How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

28 Major Musical Influences in my life. No.1

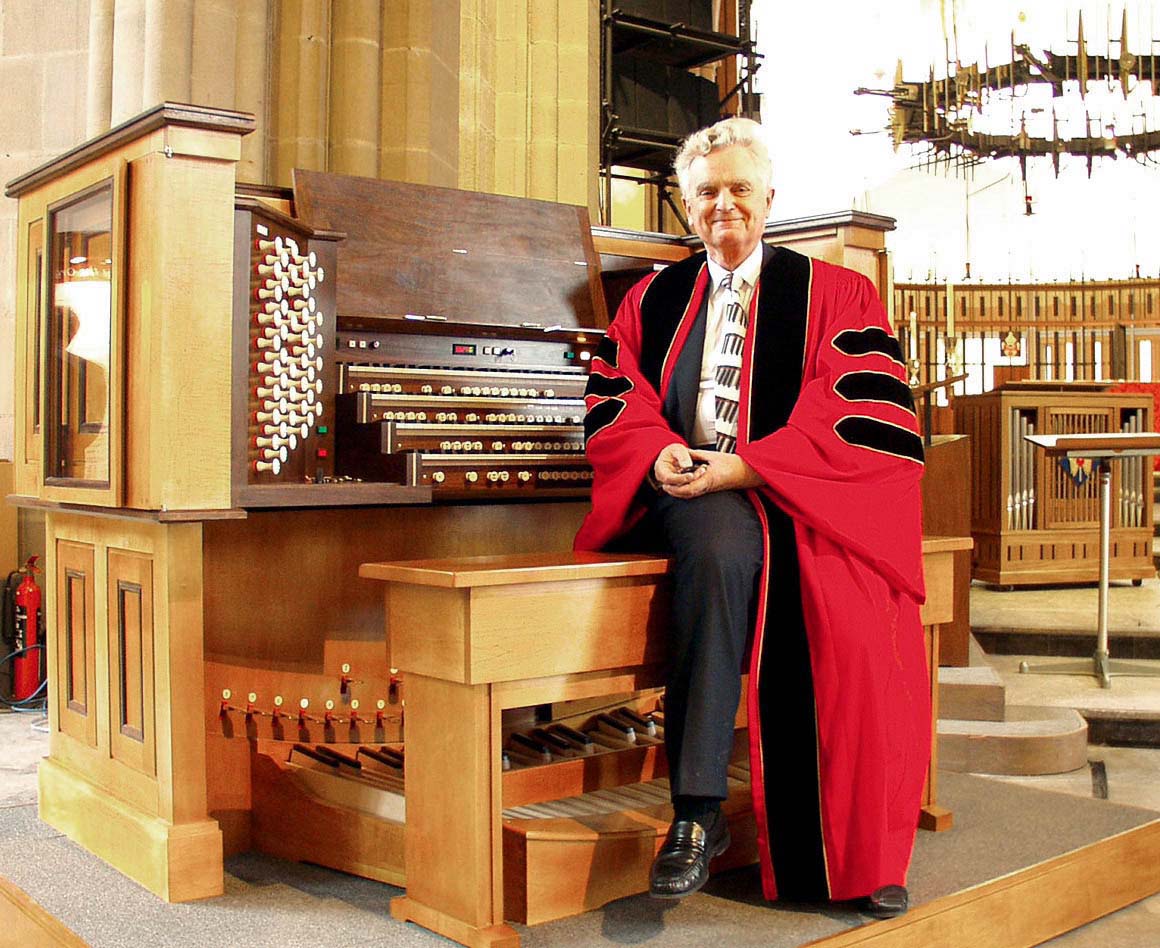

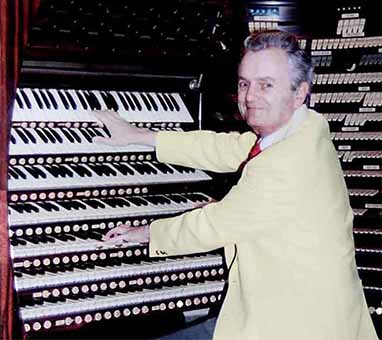

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

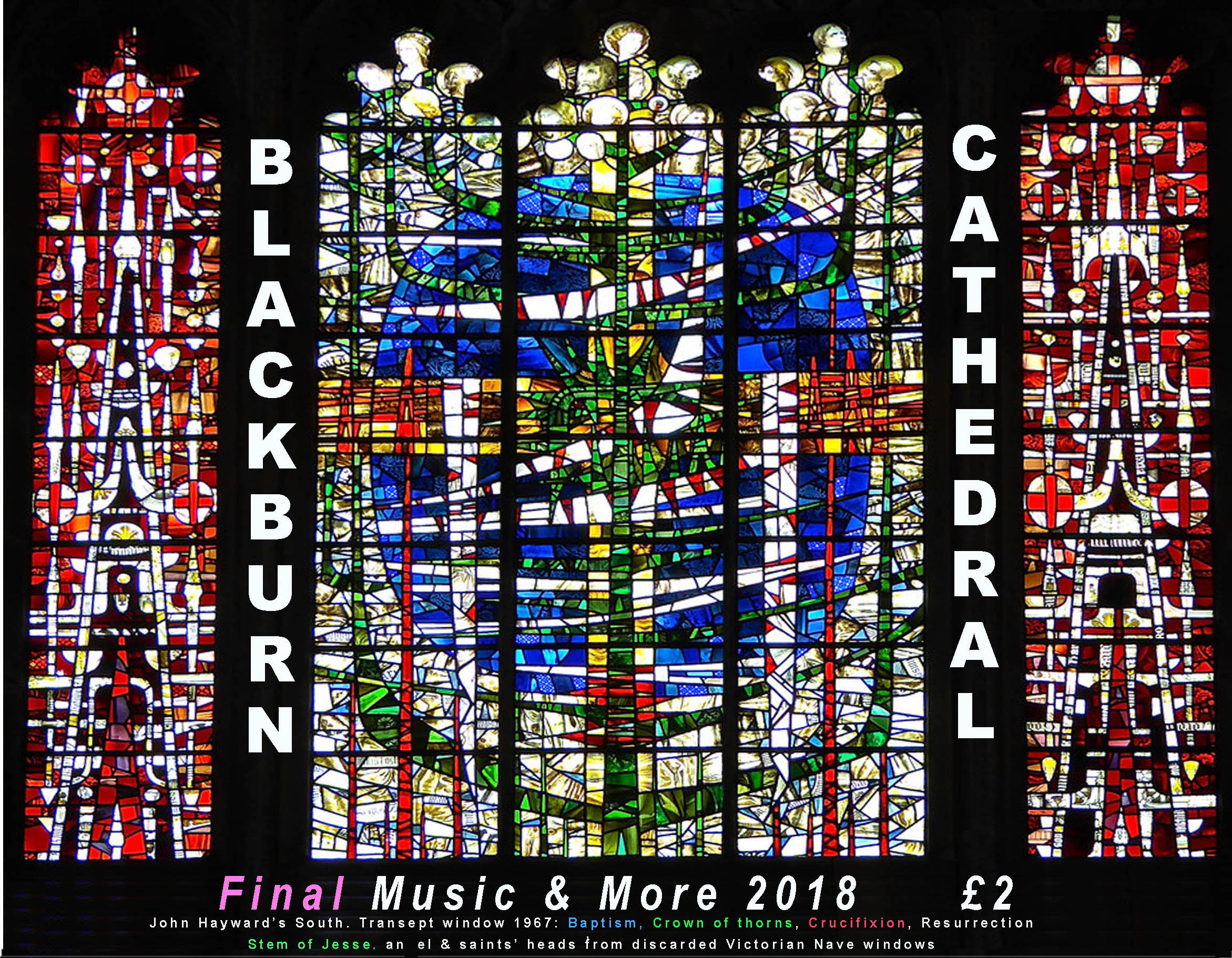

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

Have you met musicians whose gifts and commitment have inspired you to become a better musician yourself? Almost everything I’ve learnt has come from watching others. So I share some of these immediately inspirational (and sometimes constructively traumatic) experiences with you. They’ve changed my choirtraining life; may they change yours.

Number 1

Walter S. Vale

Dr. Vale was, for 32 years from 1907, the outstanding Director of Music at All Saints’ Church, Margaret Street, London. He had one of the finest church choirs in this country and wrote a book about choirtraining which I bought when I was a student. The sentence which stands out for me is, 'Soft singing cures a host of faults', for it has been a mainstay of my choirtraining throughout my life. How?

