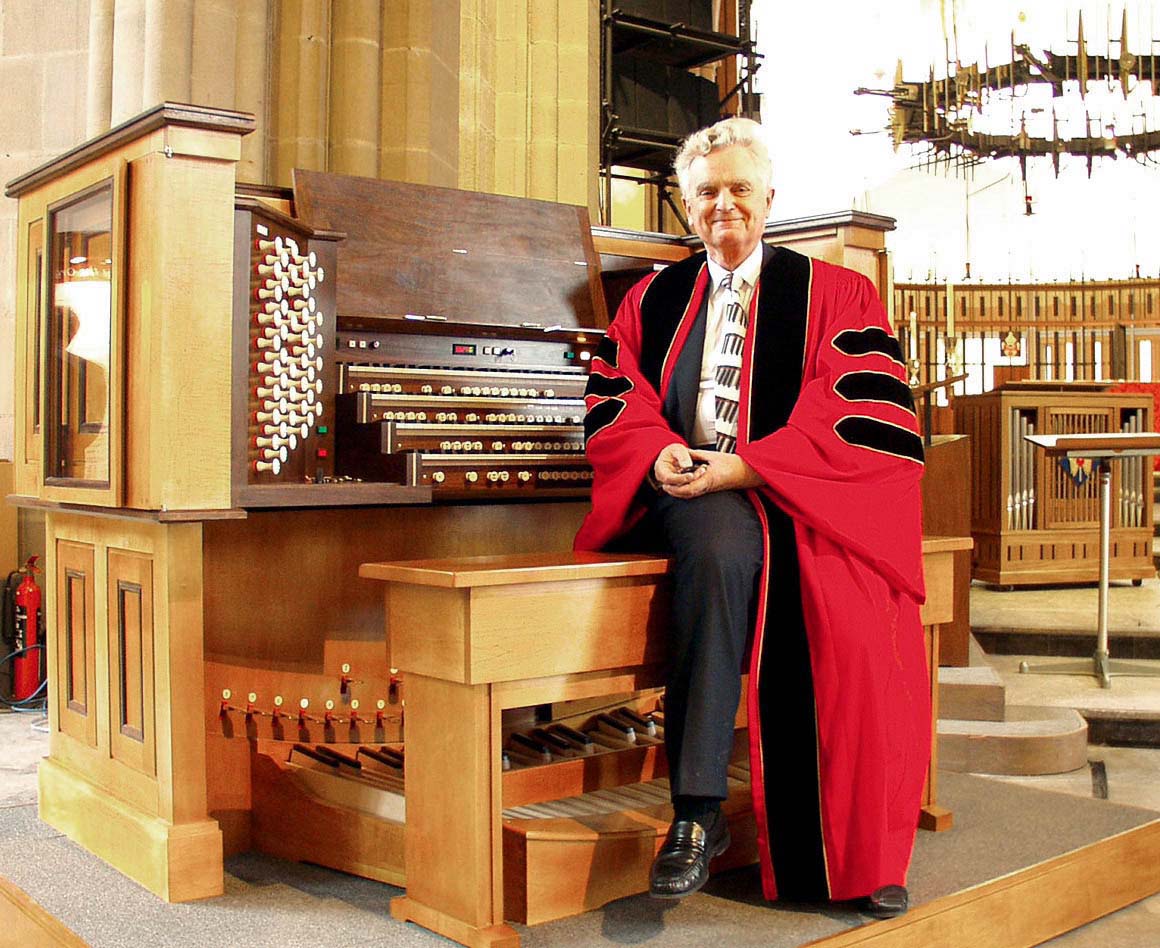

The Cathedral Organists' Association Conference at Exeter Cathedral, May 1st 2013

John Bertalot's hand-out to encourage a successful method of teaching children to sight-sing

after demonstrating his method of teaching sight-singing to the Conference (see article 33).

1 The choristers must do the thinking, not the choirmaster

The key to success in teaching anything is to enable the pupil to ‘own’ the right answer – by asking the right questions. Is it (a) or (b)? He/she will then take pride in ‘doing it right’ thereafter.

2 Rehearse mainly unaccompanied

We tend to say: ‘No, you’re singing a G instead of an A. This is what you should sing’ – and then we play it for them. So the chorister has no ownership of the right answer. He’s put in the position of ‘having to do as he’s told’ – for the teacher owns the answer not the chorister so there’s no sense of achievement for him in that. You’ve taken away his opportunity to succeed, for you’ve done the thinking for him.

3 It’s possible, with this method, wholly to dispense with note-learning

When cathedral probationers are taught to sight-sing (possibly after the model JB suggested),

after only ONE MONTH of instruction, they should be able to sight-sing a Palestrina Motet slowly & correctly (with only one or two stumbles which they should be able to correct for themselves).

JB was able to do this in Princeton when he rehearsed his probationers only twice a week. Everything (total concentration for 45 minutes, vocal production, breathing etc.) was geared to sight-singing. i.e. they had to do the thinking because I continually asked the right questions - about one every 15 seconds. AND IT WORKED!

