Choir training can be so simple if you really know what you're doing!

31 LOOK AGAIN!

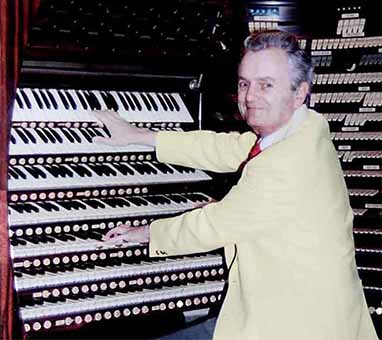

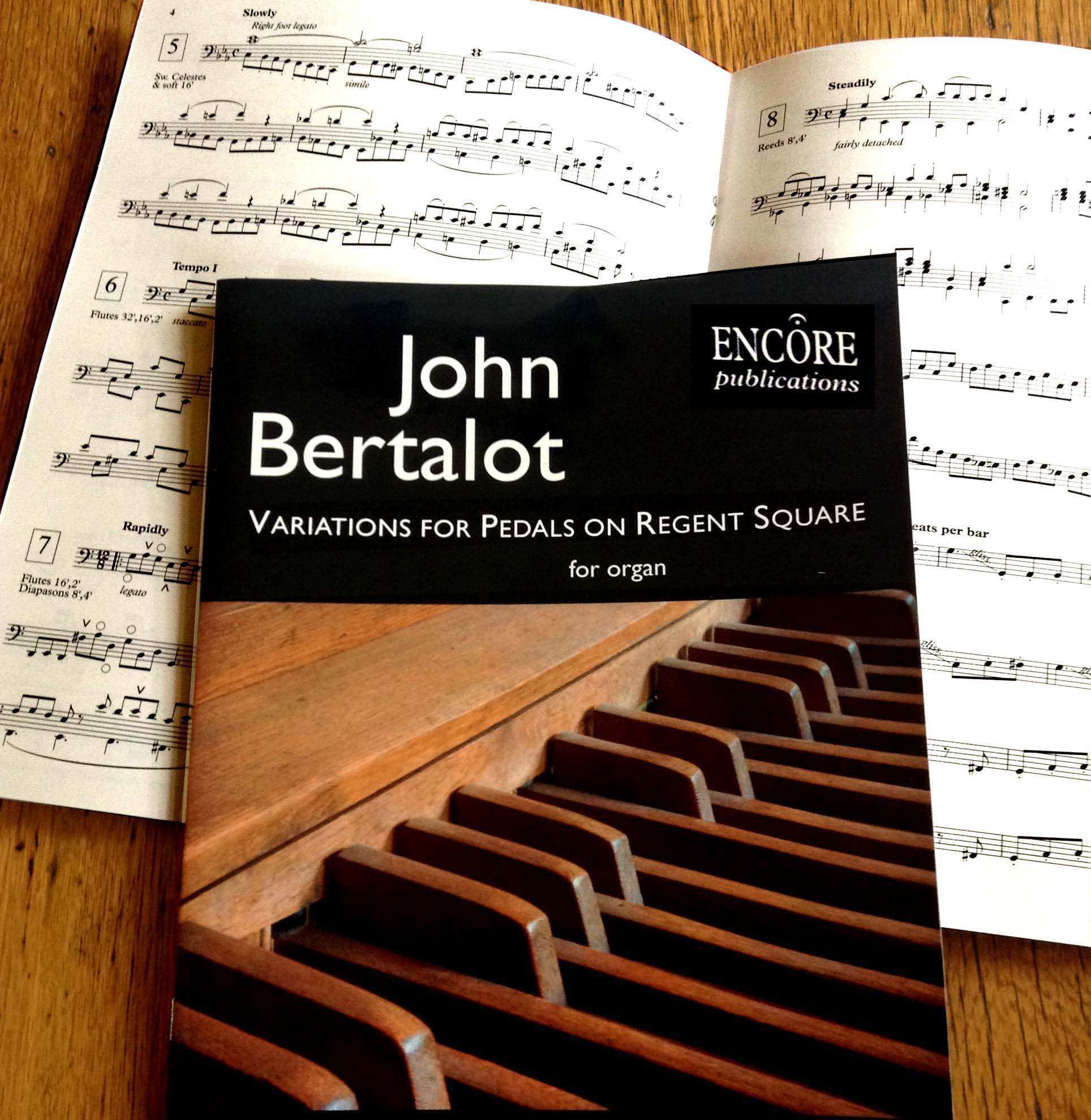

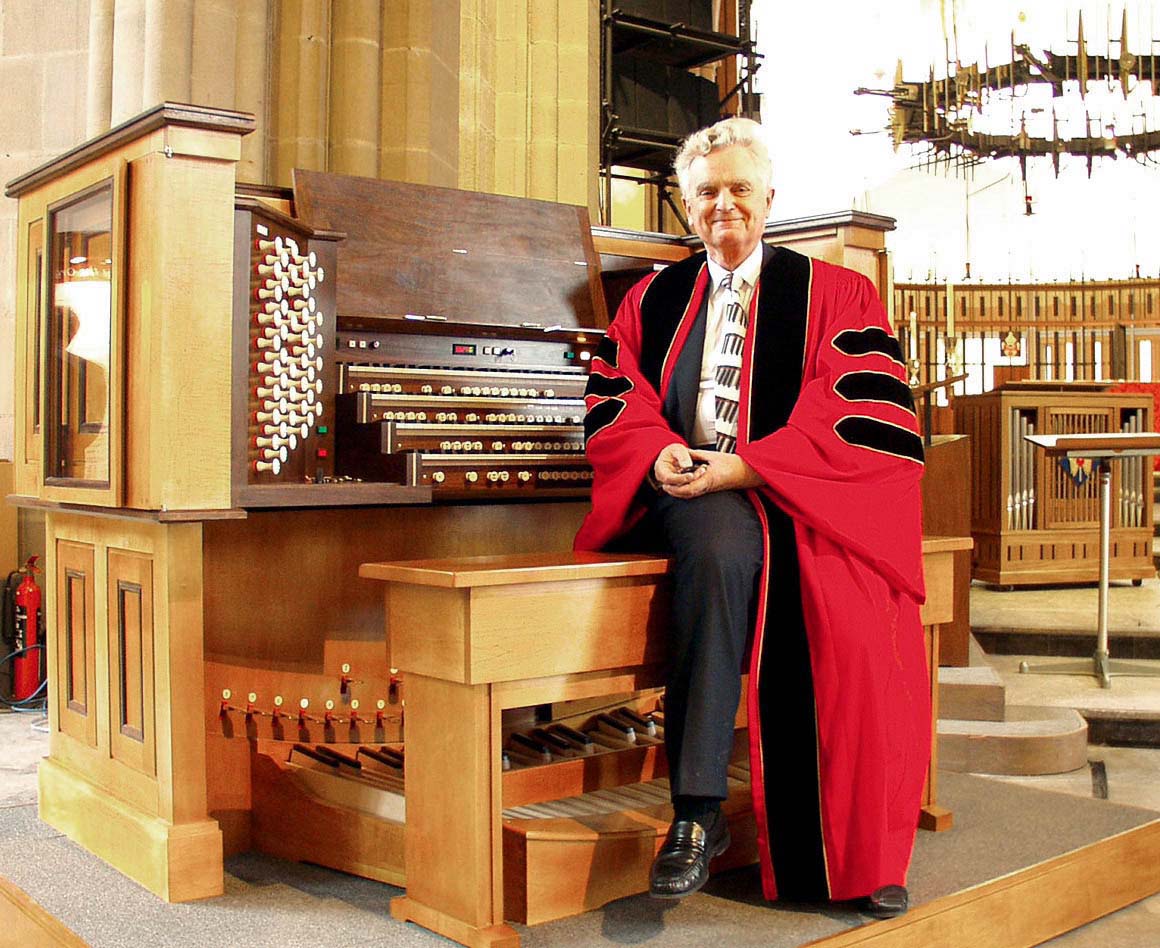

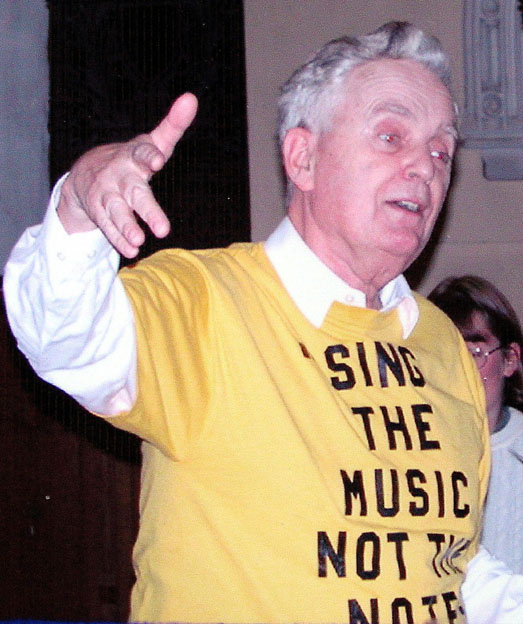

Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

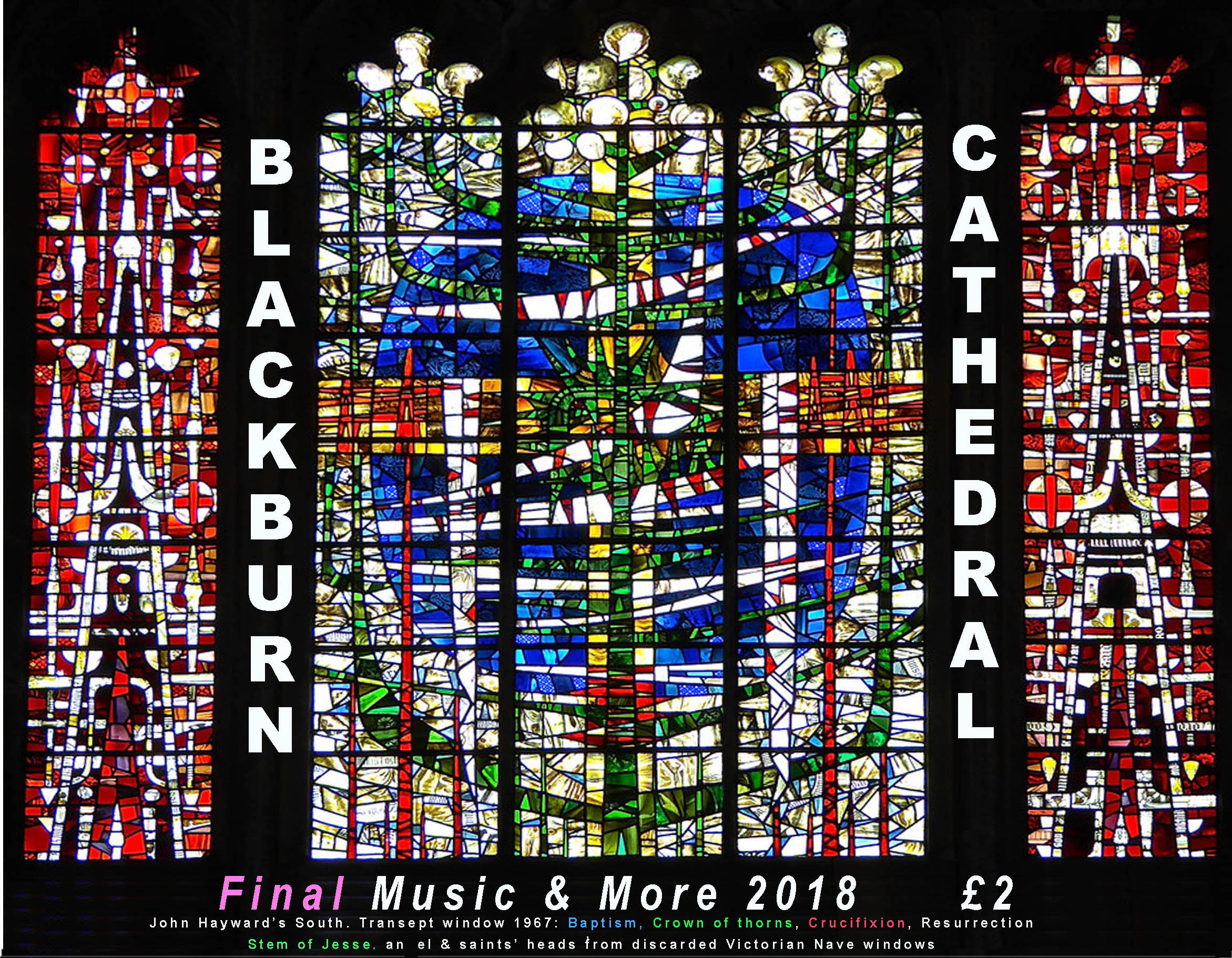

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

CONDUCTING

Eye contact (i)

I recently attended a concert given by a choral society which was accompanied by a fine organist. Their conductor is a well-known musician. But I was horrified to see that he spent 95% of his time, when conducting, looking at his score rather than looking at his choir.

Why was I horrified? Because, by looking at his own music, he was conducting himself not his singers. Consequently, although the choir sang the notes more or less correctly, there was no inspiration – no feeling of, ‘This is special, this is great music, these are timeless words which should give a