35. Conducting an orchestra for the first time

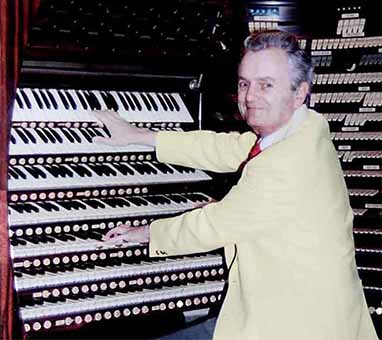

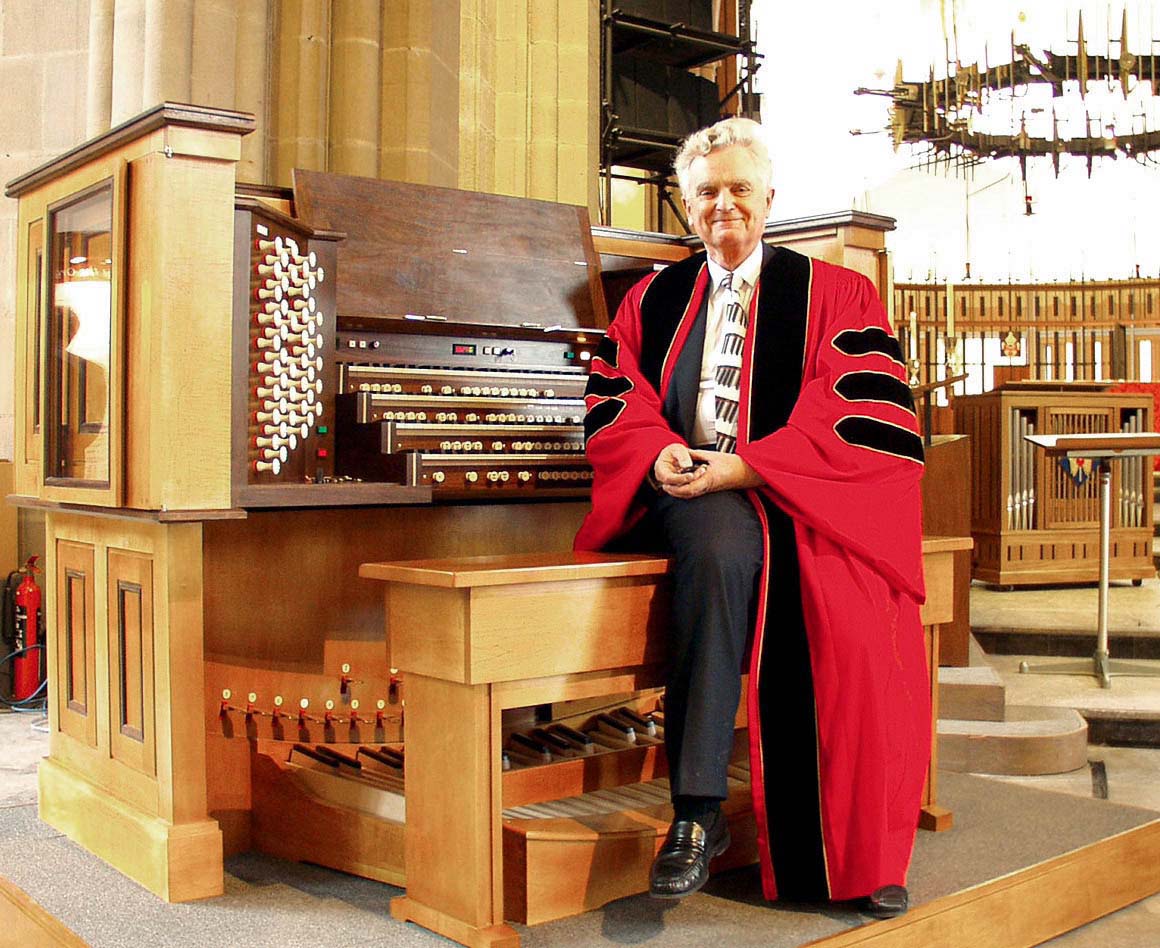

by Dr John Bertalot

Former Conductor of the Northampton Symphony Orchestra

Organist Emeritus, St. Matthew's Church, Northampton

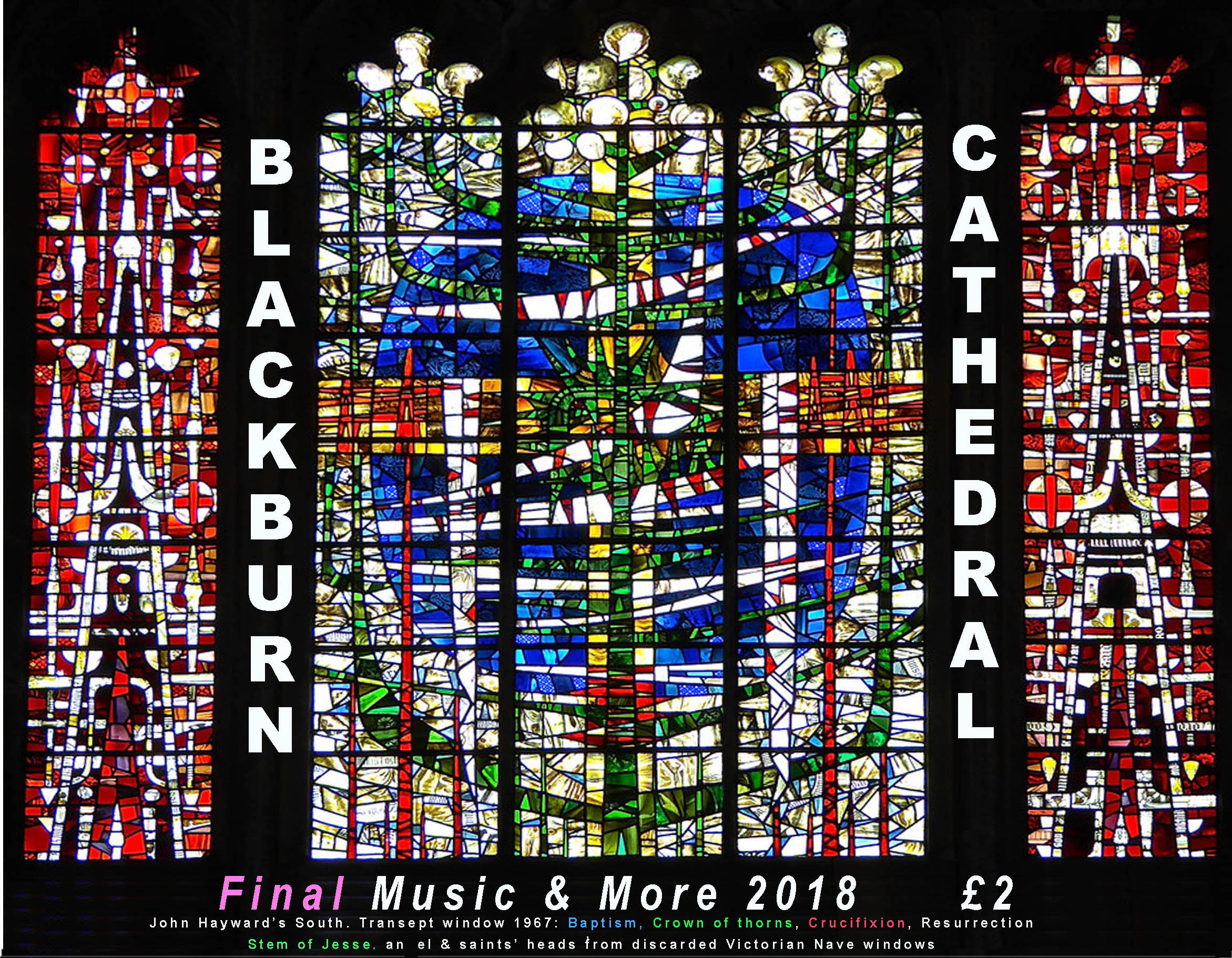

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ

Gustavo Dudamel

(He's the best - always conducting from memory and always inspiring his players by his facial gestures)

Having been through the musical wringer as an organist who was faced with the task of conducting an orchestra for the first time – and eventually having come through safely on the other side – may I offer a few (hopefully) helpful hints for those who are about to jump over that challenging hurdle.

1. AN ORCHESTRA IS NOT A CHOIR

Conducting an orchestra is wholly different from conducting a choir. Instrumentalists know what they are doing, they don’t have to be told to play right notes. Therefore the conductor has to do a lot of preparation before he, or she, stands in front of the musicians. You have to know all the notes better than they do – and you need to know how all the notes fit together. It’s called doing your homework!

