How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

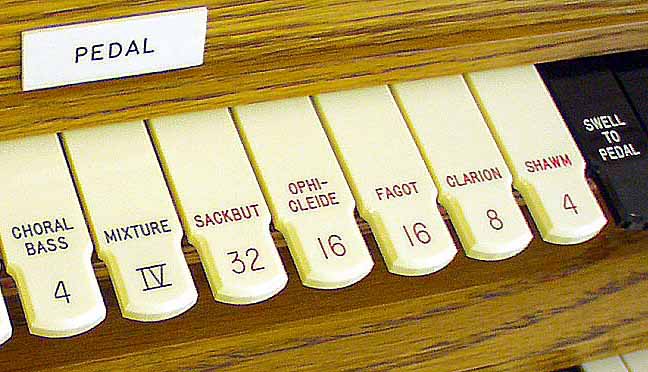

30 Major Musical Influences in my life. No. 3 of 3

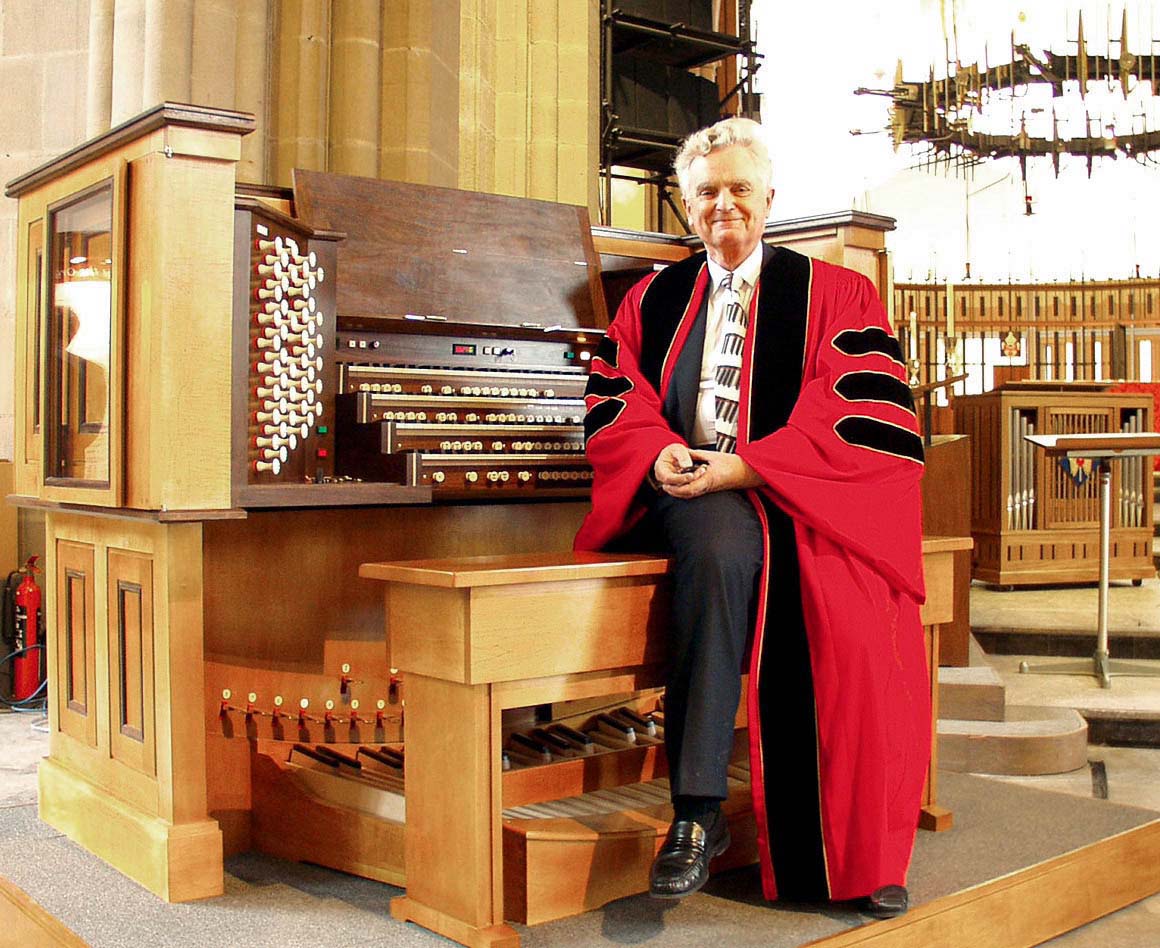

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St Matthew's Church, Northampton