message of hope to the world’. Such inspiration should have been given continually by their conductor through eye contact – but he didn’t, because he was looking at his music, not at his musicians. He just beat time, and even that wasn’t really necessary, for the singers knew the notes and, in any case, they weren’t following him, they were following the organist.

Oh, oh, oh, OH! why do so many illustrious Directors of Music conduct their choirs for hymns? If their choirs can’t sing hymns together they have no right to be singing in those stalls. And, in any case, the choirs are following their organists not the conductors. But most conductors don’t realize this!

Eye contact in so much of life is essential if we are to make creative communication with the people with whom we have to do. Whether it is in conversation, or shaking hands or leading a rehearsal or conducting a concert. Only when one is looking at a person, or a group, in the eye can one really get one’s message across.

To put it in negative terms, George Bernard Shaw wrote, in his preface to Pygmalion, ‘It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him.’ And that Englishman needn’t necessarily say anything. A look is sufficient. Many of us living in England may have experienced this; it’s called class distinction!

I once saw another director of music (who wasn’t usually renowned for looking at his singers) conduct an orchestral movement in a concert – but this time he looked at his instrumentalists the whole time! His eye contact conveyed the spirit of the music to every player. I was amazed. It was a superb performance.

Afterwards I congratulated him on looking at his players so creatively instead of looking at his music. But he said, ‘The sun was in my eyes, so I couldn’t see the score!’ He, alas, on that one and only occasion, had had discovered that he needn’t conduct ‘notes’ (as was his practice previously) but conduct the music, which means feeling expression and phrasing, and feeling the message and architecture of the music.

Alas, thereafter, he reverted to his previous custom of lowering his eyes (unconsciously) to his score once every five seconds, to reassure himself that he knew what he was doing. If a conductor needs reassurance, he’s not in the position to give confident command. But with eye contact he could so easily have raised the standard of his performance by more than several notches.

Do choral conductors realize that they are not conducting notes? e.g. ‘I’m conducting the chord of G major and then C major.’ The actual pitch of the notes has nothing to do with his conducting. But what he should be conducting is the spirit of the notes and the spirit of the words. His job is to inspire, not necessarily to beat four beats in a bar; the singers know that the music is in 4/4. What they need is something more than that. They need to be enthused – to communicate to their audience that this music and this text are special, be it ‘just’ a verse of a hymn or the entire B Minor Mass.