2. LOOK AT THE MUSICIANS

The essence of conducting an orchestra (and also a choir) is to look at the musicians 90% of the time, and not to have your head stuck in the copy. In order to be able to do this, mark your score with those semi-adhesive labels (cut into smaller pieces). Mark in bold ink (of different colours – black for the choir, red for the brass, green for the woodwind, blue for the strings …) when instruments have to be ‘brought it’ – you’ll need to glance at those players a couple of bars before they enter – mark when there’s a change of dynamics – mark when the choir or the soloists should start to sing … and so on.

3. GLANCE AT YOUR SCORE

In other words, so mark your copy that you can see at a glance what is coming up so that you don’t have to read the music. Continuous creative eye contact with your musicians is essential if they are to play and sing as you would wish them to.

4. PRACTISE CONDUCTING ...

And when you’ve marked your copy, practise conducting the music in front of a mirror. Notice how often you are looking at yourself, and how often you are looking at the copy. Are you reaching that necessary target of 90%? Are you making helpful gestures to bring in the trumpets on your right and the tympani on your left?

If you’re right handed, hold your baton in that hand and conduct very clear beats – 3-time or 4-time, or whatever. The left hand shouldn’t be a mirror copy of the right hand, (as so many conductors do!) but should indicate when instruments should come in, or when there is a change of dynamics. (And of course it’s all vice versa if you’re left handed.) Your hands need to be independent. This also needs practising.

5. ...WITH RECORDING

When practising conducting it’s jolly helpful to play a recording of the work you are about to direct.

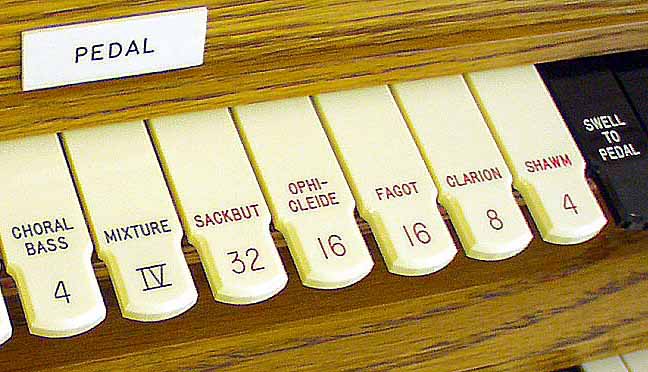

Why should you practise conducting? Well, why should an organist practise his voluntaries? Surely, to be able to play the right notes at the right time and, above all, to make music. So a conductor, in a not dissimilar way, ‘plays the orchestra’. He, or she, needs to know which notes are coming next – how they will be registered (i.e. which instruments are playing that passage) and, above all, to make music. This takes a lot of practice, and if the conductor is not willing to do it, disaster could follow. (See later!)

6. NITTY GRITTY ESSENTIALS

No doubt you will have someone who has taken care of all the practical matters of arranging chairs, providing a room (with a lock) in which musicians can place their instruments, supplying music stands and having sufficient light so that players can easily see their music.

What about refreshments for the orchestra and glasses of water for the soloists? Are they ready to hand? It’s vital to have someone other than you to take care of all these non musical details.

7. AMATEURS & PROFESSIONALS

Conducting an amateur orchestra is different from conducting a professional one. With amateurs, one occasionally has to amend the balance between instrumentalists and even, sometimes, to rehearse individual sections if there are problems with intonation or accuracy.

But professional orchestras will play all the right notes for you all the time. All you have to do (and it’s a big ‘all’) is to show that you know the music as well as, or better than, they do! And they’ll sense if you do, or if you don’t, within the first two seconds of your initial beat!

8. IF THIS IS YOUR FIRST TIME…

… say to them all at your rehearsal, after having welcomed them, that as this is the first time you have conducted an orchestra you will be relying upon their professionalism to enable the concert to be a success.

If you are big enough to admit your inexperience, you’ll find that your professional orchestra will give you a first-class performance, for you are saying, in effect, they know what they are doing, and I’m here only to start you off, and to bring in my choir when they need to sing.

When I was very new to all this, 50 years ago, I was conducting a performance of Bach’s St. John Passion. We came to a solo aria that I really hadn’t sufficiently prepared beforehand (!) and I couldn’t think how it should sound. But, having told the musicians that this was my first time, the instrumentalists quickly saw my look of helplessness and began playing without me, for they did know how it should sound. I was very grateful!

But if you try to brazen it out when you rehearse them they’ll know full well that you’re putting on an act and, whilst they’ll still play the right notes for you, they won’t necessarily be as helpful as you would wish.

9. ETIQUETTE

(i) In all things you should defer to the leader (or 'concert-master') of the orchestra. If there’s a musical problem in the rehearsal, ask the leader how it could be solved. Make a point of knowing the leader’s name for, when you welcome the orchestra at your rehearsal, knowing his or her name will immediately create enormous goodwill from the other players.