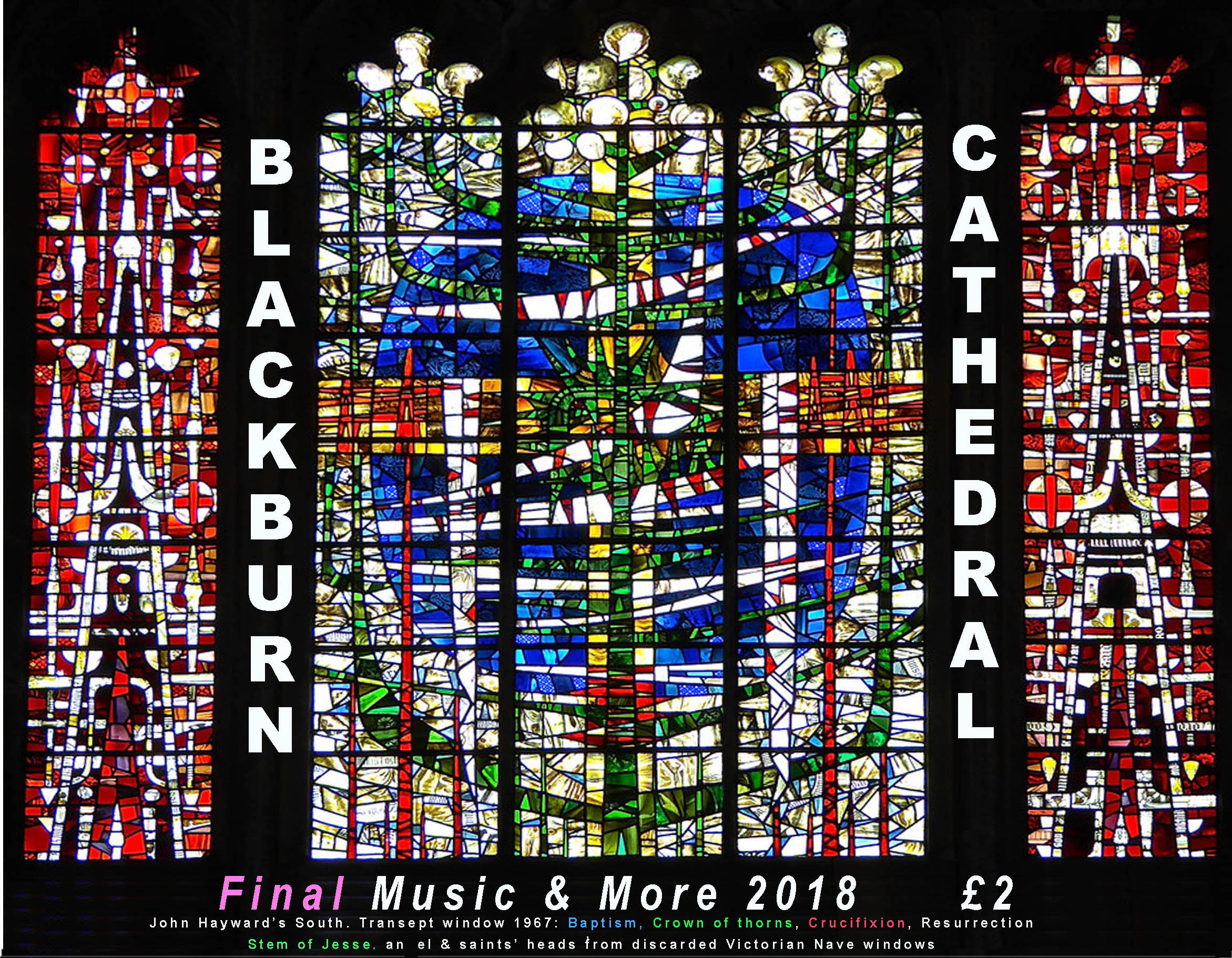

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

I share final memories of yet more musicians who have influenced my life profoundly. May they also influence yours.

Sir David Willcocks

‘DVW’ has been an inspiration to musicians throughout the world. He was a chorister at Westminster Abbey, was organ scholar of King’s College, Cambridge, was commissioned in the army in WWII and decorated for bravery. After the war he became organist successively of Salisbury and Worcester Cathedrals before returning to King’s as Director of Music, where he succeeded his former mentor, Dr. Boris Ord. After that he became Director of the Royal College of Music in London, and has, throughout his life and for many years into his retirement, led workshops and conducted concerts all over the world. His gifts and energy are amazing. I have learnt so much from him.

