How to transform your choir

and fill your stalls

with enthusiastic singers

29 Major Musical Influences in my life No. 2

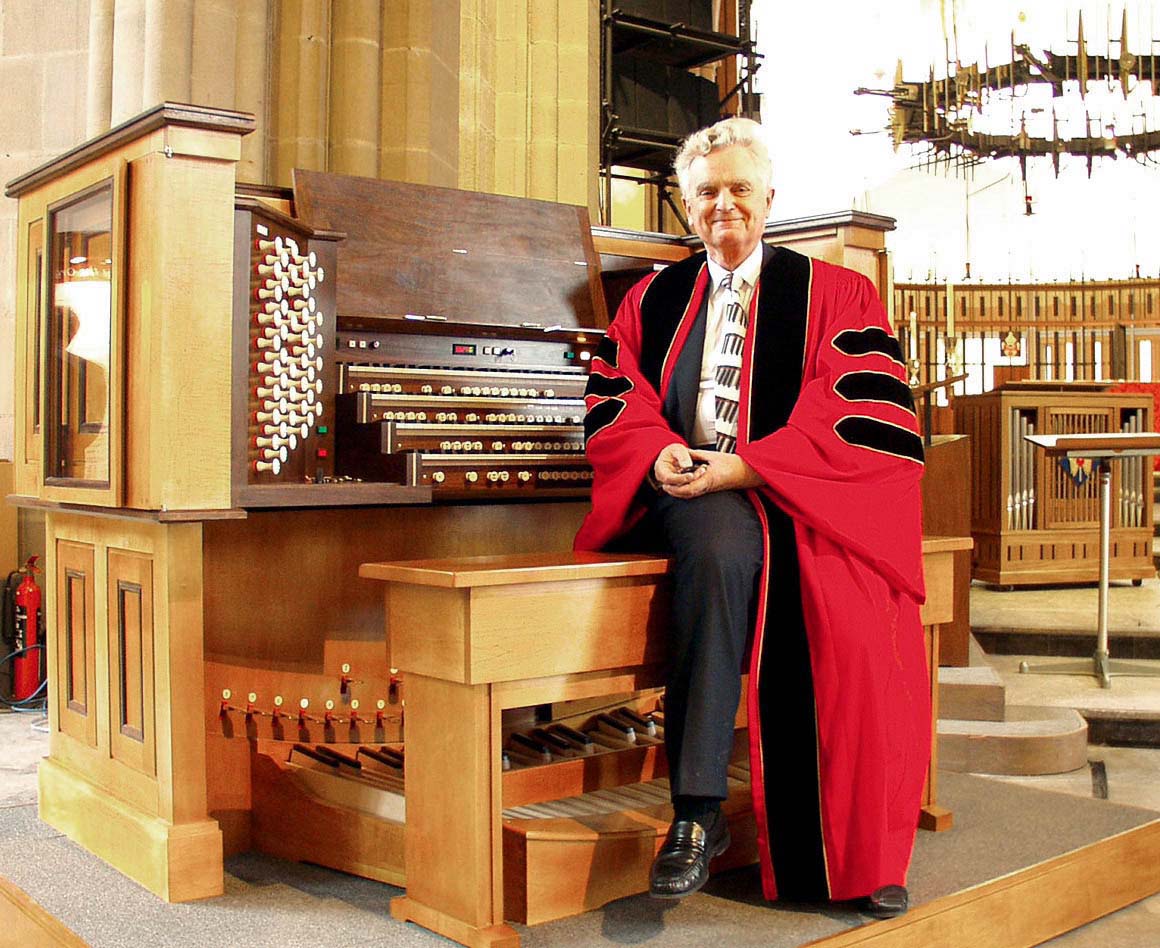

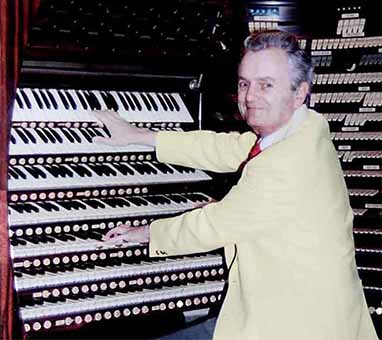

by Dr John Bertalot

Organist Emeritus, St Matthew's Church, Northampton

Cathedral Organist Emeritus, Blackburn Cathedral

Director of Music Emeritus, Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, USA

Here are some more invaluable lessons I have learnt from outstanding musicians which have transformed my life as a choirmaster. May they help you as much as they have helped (and continue to help) me.