And this, I suggest, can only be achieved when the conductor looks at his singers 95% of the time. Whenever he drops his eyes to look at his score, even for a moment, the message his singers receive is, ‘I’m not sure what comes next, so just carry on singing until I’ve checked it out!’

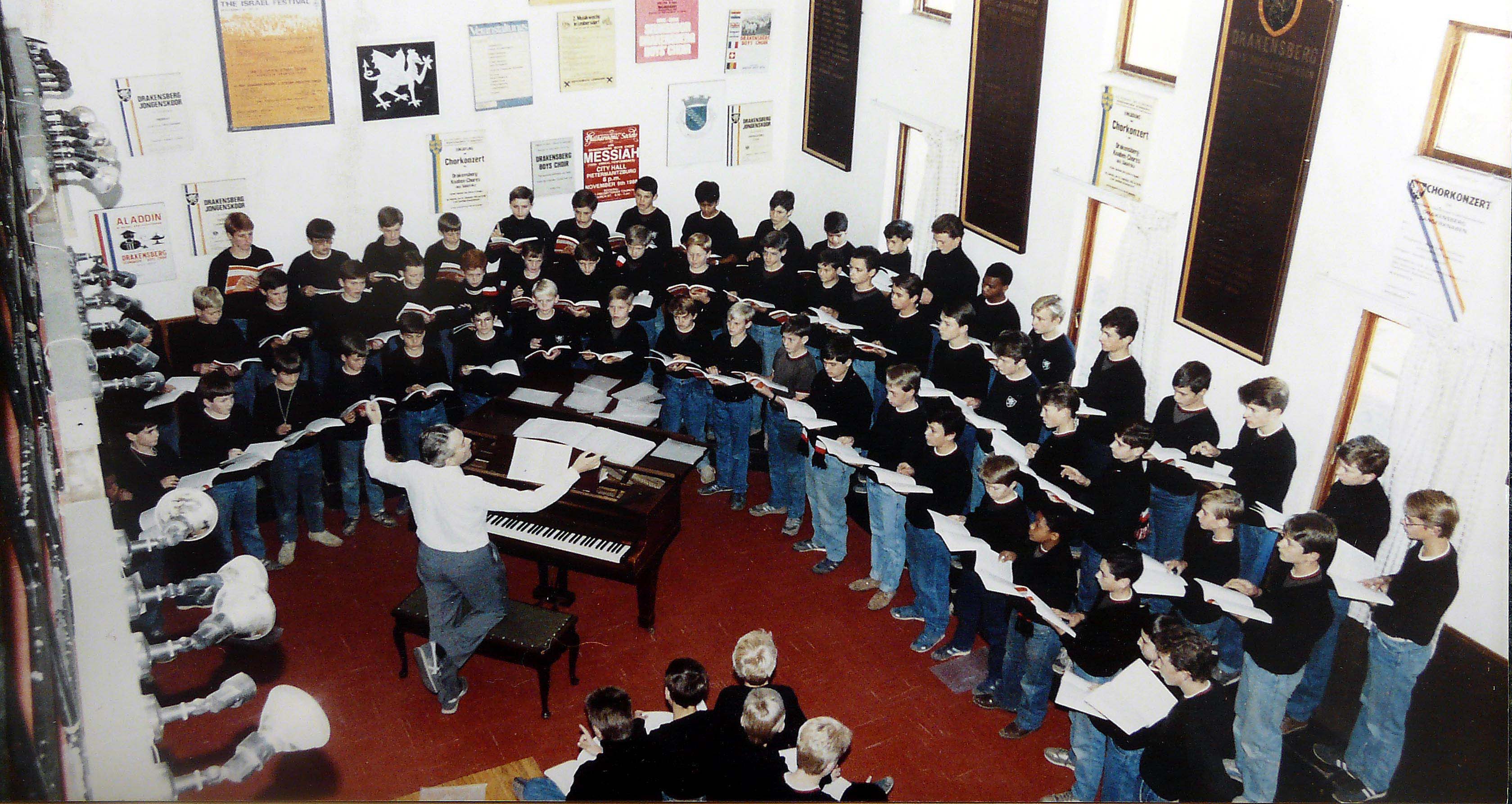

JB conducting the Drakensberg Boychoir, South Africa, with every singer looking at him, because he is looking at them.