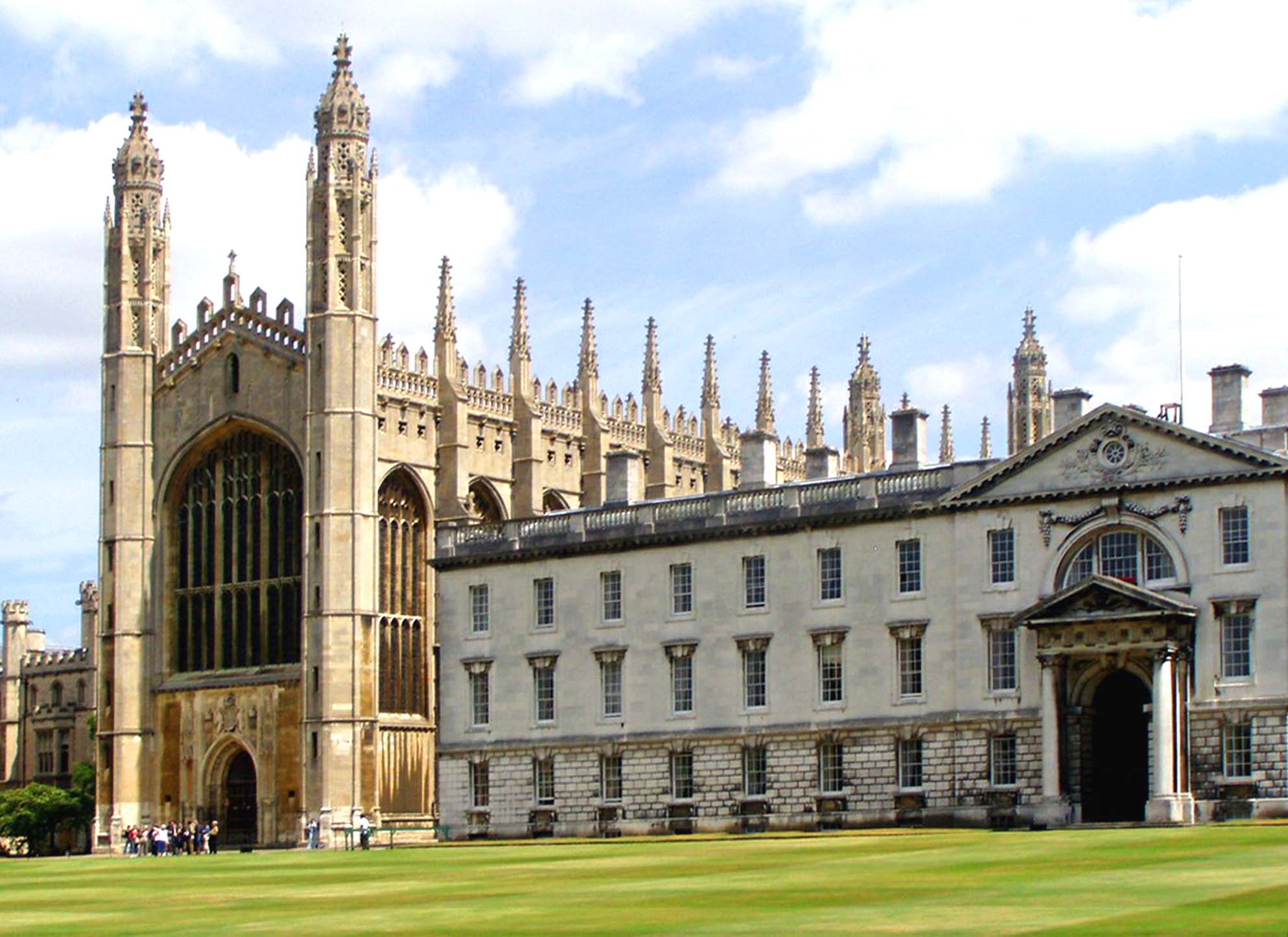

1 When he was Director of Music at King’s I wrote to him (for I had known him for a number of years) to ask if I may attend one of his choir practices in King’s Chapel. He replied, ‘Yes, be outside the chapel at 3.15.’

