better than doing something badly. He wants to feel good about what he does, and you’re there to help him. And so William will want to come to your next practice, and the one after that until he eventually asks you if he could join your choir!

4. The practice that William attends should be for children only. Ideally the newer children should have a practice to themselves, for the older children will have acquired greater skills. The more experienced children will want higher challenges so they need to be rehearsed on their own. If you can give, say, an extra hour to your children before your adult practice, that would be so helpful; 30 minutes for the younger children and 30 minutes for the older ones. The older children could stay for the first half hour of your full choir practice when hymns and other easy music could be rehearsed.

5. But above all I have found that teaching children to read music is the greatest secret in creating and keeping a successful children’s choir and for enabling children to take a lead amongst adult singers. It’s so simple to teach this skill; all it requires is

(a) endless patience,

(b) teaching one small skill at a time,

(c) repeating this week what was taught last week to make sure that that skill is thoroughly understood,

(d) and putting that skill into practice during your rehearsal, by asking the right questions. ‘What is the name of that note, is it G or A? How many beats should you sing it for, two or three? Let’s do it. Was that wholly right? Let’s try it again…’

Always teach by asking questions, for children need to talk. It doesn’t matter if the question is simple – ‘Who is standing well? Did we all start together?’ If you continually tell them what to do, they will immediately turn off and you will have lost them. But by asking questions – one every 15 seconds or so – you will show them how to concentrate for longer and longer periods, and this will help them in all sorts of ways, not least with their school work, and this will please their parents.

I suggest that William isn’t given a choir robe until he’s earned it. Give him a very clear aim what he should achieve to earn his robe. Then he’ll value it more highly. The Royal School of Church Music has an admirable scheme for training children and other singers, which is called Voice for Life. ‘Google’ Voice for Life to find out all about it.

I’ve put these purely practical principles into practice throughout my life, and they really work. Adults tell me how much their years in my choirs, when they were children and teenagers, meant to them. This makes it all worthwhile. Try it!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013