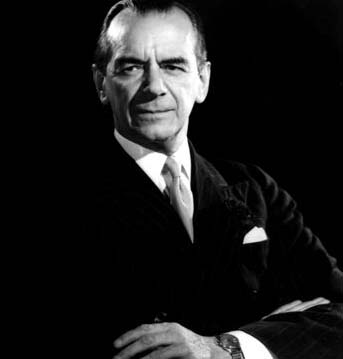

Dr. Boris Ord

Boris, with whom I studied for two years at Cambridge, was the legendary Director of Music of King’s College. He had two separate and distinct ways of conducting his fabulous choir.

1 He didn’t conduct them at all – he gave the responsibility to two senior choral scholars (undergraduates); one put his hands on the music desk and gave a continual beat with his two index fingers, and the other, on the opposite side, did the same whilst watching his colleague like a hawk. Every singer watched these two young men with equal concentration and the result was singing of the very highest unanimity and commitment.

2 When there was a particularly demanding anthem, Boris came down from the organ loft, stood next to the head boy and conducted in a similar manner with his two forefingers, looking intently at the senior choral scholar opposite, who took the beat from him.

Question: How could such minimal conducting have produced such outstanding performances?

Answer: Because Dr. Ord had a towering personality which infused every singer with the strongest desire to do his very best at all times. I’ve mentioned in previous articles that a choir is a faithful replica of its choirmaster. This is true for all of us.

But not all choirmasters have Boris’s dominating personality. However, all of us can learn to do what Boris did, which was to know the music so well that he didn’t have to look at his copy – he could look at his singers all the time: it was his eyes which commanded their attention.

I am constantly amazed, when visiting other cathedrals, to discover that some distinguished directors of music look at their copies to conduct even the simplest music, such as the Responses. I’ve even seen some brethren look at the music to conduct Amens! (And the trouble is that they have no idea that they are doing this!) If Simon Rattle can conduct Beethoven’s 9th Symphony from memory – if Daniel Barenboim can conduct Elgar’s cello concerto from memory, surely even the most inexperienced choirmaster could conduct the simplest anthem from memory. But I’ve not seen any church or cathedral musician do this!

Why should we conduct from memory?

Answer: to inspire our singers with our own musical interpretation – for a performance needs to be more than just a reproduction of what we achieved in rehearsal. There must be a ‘sense of occasion’ to give every performance that extra shine and thrill.

But what about Dr. Ord not conducting his choir for the less demanding music? Didn’t he care about such bread-and-butter music? Of course he did, but he knew that, when he gave the responsibility to his choir to sing on their own, with their two senior singers acting as conductors, they would accept that responsibility and rise to that challenge by becoming a self-disciplined body.

You may think, ‘That’s OK for King’s choir, but not for mine.’ Oh yes it is!

In retirement I've been organist of a village church with an adult choir largely made up of grandparents. (The other singers, apart from two, are great-grandparents!) I have given the responsibility to one singer on each side to indicate during services when they should stand up and when they should sit down – this immediately gives them a sense of corporate self-discipline. (We also practise this during our rehearsals to reinforce the ‘in-house’ leadership.)

During services, for the last chord of hymns or anthems, I watch the leader who gives an imperceptible nod to the singer on the other side when that final chord should end, and I bring off the organ chord with the choir. In other words, I have made my choir into a self-disciplined body of singers which takes responsibility for their own singing. If I can do this with my village church choir you can certainly do it with yours.

Why should you? Because by exercising self-discipline they give a better performance – and that’s what all choirmasters want.