I arrived early and saw the choir being admitted to the chapel by the sexton, and then the gates were locked. At 3.25 DVW came along the path in suit and gown, holding some music and looking every inch like a headmaster. When he reached me I expected him to say, ‘How nice to see you, John; come along in.’ But he didn’t.

He looked at me for three long seconds and said, ‘I don’t usually do this …’ (There’s no answer to that – I had to wait for the second part of his sentence.) ‘… so please sit as far from the choir as you can and don’t make a sound!’ I meekly followed him into the chapel and did as I was told. (I told this story, with Sir David’s permission, in my book, How to be a successful choir director.)

That traumatic experience taught me one of the most important lessons I have ever learned, for DVW conducted two choir practices at King’s every day; his choir sang daily services during term, and they made recordings, gave broadcasts and went on foreign tours. But, although this rehearsal was just for today’s Evensong, it was so special to DVW that nothing would stand in his way to give of his best to his choir. And so I ask myself the question, ‘Is my next practice as important to me as that?’ For if it isn’t, it won’t be important to my choir, and their singing will be sub standard. How important is your next practice to you?

I learnt two more lessons that day.

2 For most of DVW’s rehearsal that afternoon the choir sang unaccompanied.t You may say, ‘That’s all very well for King’s choir, but not for mine’. Yes it is!

If my village church choir can rehearse hymns unaccompanied (I only give them the first chord and then tell them to get on with it, whilst they watch their leaders on either side to ensure that they come in together), you can do it with your choir. (By the way, I interrupt my choir frequently to ask, ‘Was that a good start? Try it again. Are you singing four beats per bar or only two. Which is better?’ (Two.)

Your job as choirmaster is to make yourself dispensable by turning your choir into leaders, not followers.

That is why my choir sings warm-ups and rehearses hymns unaccompanied – to build up their self-confidence. And they respond marvellously.

But I’ve seen cathedral directors of music playing the piano when their choirs sing warm-ups, hymns and psalms. Why?

Answer: because they enjoy playing the piano with their choirs. But that’s not what they’re there for. They’re there to train their choirs to lead; but how can they learn to lead when you are leading them on the piano?

3 At that ever-to-be-remembered rehearsal DVW was insistent that every fault was corrected immediately. He never said, as so many of us do, ‘Well, I’m sure you’ll get that right on Sunday!’ And he only corrected one error at a time. He didn’t give a list of faults, as many choirmasters do: ‘At the top of page 3 we need to sing more firmly, and at the bottom of that page hold that last note for its full length, and be careful about the tuning in the middle of page 4.’ I’ve watched choristers’ faces when their choirmasters give such instructions, and they immediately ‘turn off’. Their choirmasters may be fully committed to what they are saying, but they’re not aware that their choristers aren’t listening.

Did you notice that the instructions given above were unclear? What does firm singing mean? It needs to be rehearsed. How many beats are there on that last note of page 3, and is the choir singing flat or sharp in the middle of page 4 – and which voice-part is at fault? When faults are to be corrected, be specific about defining the error, and don’t go on to the next point until that first point is wholly right. If that’s good enough for Sir David, it’s good enough for us.

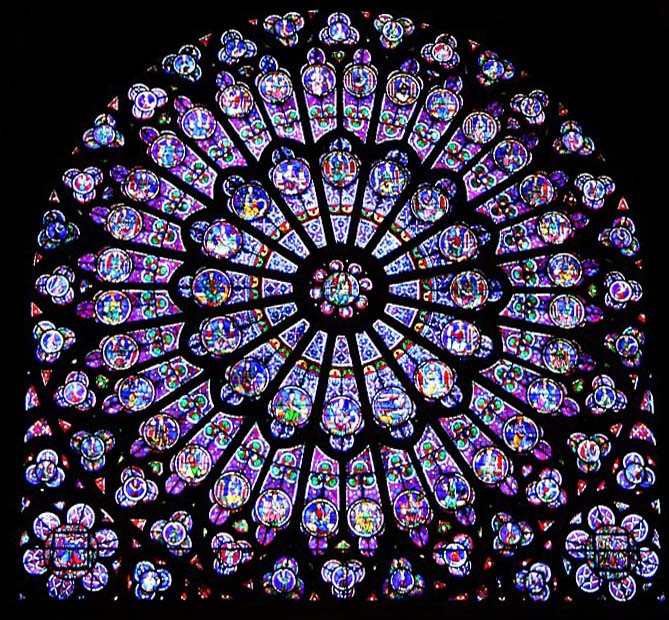

4 In 1981 I was invited to conduct the USA’s Annual RSCM two-week course in the enormous Princeton University Chapel (this was a year before I was appointed to Trinity Church in that University town).