1. If you want your choir to blend (and not too many church choirs do blend!) ask them to sing a chord softly in harmony (perhaps the first chord of a hymn) to the vowel ‘Ee’, and to sustain it for about 15 seconds or more. Tell them that they need to listen to each other: can they hear the person next to them – can they hear the singers on the other side of the choir – can they hear how their own voice fits into the ensemble? Ask one side to sing whilst the other side listens, then they will discover for themselves whether or not they are blending.

Having sung that chord and achieved a sense of corporate blend, ask your choir to sing the whole hymn tune softly in harmony to a vowel. ‘Ah’ is very useful, for your singers will need to drop their jaws and open the backs of their throats. Let the singing be really soft, for soft singing does cure a host of faults.

2 But don’t confuse soft singing with lethargic singing. When some choirs sing softly they immediately go into a lack-lustre mode. This need to sing softly but positively occurs halfway through Stainer’s ‘God so loved the world’, where he marks these words to be sung softly: ‘But that the world through Him might be sav-ed.’ Now this is the very heart of the Gospel – the heart of the Good News – and so it should be sung joyfully. How can you sing softly and yet joyfully? Answer: ask your choir to whisper these words with energy, so that they can be understood by someone at the back of the church.

Ask one of your singers to go to the back of the church to see if she can hear what the choir is whispering. This will help the choir to discover whether or not they have achieved what you’re asking of them. They may have to try this several times before you and they are satisfied.

And then ask them to sing that phrase with the same alert state of mind. They’ll find that their soft singing comes most wonderfully alive.

A similar soft passage, which could err into a dreary mode, is the beginning of Wesley’s ‘Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ’. This, again, is joyful, but it is so often sung gloomily! Another is the beginning of Howells’ Collegium Regale Magnificat, where the trebles should sing with ethereal joy – ‘My soul doth magnify the Lord’. Many choirs sing this passage as though the words were anything but joyful.

3. Soft singing also helps your choir to sing in tune.

4 And there’s one further aim for soft singing: and that is how to sing music which is marked PPP. Very few choirs indeed can sing a PPP passage really softly. Many choirs come down to an MF-minus, but that’s about as far as it goes. There’s nothing quite so magical, when the music calls for it, as a passage that is sung so softly that it’s almost inaudible. But this has to be sung with terrific concentration, energy and purpose, with no hint of laziness. Some choirs sing hymns during the administration of communion. You might like to try singing ‘Be still and know that I am God’, or some similar hymn, starting each verse PPP, then gradually crescendoing.

Soft singing really does cure a host of faults, and it can be so rewarding.

Number 2

Martin J. R. How

1 Martin has been one of the most inspirational choirmasters I have ever met. When we were both much younger he was Headquarters Choirmaster of the RSCM at Addington Palace, and he invited me, several times, to be a housemaster on his choristers’ courses. It was he who demonstrated how thrilling it was to teach children to sight-sing. He began by writing simple rhythms on a blackboard and asking the children to clap them. They enjoyed this to the full, and were therefore able to begin to tackle new music with a greater sense of confidence.

From this experience I discovered how keen children were to learn this skill, and so all the children in my choirs, both in the UK and USA, became skilled musicians. One is now a university professor of music and another is an internationally acclaimed orchestral conductor; others teach music in schools or lead the singing in choirs and choral societies, for all retain their skill to read music and therefore they can share it with others.

2 When I was organist of St. Matthew’s Church, Northampton, I invited Martin to lead a one-day course for local choristers. There were about 100 children in the church hall. I arrived late for his first rehearsal, and found him standing on a low platform in the middle of the children who were looking at him with a terrific sense of expectation. I looked round the hall to see where my own choristers were, and saw that their eyes were shining as they looked at Martin. ‘What is he doing?’ I wondered, for although my choristers tried hard for me, their eyes didn’t shine! I quickly discovered his secret.

He was asking simple questions every fifteen seconds or so.

Questions which most of the children could answer straight away, such as:

• Did we all start together? Yes Roger, you tell us…Let’s try it again.

• How many beats are there on that first note – two or three? Quite right, Mary.

• What letter didn’t I hear in the word ‘anD’?

• Where is there another word in that line which needs a clear ‘D’? Let’s try it.

• Let’s have this half of the choir singing that passage, and then the other half, to see who can sing it best!

Martin led his rehearsals terrific energy and enthusiasm, and this was fuelled by the energy and enthusiasm that the children were giving to him. I’d never experienced such a concentrated day of singing, and the children loved every minute of it. The spin-off to my choir by my choristers was amazing.