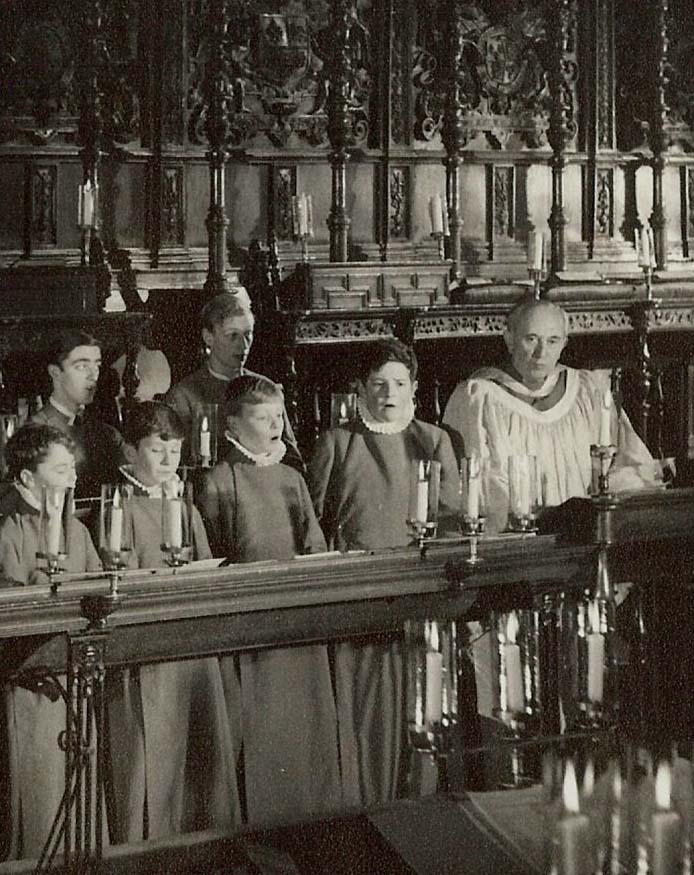

Last year I was invited to conduct the choirs of Trinity Episcopal Church, Princeton, NJ, where I had been Director of Music for 16 years before my retirement. I asked the new Director of Music to take some informal photos during my rehearsal in that church where I had spent 16 most happy and fruitful years. We were about to rehearse Tippett’s ‘Steal away’.

You will notice in this un-posed photo that I am looking at the whole choir, and every singer is looking at me. We were making creative contact, and everyone knew it, so that we could sing as a unified, disciplined body, absolutely together.

‘Look’ is one of the most actively creative four-letter words for choirmasters and for their choirs.

Sir Malcolm Sargent…

…was an English charismatic orchestral and choral conductor during the middle of the 20th Century. His abounding musicianship permeated everything he conducted; he was highly intelligent and he also had a lovely speaking voice which was often heard on the BBC.

During my six years as Organist of St. Matthew’s Church, Northampton, my Northampton Bach Choir gave regular performances of major oratorios. One year we performed Honegger’s ‘King David’, which calls for a large orchestra, chorus, soloists and narrator. As was the custom in those days we hired the orchestral parts and score, which arrived one month before the performance. When I opened the enormous score I saw that someone had covered it with markings in coloured crayon. ‘Oh dear,’ I thought, ‘I’ll have to clean this up before I can begin to learn the score.’

But I glanced at the title page and saw that, written in a flowing hand in blue crayon, were the initials MS. ‘Malcolm Sargent!’ I thought, ‘these are his markings; I’d better look at them more carefully.’ I quickly discovered that Sir Malcolm had marked every important entry which a conductor needed to notice, and that every group of instrumentalists or singers was marked in a different colour – red, blue, green, black, brown … so that the conductor could tell at a glance who would be coming in next. He could see, for example, that he should bring in the trumpets in two bars’ time, and that the next choir entry was loud. This was an object lesson in how to mark a score.

Sir Malcolm, towards the end of his life, didn’t have very good eyesight but he wouldn’t wear glasses. This was in the days before contact lenses, so he needed to mark his score so that he could see at a glance, from fully four feet away, what was going to happen next. Therefore he was able to look at his musicians most of the time, whilst only glancing at his score.

Ever since then I, too, have marked my scores so that I can see, at a glance, what is coming next and who needs to be ‘brought in’. And having been a cathedral Director of Music with many complicated services to lead, such as ordinations, I have also marked my orders of service, so that I know when I should conduct the choir, or play the organ, or whatever.