Before my course began DVW led a week’s workshop at Westminster Choir College just down the road, and so I went along to one of his sessions to get a musical boost. I found him conducting about 150 singers who were seated in an arc around him, seven rows deep. I sat in the back row, got out my pencil and pad and began to take notes. Suddenly DVW stopped the choir, walked through several rows of singers and addressed the men sitting on the back two rows. I immediately sat up straight, for I realised that I was vulnerable. i.e. I tried harder because the conductor had demonstrated that he could stand directly in front of any one of us!

That was a particularly helpful lesson for me that week, for I had 200 singers on my course from all over the USA, and full rehearsals were in the enormous University Chapel. The furthest singers were 20 yards from me, and so at every practice, whilst they were singing, I went round to every row to look each singer in the face. That immediately gave them the feeling that I cared how they were doing, and so they all tried harder.

I’ve done that with my other choirs ever since – and it immediately pays dividends, for each singer thinks, ‘He knows that I’m here, and he cares how well I’m doing.’ That is a very positive message to give to your choir at every rehearsal – but it takes courage to do. Try it!

5 And there’s one other thing about conducting which I’ve noticed amongst some of my senior brethren. They are so intent on performing their anthems in strict time that, frequently, their choirs have to snatch a breath in order to sing the next phrase, and this always leads to an unwanted sharp emphasis to the last note of the previous phrase.

This occurs in some hymns, too. For example, in the middle of each verse of ‘Tell out my soul’, when sung to Woodlands, if the pulse is to be kept strict at ‘… give my spirit voice,’ then singers must cut the note short on ‘voice’ and therefore inadvertently emphasize it in order to snatch a breath for the next phrase. This is unmusical. It’s the easiest thing in the world to ‘relax’ the tempo at that point – not adding an extra beat, but just finishing the previous phrase musically, and then taking a quick breath. It can be done if the choirmasters know in their own minds exactly what is required, and then rehearse their choirs in this, and play the organ in a similar manner for the service. I did this last week for my village church choir, and they got the message immediately. So did the congregation. If they can do it, so can your choir.