In the USA I was once asked to lead a practice for some not very talented children, which I wasn’t looking forward to. But I thought, ‘Let me pretend to be Martin How, to conduct the practice with energy, to ask simple questions every 15 seconds and to be really enthused by the music they are singing and by the way they sing it.’ And, do you know, it worked! Their eyes shone, and so did their singing.

There’s always a strong element of the choirmaster being ‘on stage’ when leading a practice. Try it for yourself.

Number 3

Dr. Gerald H. Knight

GHK was the legendary Director of the RSCM in the middle of the 20th Century, and I owe more to him than I can ever repay. It was largely through him that I was appointed to S. Matthew’s Church, Northampton, (I still have the letter in which he suggested that I should apply!) and it was he who invited me to lead six annual 2-week cathedral courses in the UK with hand-picked singers, and prestigious courses for choristers and choirmasters in the USA. But he also gave me two pieces of valuable practical advice:

1 ‘When you begin your new organist’s post, find out what your predecessor did and how he did it, and then do it better.’ That wasn’t easy, as the three musicians I succeeded (two in the UK and one in the USA) were of national and international stature. But I did find some things that I could do better, and so I quickly became accepted by the ‘old-timers’ in my respective choirs – and that was vitally important. And I learnt from the skills that my predecessors had exercised through their choirs which I had inherited, and therefore I grew in consequence.

2 ‘When you give a boy a piece of music to sing, he looks at the words and not at the notes.’ (That was in the days before girls were more warmly welcomed into church choirs.)

I confess that I didn’t believe what Dr. Knight told me – until I found through my own experience that it was true; true not only of boys and girls, but also of adults.