Too many conductors read their scores – for they haven’t marked them – and so they only glance at their singers. That’s the wrong way round. LOOK at your singers, GLANCE at your score. They haven’t done their homework. Doing your homework is vital if you are to fulfil your vocation.

Fernando Germani…

… was one of the outstanding organ virtuosos of the 20th Century. He stayed in my home twice when he gave recitals in Northampton, and gave me an unforgettable organ lesson which lasted for several hours.

But it was because of what he played in his second recital that I remember him most. His major work was Liszt’s ‘Ad nos ad salutarem undam’, which lasts some 25 minutes and ends with an exciting fugue. Whenever I had heard other organists play this demanding piece I had ‘endured’ the first half, some of which was in Liszt’s most introspective mood, in order to exult in the thrilling fugue. But when Germani played it I found his whole performance compelling.

When we reached home I asked him how he had communicated the message of every note so clearly to me. He said, ‘It’s based on a chorale from Meyerbeer’s Opera, Le Prophète.’ ‘Oh yes,’ I answered, waiting for lightning to strike.

His next sentence altered my whole approach to preparing and performing music. He said, ‘Before I learnt Liszt’s organ piece I learnt Meyerbeer’s opera!’ (Take 5 seconds’ silence to realize what Germani had said!) Germani went to the source of Liszt’s inspiration and therefore knew exactly what Liszt was saying in his music. I’ve never forgotten that blinding light which struck me when Germani said those words. So now, before I conduct a choral work, or play an organ piece, I find out as much as I can about the composer and why he wrote that work.

In church and concert hall it’s the words which inspire the music we sing. Do you know what the words mean of the music you conduct? Does your choir know what the message of those words is? Do you know to whom Luther refers in the last line of the first verse of ‘A mighty fortress is our God?’ (‘… on earth is not his equal.’) Is it God? No, it’s not!

And so, when you’re rehearsing your choir in an anthem or a hymn, ask them what the words mean. You may be met by a stony silence!

And as Germani implied, understanding the words, which may also be the source of the inspiration for an organ piece, is essential if we are to perform it intelligently. I recently saw on TV a distinguished organist perform Bach’s Partita, ‘O Gott, du frommer Gott’. This is a set of variations on a chorale melody. The recitalist played well but the ‘message’ of each variation was not there. Why? Because he didn’t know that each variation was based on a verse of the hymn, and that Bach was interpreting the message of the first verse in the first variation, the second in the second, and so on.

The whole hymn is about one’s Christian vocation, from early age to death, and beyond the grave to heaven. For example, the 7th verse describes old age. I play this movement on quiet 16 & 8ft reeds, slightly unevenly, to give an arthritic feel! The last movement is about life after death – trumpet calls echo from side to side, and then God reaches down his hand to lead the Christian tenderly to heaven. These changes of mood are clearly portrayed in Bach’s music, but none of them came through in that recitalist’s performance. All Bach’s chorale preludes are based on liturgical words or Lutheran hymns. These were at the centre of his Christian life, and it shows in all his music.

Some organists don’t even look at the verses which inspired Howells’ Psalm Preludes or Reubke’s 94th Psalm! How much homework do you do when you prepare voluntaries, or when you prepare music for your choir to sing?

Thomas L. Duerden

TLD was my predecessor as organist of Blackburn Cathedral – a post he held for 25 years. He was a gifted choirtrainer – his choir won first place at the Welsh National Eisteddfod for several years and his former choristers, some of whom are still with us, revere his memory. He was a great disciplinarian and cared deeply for all his choristers, boys and men alike.

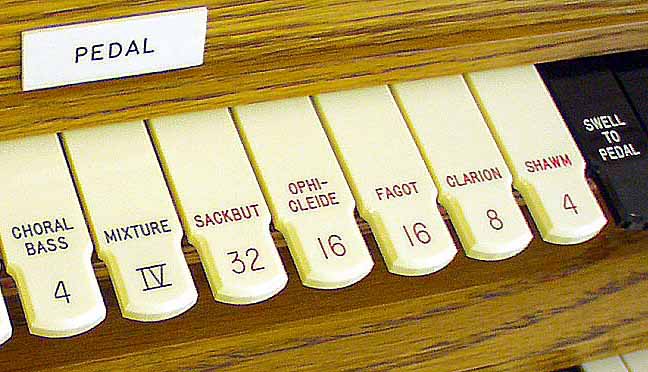

When I succeeded him in 1964 the cathedral was in transition – it was about to be transformed from a blackened building whose roof leaked, into an airy, well-lighted cathedral whose ceilings were painted in rich medieval colours. It was also to have a new organ which, today, ranks as one of the finest cathedral organs in this country.