The conductor should be the physical embodiment of the music he is conducting just as fully as an actor inhabits and creates the character he is playing. The conductor takes upon himself the embodiment of the music so that he may inspire his singers to project this spirit into their singing.

The choir are there to tell a story, be it, ‘There is a green hill far away’ or ‘Credo in Unum Deum’. The singers must see the hill (and it must be green, not blue!) and they must fully believe in One God – for if they don’t, their uncommitted singing will show their unbelief. (If they are non-believers, they must act as though they are believers for this performance, just as ‘well behaved’ actors can play the part of a murderer convincingly. It is the conductor who must enable his singers to convey this message, both in meticulous rehearsals and in creative performances.)

Eye contact (ii)

What should a conductor do when the organist is playing an introduction to an anthem, be it a long introduction (Zadok the priest) or a short one (Stanford in B flat Magnificat)?

Most conductors I’ve watched look at their score until a bar or so before the choir should begin. They don’t prepare their singers in any way, for they give the impression (by not looking at them) that the introduction has nothing to do with what the singers are about to sing. Rubbish! The introduction has everything to do with what the choir is about to sing. Therefore the conductor should ‘embrace’ them into the playing of the introduction. ‘This introduction is for You!’ And it’s creative eye contact with the singers (as well as with the orchestra players) which does it.

What is ‘creative eye contact’?

It’s, “I’m feeling the beauty/glory of this music so strongly that you can feel it building up bar by bar, so that when you start singing, everyone will realize that this introduction has affected you to sing the very spirit of the words. And I’m looking at you all knowing that you can feel it too!"

What’s the point of an introduction? To introduce the spirit of the music which the choir is about to perform! The word ‘introduction’ comes from the Latin, ‘to lead in’. Therefore the introduction should affect the singers so directly that they will be inspired to sing fully in the spirit set by the introduction.

And the whole point of having a conductor is to have someone upon whom the choir, and orchestra or organist, can concentrate before the performance begins, to set the mood for that performance. If it’s exciting music, such as I was glad, or Zadok, then the conductor needs to enthuse his performers with excitement before they begin to sing. If, on the other hand, it’s a calm piece, such as Fauré’s Requiem, or even Jesu Joy, the spirit of that music and the meaning of those words, need to be communicated to the performers in such a way that they will feel the spirit of the music and words well before they take their first breath.

How often have I seen conductors looking at their score and not at their singers when their choir is about to sing Parry’s I was glad. That one-page introduction is thrilling in itself, but the whole point of it is that its excitement grows and grows so that the choir should be fully prepared to burst in with, ‘I WAS GLAD!’ Therefore what should the conductor do when the accompaniment is played by an organist? He should, before the organist begins, look at his choir – every singer – with an all-encompassing glance, which gives the message, ‘Is everyone ready to sing this thrilling anthem? Let’s do it, then!’

Then he can glance at his organist (who knows how to play the introduction) with the same message of thrill, and then, during the build up of excitement, convey his own rising anticipation to his singers, by looking at them all throughout that introduction, to communicate his own thrill so that they do burst in, exactly on time, with the opening words.

And one more thing: notice that Parry repeats the word ‘glad’. He did this on purpose, of course! So the choir needs to sing the second ‘glad’ with even more excitement than the first. ‘I was glad, GLAD when they said unto me…’. A crescendo on the first glad will add even more thrill to the phrase.