4 We choirmasters may not be aware that our singers are following not thinking!

When only semi-taught probationers are admitted to the choir, they tend to follow, a fraction of a second later, what their senior peers are doing, so they’re not looking at the music. And the choirmaster isn’t aware of this! And their senior peers are singing, a fraction of a second later, what the piano is playing. And the choirmaster isn’t aware of this! They’re not sight-singing, so they’re not thinking, so why should they concentrate?

That’s why you have to give every instruction twice –

because only half your choir is really paying attention.

5 It’s essential that individual probationers are given the opportunity to ‘have a go’

Therefore probationers should be enabled to discover for themselves (by the Director asking the right questions) several new skills at every practice. Individual probationers should continually be given the opportunity to ‘have a go’ at getting a challenge right – perhaps two attempts – and then go on to the next probationer. Thus the spirit of competition enters into the practice – which is always a good thing.

a. Show me how you should stand when singing. Who’s got the most mobile mouth? Let’s all do it

b. Who can clap the rhythm of those two bars correctly? Nearly right; what was the problem?

c. Who can pitch the next note? Well done. Let’s all do it. Were we together – really together?

d. Which letter did you miss out in that phrase? Who can sing it correctly for us?

e. Who can sing that phrase in one breath? Now let’s all do it.

f. What have we learned today?

6 Training probationers is too important to be left to music assistants unless they know how!

For cathedral choristers their training in their first few months as probationers is key to their whole career in your choir. And everything that they are challenged to get right they must get right. Once ‘nearly right’ or ‘most of you are right’ is acceptable, that’s how it will remain: they’ll nearly concentrate, they’ll nearly try hard, it won’t matter if only most of us sing the right notes…

7 Continually encourage individual singers to ‘have a go’

Teaching basics is a highly skilled skill! Therefore the Director of Music (perhaps with the organ scholar watching) should lead the probationers’ practices to form their enthusiastic attitude of ‘Let me try – I think I can do it’ from their very first practice. This will be the attitude they will show for the whole of their choir career. So enable them at every rehearsal to volunteer to ‘have a go’ on their own.

8 No No!

By the way, the word ‘No’ is a put down; it does not encourage.

Whereas the word ‘Nearly’ means, ‘If you try again you’ll almost certainly succeed.

What was nearly right? OK – have a go at singing it completely right!’

9 A really creative way to begin every choristers’ practice!

At the choristers’ rehearsals let them try to sing the pitch of the first note of every psalm and anthem you are about to rehearse. That way they will be looking at the notes creatively and so they will continually be teaching themselves to sight-sing better and better.

JB found that, after instituting this with his Princeton choirs, the choristers, on their own, vied with each other to be the first to sing the first note of every anthem they were about to rehearse. They were right 9 times out of 10. In other words, they were ‘hooked’ on sight-singing, they were hooked on concentrating, they were hooked on trying hard, as a way of life in the choir!

10 We all play the piano far too much!

Why is the piano being played so much at rehearsals? Why play the hymn tune, why play the chant? By so doing the choirmaster is doing the leading, not the choristers. So for example, when rehearsing Stanford Magnificat in Bb, just play the first two chords and you’ll notice (and they’ll notice) that they don’t start together. (Very few choirs start really together!) So ask them what was wrong? ‘Can you do it better this time?’ By all means play the bass part – to give the harmonic sense – but never play ‘the tune’!

11 Give the note only ONCE!

‘Give the note or chord’ only once when rehearsing an unaccompanied anthem. This will take a lot of self- control on our part! (JB saw DVW rehearse a Byrd motet with King’s choir for 20 minutes, and the chord was given only once at the start! That was an inspiration.) Singers love to be challenged to find their own note when you say, ‘Go back to the bottom of page 2, bar 3….’ We all continually ‘give the note’ for we think that that saves time. But it dulls the singers’ concentration, for you’ve done the thinking for them.

12 It’s essential that choristers are given the chance to exercise their Sight-singing skills during choristers’ rehearsals – otherwise they’ll never improve.

When trebles find a passage difficult, ask individuals to volunteer to ‘have a go’ to show the rest of their peers how it should be sung. Give a chorister two attempts, then go on to another volunteer. Children thrive on a spirit of competition. It’s a sure way to create enthusiasm in your choristers – for that’s what you want.

These methods ensure that for full practices your trebles will have been thoroughly prepared and will be as professional as your lay clerks. (And, of course, asking questions is not appropriate during full practices.)

VERY YOUNG CHILDREN:

A choir-mistress in Rhode Island told JB that her newest choir children (aged 4 !) could read music better than they could read words. In other words, one can start teaching sight singing to very young children. She made large placards with notes written on each – and she held them up in rehearsals. ‘What’s this? A half note! Who can clap us a half note? Other placards had a treble clef, or a note G, or two or four notes – etc etc – so that she was constantly challenging the children to think.

Placards would be a way to work for the Music Outreach Programme… as long as the very end result was that the children would be invited to work out for themselves, section by section, the tune of a simple song.

NB: Always point to the notes so that the children’s attention may focus in the right place.

Please see ‘JB’s Choirtraining’ articles nos 15 & 16 for detailed 'how to' teach young children