But it was TLD’s sense of discipline from which I learned so much. The boys sat with their arms folded whilst lessons were being read and sermons preached. I didn’t know that boys could sit still like that, and so I endeavored to maintain that tradition.

However my approach was to change from an imposed discipline to a willing self-discipline.

When a new boy joined the choir he was given a number of singing tests to pass (this has now been expanded into the RSCM’s Voice for Life). And when he had completed these tests he was given a cassock and the head boy showed him how to process into the cathedral in his new cassock, bow to the altar and then sit absolutely still in the choirstalls for five minutes on his own with his arms folded, before the head boy told him that he should now process back to the vestry with equal dignity. When he had done this to the head boy’s satisfaction, he qualified to become a member of the cathedral choir. And he was thrilled!

One former chorister told me recently that his attendance under TLD was 100% because he was afraid to stay away; but when I was in charge his attendance was 100% because he wanted to come!

And so I have always encouraged my singers – boys, girls and adults – to foster a sense of self-discipline in attendance, in demeanour and in their singing. This worked at the cathedral, it worked for my choirs in the USA and it continued to work in my little village church. I’ve written about this in previous articles, but it was through TLD that the inspiration came.

Anon

‘When you set a boundary for a child he, or she, will immediately cross it – to see if there’s a boundary there.’

Daniel Chorzempa…

…is a musician of international standing. Many years ago when we were both in our late 30s, he gave a recital in Blackburn Cathedral which I’ve never forgotten. Blackburn Cathedral has a reverberation of 6 or 7 seconds, and so it is very difficult for audiences to hear the notes clearly. However, when Daniel played I could hear every semiquaver with crystal clarity. I watched his fingers closely, but couldn’t see how he achieved this. When we returned home I asked him how we could hear every note – and he gave me a devastating two-word answer: ‘I listen!’

If you’re an organist playing a piece with a solo reed, do you realize that when you take your hands off the manuals together, the sound of the solo reed continues for a fraction of a second, and then ends with a ‘click’? If you really listen, you would hear this, and so you will cut slightly short the last note of the solo.

Do you really listen to the sound your choir is making – or have you got so used to it that you don’t hear that the tenors are too loud, that the altos are singing slightly flat, and that all the singers come in after the first beat? ‘Listen’ is another creative word for choirmasters and choirs – and it was Daniel who impressed this on me.

Dr. Christopher Robinson …

…has had a dazzling career as a cathedral musician, occupying some of the most prestigious posts in this country.

When I was living in the USA I attended one of his choral workshops at St. Thomas’ Church, New York City.

He was leading the boys’ rehearsal and conducting very gently. In one anthem the boys didn’t come in when they should have done, so he stopped and asked them, ‘Who is singing, you or me?’ ‘We are, sir,’ came the answer. ‘Do you know when you should come in?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Let’s try it again.’ And he played the introduction on the piano and indicated, still very gently, when the boys should sing their first note – and they did. Why? Because Dr. Robinson had given the responsibility to them to come in on time. They were not waiting for him to bring them in with a strong gesture.

This is a fault I see in so many illustrious choirs today; their conductors think it is their responsibility to make sure that their choirs start together (which, in a way, of course, it is), but the ultimate responsibility is for the individual singers actually to do it when they know they should. But when conductors flail the air in their efforts to bring their choir in, the singers think, ‘If he wants to kill himself by conducting so energetically, let him! It makes no difference to us.’

Accepting responsibility for one’s own singing works not only for cathedral choirs (alas, not all of them do this!) but it also worked for my village church choir. When they sing Jesu, joy or any other anthem, I rehearse them in taking personal responsibility for coming in exactly on the beat, and not after it. And it works. It’ll work for you, too!

© John Bertalot, Blackburn 2013