(ii) A professional orchestra will have a manager, who will tell you that, after so long, they will need a 5-minute break, and that the rehearsal is timed for 3 hours. At the end of those three hours the rehearsal must stop, for you can’t ask professionals to ‘give me five more minutes, please’. They’re not there because they like you, they’re there because they’re being paid! Being nice is not in their contract.

(iii) If you are conducting a work which is in sections, you should consider timing the rehearsing of those sections so that folk are not sitting doing nothing for long periods. Solo arias should be rehearsed towards the end of a rehearsal and the choir music should be rehearsed first, so that they can leave early before the other music is being rehearsed.

In other words, there’s a lot of preparation to do before your dress rehearsal which has nothing to do with learning the score! Do you have someone on your committee who could work with you for these practical matters? Two heads are better than one, and three heads are better still.

(iv) When rehearsing your soloists, defer to their wishes, for they will have prepared their music meticulously and will need you to lead the orchestral accompaniments at the tempi they prefer.

Have them stand where you can see each other. They will know when they have to begin singing, so there’s no need to ‘bring them in’ – but, on the other hand, it’s helpful to glance at them just before each entry. That will show that you and they are in musical accord.

(v) It would be even more helpful if you could run through their solos before the final rehearsal – with you playing the piano, if possible. That way you will all be able to perform more confidently.

(vi) You’ll know about the etiquette of ‘coming on stage’? This is pretty basic, but it’s worth mentioning in case you haven’t done it.

The choir should be already seated – they’ll need to practise getting to their seats in order – so have a singer sergeant-major available to organise their lining up and their sitting down together. (By the way, the choir should stand when you and the soloists come on stage. Your sergeant major should take care of that, too.)

The leader comes on stage half a minute before you, and takes a bow.

Then the soloists, followed by you, come on together – and take a bow . You could shake hands with the leader to show that it is the orchestra which will do the playing, not you!

(vii) And just before you begin to conduct at the concert, look at your choir, and look at your orchestra with an expression that says, ‘We’ve rehearsed this for months so that I know, and you know, that this will be a terrific performance. So let’s do it!!’ Such a look of confidence-building will set the right mood for your whole concert.

(viii) At the end of the concert, indicate that the soloists should take their bow first, then shake the hand of the leader (which indicates a public ‘thank-you’ to the whole orchestra). Then indicate that the applause includes your choir, and finally ask your orchestra to stand for the applause – which is when you take your bow – for in bowing, you are acknowledging the performance of all your musicians, for it is they who have created the music, not you – and so you're not saying ‘how clever I was!’

10. FINALLY

If you haven’t conducted an orchestra before and, at your first rehearsal, you give your down beat firmly, you’ll find that they won’t come in with you – they’ll play half a second after your beat.

Now, this is crunch time! If you have rehearsed your choir to sing with your beat instead of after it, it’s essential that your orchestra does the same. Therefore say to the orchestra, immediately, that as the choir sings with your beat, you’d be grateful if the orchestra would ‘play with my beat, please’. And then have another go. But don’t conduct more vigorously to try to ensure that this will happen. It is they who have to change, not you.

And if it’s still not right, say, ‘No, please play precisely with my beat, not after it.’ This will indicate to the orchestra that you really do mean what you say, and they will sit up straighter for you and respect you more. But, again, don’t conduct more vigorously – and never get cross! Always be courteous in everything you do – for that will create a tremendous atmosphere of goodwill from everyone and you’ll all eventually enjoy a terrific concert!

PS: The next day it would be very gracious if you were to write letters of thanks to your soloists, to the leader or manager of the orchestra and to the chairman of your choir. Very few folk do this; a thank-you costs nothing, but it means everything.

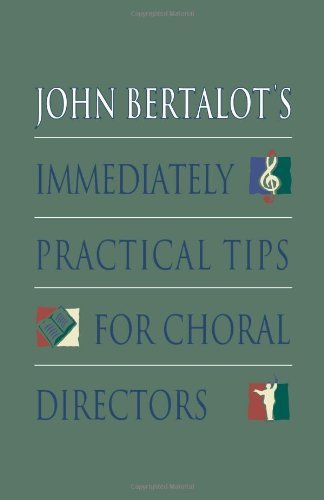

For more helpful information about training choirs and conducting orchestras,

see Dr. Bertalot’s second book on choir-training:

Immediately Practical Tips for Choral Directors

available on Amazon and ebayI