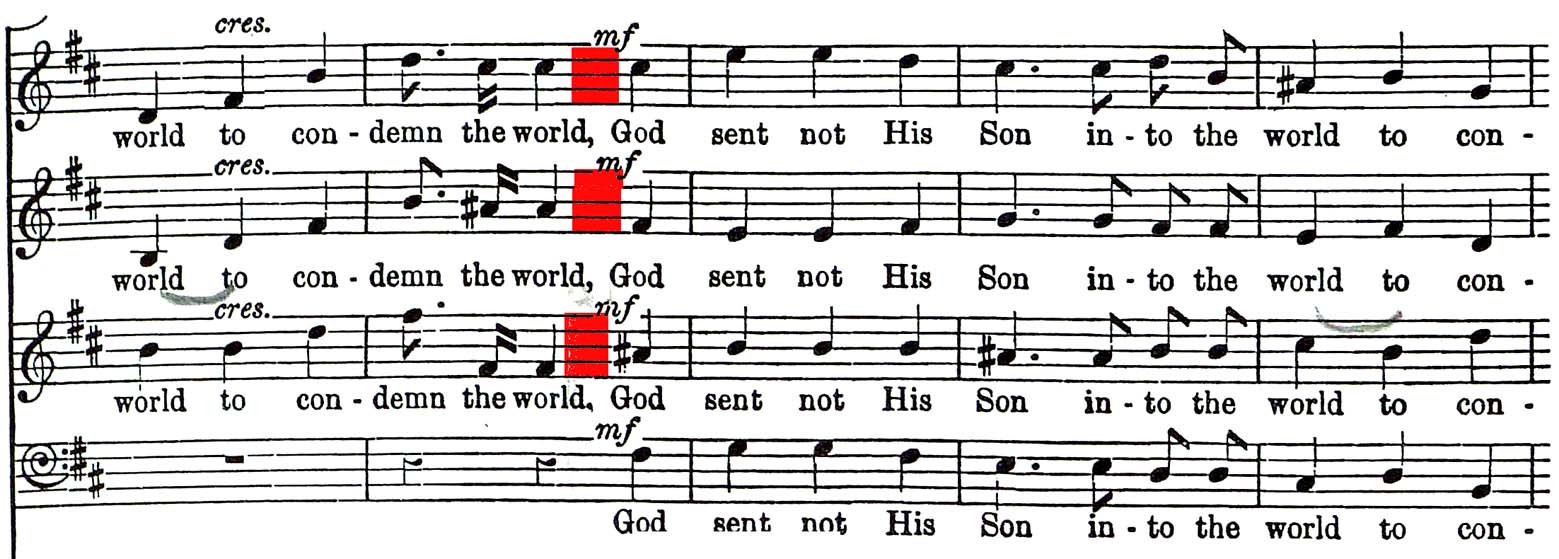

This is a simple example. But there are very many other examples in well-known anthems, such as in the ubiquitous ‘God so loved the world’. Page 2, ‘… to condemn the world, God sent…’ There’s no rest after ‘world’ but a breath has to be taken, therefore relax the tempo at that point, sing ‘world’ musically, take a breath, and then continue. When you’re conducting this, don’t indicate where the breath should be taken, for this will again lead to a moment of stress, but just lift your hands with a loose wrist on ‘world’ and breathe with your choir, showing that the tempo is relaxed, and then lower your hands to bring the choir in on the next word. When you’re going to relax the tempo, the conductor must also be relaxed.

And, of course, when you’re conducting DVW’s lovely arrangement of ‘Away in a manger’ you have to relax the tempo at the end of the third line on the word ‘lay’ (‘… looked down where he lay, the little Lord Jesus…’) for there are continuous quavers in the lower two parts which must never be ‘snatched’. So a tiny break for a breath is called for, relaxing the tempo at that point.

And this leads me to another mistaken technique I’ve noticed in a few experienced choral conductors. Some of them don’t really believe that their choir will come in on their first note, and so they tend to give a ‘sledge-hammer’ beat to make sure that they do. If I were to mention this to a senior colleague after I saw him conduct his fine choir in this manner only fairly recently, he might say to me, ‘If I don’t conduct the first note really firmly, they won’t come in.’ He’s quite right, they won’t. And do you know why? It’s because he’s trained them not to come in unless he does conduct that first note with undue emphasis.

He might ask me, ‘What should I do, then?’

Answer: Rehearse them to come in with a gentle beat. Give them a clear indication that they should breathe exactly one beat before they start singing (the conductor must breathe this breath with them) and they will start musically. Singers need to be told that it is their responsibility to ‘come in’ at the beginning of phrases. They need to be rehearsed in taking that responsibility, for it is they who need to make the effort, not you, to begin every new entry on time.

Dr. Barry Rose

Barry with JB at Richard Tanner's 40th birthday party

Barry has been one of this country’s most influential choirmasters not only through his years at Guildford and St. Paul’s Cathedrals and St. Alban’s Abbey, but also through the many choristers and organ scholars who have been through his musical hands, some of whom hold illustrious cathedral positions now, where they are continuing his great work.

I have learnt three important techniques from Barry:

1 It’s sometimes helpful to ask your choristers to sing a short passage incorrectly on purpose. For example, almost every singer takes a breath halfway through lines of words when singing hymns. (‘When other helpers – breath – fail and comforts flee…’) This is unmusical and sometimes makes nonsense of the words, (‘We plough the fields and scatter’ – breath) but it is difficult to eradicate. Therefore, at your next practice, ask your singers to sing a short passage incorrectly on purpose: to take a deliberate breath halfway through every line of the first verse of a hymn: ‘Saviour, again – breath – to thy dear name we raise – breath – with one accord – breath – our parting song of praise…’. That way they will realize how unmusical it is and how it ruins the meaning of the words. So after they’ve had a good laugh, they’ll be ready to rehearse it as you want it to be sung.

The trouble is that most of us go on auto-pilot when singing hymns during services, for we sing without thinking. This is a bad habit which needs to be brought to your choir’s attention again and again.

2 Barry is very keen that choirs should sing in colour. This can be introduced by asking your choir to sing an incorrect word or two. ‘There is a blue hill far away within a city wall…’ You will find that they automatically stress the new words. Then ask them to sing the right words, and the hill will immediately become really green and be surely placed outside the city wall. Other examples spring to mind: ‘Half my hope on God is founded…’ ‘Lazy shepherd of thy sheep…’ ‘In the hot mid-summer, frosty wind made moan…’. By doing this occasionally your singers will immediately impute fresh colour and meaning to the correct words, and this is a prime reason why they are rehearsing hymns and anthems – not just to get the notes right but to realize, in the fullest sense of that word, the message they are singing.