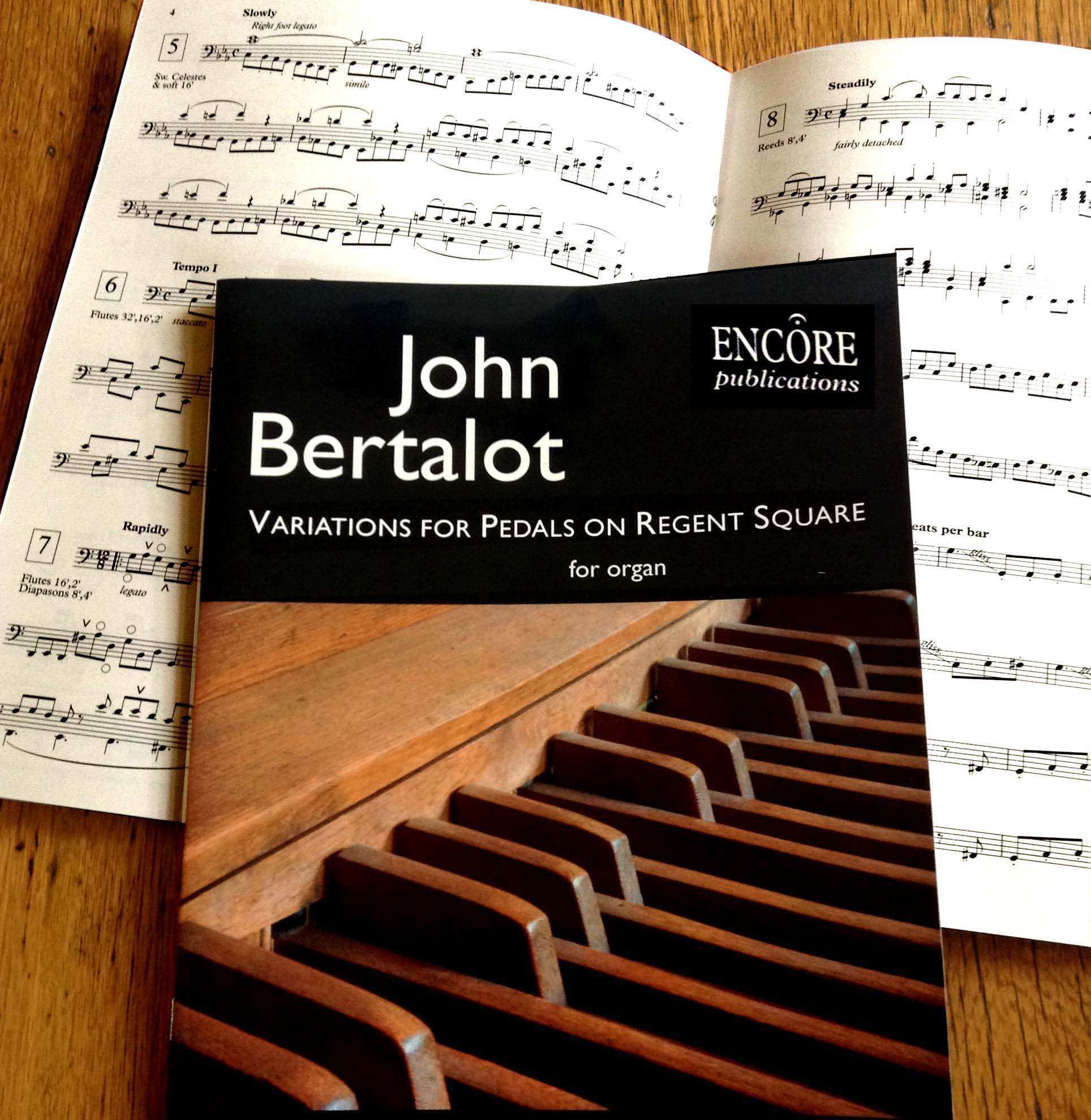

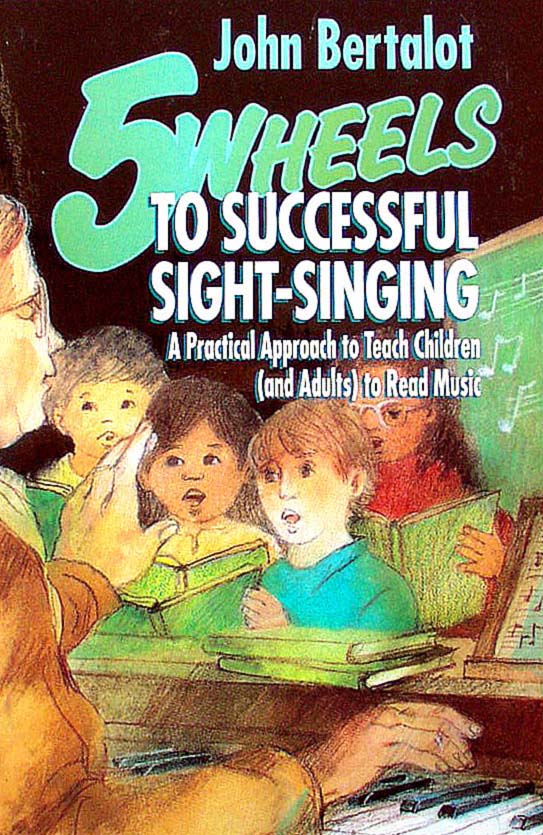

And so my own methods for teaching sight-singing continued to take shape, which has led to the publication of two sight-singing books – one for teaching children and the other for teaching adults.

And this skill has been one of the corner-stones of my life as a choirmaster, for once your singers can begin to read music, the leading of rehearsals becomes so much easier. One choirmaster who came to watch some of my rehearsals in the USA told me afterwards that she hadn’t realised that a choir can begin polishing new music straight away – there was no need to learn the notes, for the right notes were already being sung.

Number 4

Dr. Hubert Middleton

When I was a second-year student at Cambridge I joined a small class for lessons in composition. One week Dr. Middleton asked us to write a string quartet movement in the style of Mozart. As I was already an FRCO I thought I knew what I was doing, but when Dr. Middleton looked at my composition he let out a quiet Hrrump, which startled me. ‘Look at that cello part!’ he thundered gently,’ (I’d written a simple, undemanding cello part.) ‘Would you expect a young lady cellist from Girton College to come three miles into Cambridge on the bus with her cello on a wet Monday night to play thattttt? Give her something worthwhile to play!’

And from that traumatic experience I realised that if I wanted my choristers, be they adults or children, to leave the comfort of their homes to come to my practice room on a wet Monday night, I had to make it thoroughly worth their while. Not to play musical games (as some choirmasters mistakenly believe) but to work really hard so that they could achieve something positive, learn something new and so feel really glad that they had made the effort to be there.

And as a result of that never-to-be-forgotten lesson which I had learnt from Dr. Middleton when I was still a student over 50 years ago I have always had full choirstalls whatever the weather. The same can be true for you.

In my next article l share inspirational experiences I’ve learnt from Dr. Boris Ord, Fernando Germani, Sir Malcolm Sargent and more.

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013