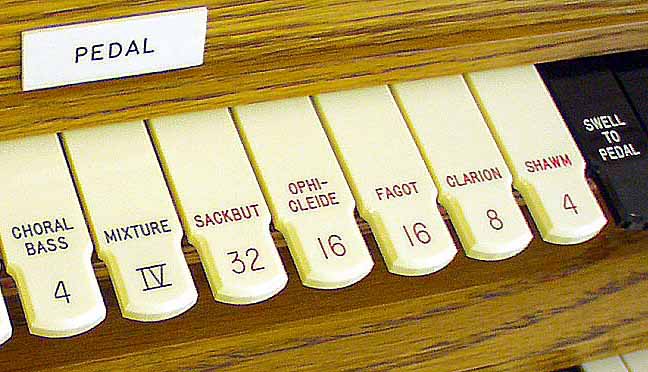

![]()

For short introductions, such as the Stanford in Bb Magnificat which has only two quick chords, the conductor needs to look at his choir intently in the spirit of those opening words and music – to feel an ‘empty’ bar so strongly this his singers can feel that the music is actually beginning before they start to sing. It’s like bringing soldiers to ‘attention’ – singers need to be poised and concentrated and be at unanimous attention before they start to sing, so that their initial notes are not only together and in pitch, but so that they have the essential sense of forward movement, which gives life to any performance.

By the way, the organist needs to play the first of those two introductory chords of the Stanford Bb Magnificat with a slight emphasis, not a light staccato, so that the singers are given a secure sense of key for their entry.

When an accompaniment is played by an orchestra, the conductor needs to give his initial attention to his players of course, but nevertheless his preliminary all-embracing glance should include his singers as well as his orchestra.

But is he aware that his players don’t need him to direct every note they play once they’ve begun? They don’t need his help in how to play their violins or trumpets. They need his inspiration to play the spirit of the notes, and his choir needs to feel that the introduction is leading them to sing their entry with enthusiasm and accuracy, so he needs to look at his singers increasingly as their entry draws ever nearer.

But, you may say, ‘I’ve seen orchestral conductors look at their scores frequently, but that doesn’t seem to affect the players.’

It’s more important to look at singers than it is to look at instrumentalists, for the singer’s whole person is the instrument, whereas an instrumentalist is usually of a professional standard and knows how the music should be played.

On the other hand there seem to be an increasing number of orchestral conductors who do conduct entirely from memory – Gustavo Dudamel is one example, and look how he inspires his players! Daniel Barenboim always conducts from memory; he doesn’t conduct notes, he conducts the spirit of the music – through his whole body and by his gestures and especially through his continual eye contact with his players.

And the reason that these great conductors don’t necessarily have to beat time is because all their players are listening to one another. There’s a corporate sense of rhythm which every player can feel however far they are placed in the orchestra from one another.

So I ask the question: do the singers in your choir listen to each other? For if they do, not only will their tone tend to blend, but there will be such a corporate sense of rhythm that you, their conductor, won’t need to conduct time, but ‘just’ to inspire them to sing the spirit of the words and the spirit the notes.

I once said to my Princeton Singers, in the USA, who were trying to get the rhythm absolutely correct for the opening bars of Howells’ Take him, earth, for cherishing, ‘Sing the music, not the notes!’ and their singing immediately was transformed, and they found that the music virtually sang itself!

But you may say again, ‘I always look at my singers when I conduct them!’ Do you? Are you sure?

For many years, at the start of my career, I thought that I was looking at my singers, but I wasn’t. At one of the rehearsals with my Northampton Bach Choir (when I was Director of Music of St. Matthew’s Church), I said, ‘Look at me!’ And one of the tenors said, ‘We’ll look at you if you’ll look at us!’ Whoops!

I confess that it took me several years before I knew that I really was looking at my singers rather than at my score.

The only way to discover for yourself if you are numbered with the sheep or the goats, is to conduct your choir with your copy closed. Try it!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013