3 And Barry insists on ‘live’ consonants. Consonants are the letters that so many choirs tend to miss. ‘Love is kine Ann suffers long…’ The letters ‘D’ and ‘T’ are frequently missing not only, alas, in our everyday speech but also in our singing. Consonants must be sung deliberately; singers have to make a conscious effort to sing them. Spoken English is sadly deteriorating. (Many folk these days can’t even say the word ‘deteriorating’!) The day after Mundy is now Choosdi, and often one cannot understand a word that actors say, for they mumble. What can choirmasters do to correct such lazy diction?

Barry insists that some consonants should be doubled, (a) to make the text clearly understood and, (b) to impute colour to the words – such a Llove, prraise, ffairest, mmy, and so on. Also he insists that in order to get a unanimous attack at the beginning of a work, the initial consonant needs to be sung before the beat, so that the vowel comes on the beat. ‘Prrr/aise, my soul…’, ‘Mmm/y soul doth mmagnify the Llord…’. When you listen to recordings of Barry’s choirs, these wonderfully creative techniques will immediately strike you: the placing of initial consonants, the meaning of the words and the many colours he creates. Alas, so many of us are satisfied with monochrome performances.

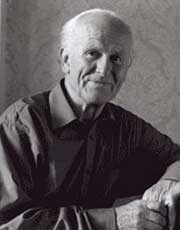

Dr. Freeman Dyson

Dr. Dyson was one of my choir parents when I took up my position as Director of Music of Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ: his daughter was head chorister of my girls’ choir. He is regarded as one of the world’s most gifted theoretical physicists.

He started young: when he was five he worked out how many atoms there were in the sun! (His father, Sir George Dyson, was Director of the Royal College of Music when I was major organ scholar there.) I once asked Dr. Dyson to define the second law of thermodynamics for me. He gave me a two-word answer: ‘Entropy increases.’ That means that there’s always a natural increase in disorder. It takes more energy to put things right than it did for them to go wrong.

Its application to choir training is very practical: a choir’s standards will inevitably deteriorate unless you do something about it. Or, putting it another way, choir training is like pushing a man up a greasy pole; once you’ve pushed him up, he will begin to slide down, and so you’ll need to push him up again. Therefore you, the choirmaster, must continually polish the things that your choir got right last week for, unless you do, they will begin to deteriorate.

In practice that means, never just sing through an anthem. Instead always find at least one thing that needs polishing, even if it’s only one note. If you’ve reached ‘perfection’ in your rehearsal (which no-one ever does) it means that by the time Sunday comes round entropy will have done its work and the performance will be less than perfect.

And we must begin with ourselves. We have to push ourselves up that greasy pole again and again, for entropy affects us, too. Our choirtraining skills need constant fresh inspiration; that why it has been such an honour to write these articles for OR – for in them I have challenged myself as well as you!

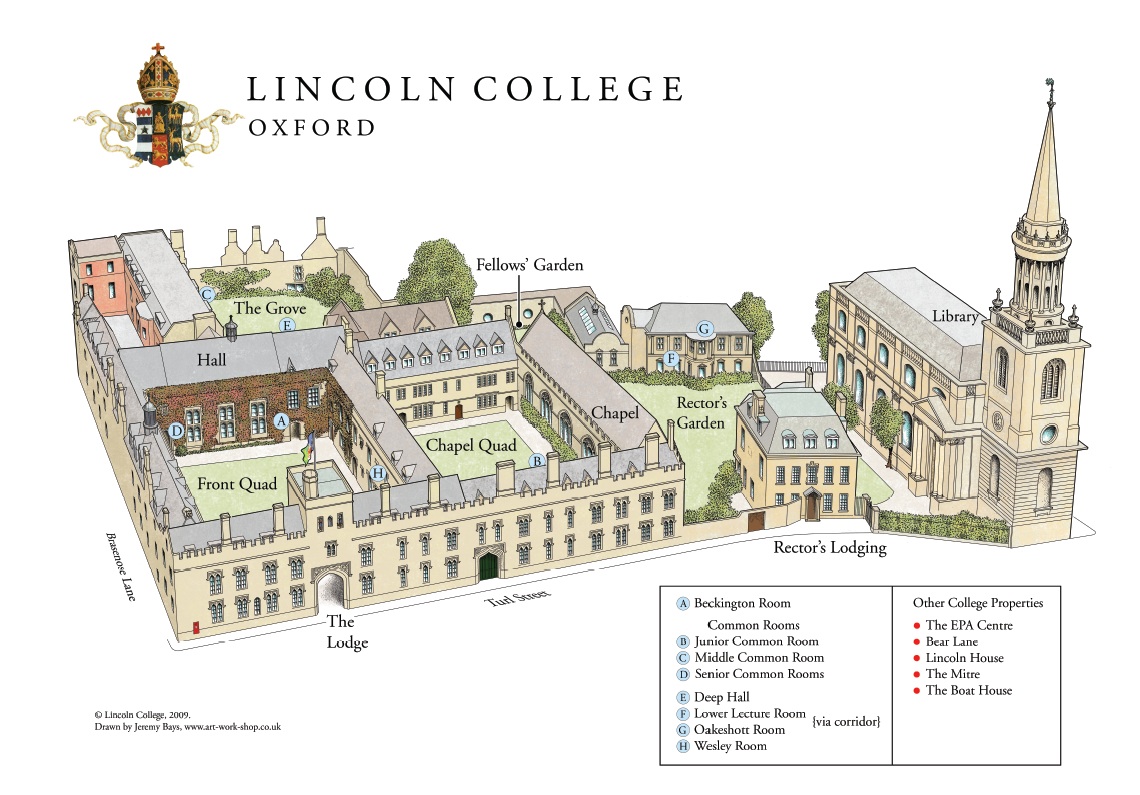

Oxbridge

After my studies at the RCM it was my privilege to win organ scholarships both to Oxford and Cambridge. And it was whilst at these universities that I met fellow students for whom Christianity was a living, joyful and ever-present way of life. It is through these Christians, and many others, that my own life has been continually challenged, and this is particularly true for me as a choirmaster. For my task, like yours, is to recreate some of the very finest music ever composed which is set to words which proclaim timeless truths.

It is our vocation to lead the music for worship – and to care deeply not only for the music, but also for the words to which the music is set. It is our vocation to lead the congregation not only in the singing of hymns, but also in the understanding of the words that they sing. In other words we need to jog them out of the autopilot mind-set to which we are all too easily prone.

And this need to interpret the words comes primarily from our own Christian commitment.

The Choristers’ Prayer says it so well: ‘Grant…that what we sing with our lips we may believe in our hearts…’. So we choirmasters need to believe in our hearts first so that our choirs may sing with their lips and from their hearts.

What you believe will show automatically by the way that you lead your rehearsals.

South Africa

A few years ago, when I was leading workshops and lecturing in South Africa, I was asked if I would listen to a school choir of deprived black children. ‘Yes, of course.’

When I entered the hall I found the children, who were between the ages of 12 and 18, standing immaculately in three rows on risers, dressed in smart school uniforms. And they sang to me for an unforgettable hour. And how they sang! The music was unaccompanied and in glorious harmony. They sang with fervour, with faultless intonation and total commitment as they watched their conductor like hawks. I was swept away by their singing, for I had never heard anything like it.

In fact I was lost for words as I tried to thank them afterwards, and burst into tears as I shook their hands before they left.

But what has remained with me from that amazing hour was not only the perfection of their singing, not only their sense of self-discipline, or even their pride in their astonishing musical achievements, but because everything they sang (and they sang in languages that I didn’t understand) clearly proclaimed that they believed every word, for they were singing about themselves, about their trials and hardships, and about their unquenchable belief that they would somehow come through them all triumphantly.

That choir was, for me, the very finest choir I have ever heard, for they sang not only the notes and the words, but they also sang the spirit of those words from deep in their hearts.

And so I ask myself, ’Do the singers in my choir believe every word they sing?’ for that is the most precious blessing I can bestow upon them – the gift of understanding the Gospel, and taking it into their hearts. And if our choristers don’t yet believe, to whom can they turn for instruction and enlightenment and inspiration except to us, their choral directors?

‘Christ has no hands but your hands to do his work this day;

no other feet but your feet to guide folk on his way;

no other lips but your lips to tell them why he died;

no other love but your love to win them to his side.’*

* Reproduced, with permission, from John Bertalot’s book, How to be a successful choir director, published by Kevin Mayhew.

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 201